It’s funny, but Shakespeare is teaching me Italian stories

It’s curious to find the heart of Italy in the soul of England, but so it is. For Shakespeare put it there. For years now, I’ve been hunting down Italian stories, and the last thing I expected was that Shakespeare would give me the breakthrough I was looking for. The most desperate loves, the vilest deceptions, the most delightful cross-dressing dalliances and the bitterest revenge. Shakespeare found them in Italian novellas and adapted them to the London stage.

I have to admit, although the journey has been fun, it’s not so easy to plunge into the ocean of Italian literature, not knowing where it might take you or in which direction to head. Every exploration always brought something new to light, but still something seemed elusive. It didn’t make sense to me the way English literature makes sense. Something seemed missing. Where were the ripping yarns? (Credit: Palin and Jones).

Of course, that is all very subjective, and has got everything to do with the fact that I grew up in Australia. Despite some wonderful teachers growing up, there were simply no mentors I was lucky enough to meet who might have introduced Italian literature and Italian stories. So for me, Italian literature was like a great puzzle. A huge box of treasures that you poured out on the table, not sure where one piece fits with another.

Yet, slowly bits and pieces began to fall into place. There are lots of books that claim to tell you the story of Italian literature. But like other great ‘national’ literatures, the national myth-making can hide as much as it reveals. Until recently, for example, you might struggle to find a single woman named among the ‘canonical’ figures of Italian literature, despite the fact that they are there and they are astonishingly important not just to Italy but as heralds of modernity.

What was I missing? I would ask myself this, even as I gradually mapped out the vast landscape of Italian stories (literature). The obvious place to start was Alessandro Manzoni’s The Betrothed, a delightful read, and Italy’s first modern novel; but truth be told, Manzoni modelled his book not on Italian stories, but on the romantic English novelists of the generation before him. We do owe a debt to Manzoni, for he rescued Italian from a formalism which had near strangled the language, but there wasn’t a clear path from him back to his Italian predecessors.

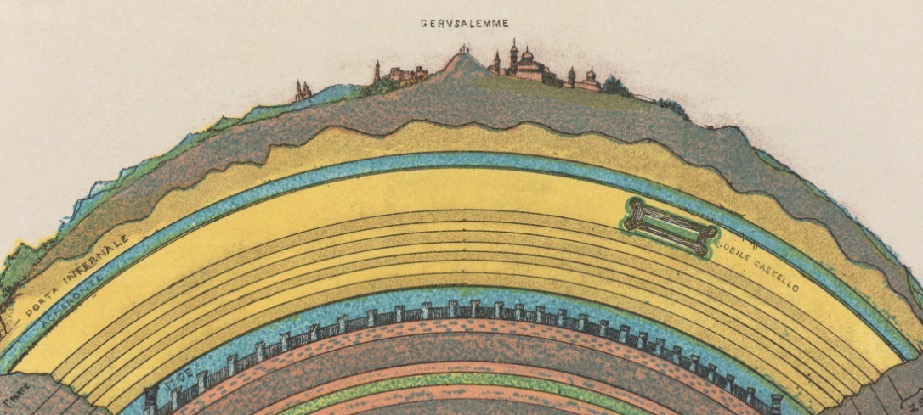

Dante’s poetry was a must, and great fun to explore. He is historian, satirist, political commentator and philosopher all rolled into one. He gave us the language, showed us how to use it, and has some great love poetry to boot. A couple of years ago now, the Dante Alighieri Societies of Australia hosted a national series of seminars about him. Many of the talks are now recorded in a book.

I have yet to give decent attention to Boccaccio, another important ‘founder’ of Italian writing, but more about him below. Italian fairy tales are fun to explore, and there are some great Italian collections. They give us a sense of what children heard late at night.

Discovering some of Italy’s female writers and poets of past centuries smashes preconceptions that might be held about gender relations in Italy (or its feminist might have been). Those female writers are still under appreciated, e.g. Laura Terracina who took up the feminist bent of Ludovico Ariosto and put it on steroids.

The “verismo” writers of the nineteenth century provide a gritty introduction to the harshness of life in that era. I’d even set out to translate “Il Drago” in a series of articles, that didn’t get enough attention from me, and ended up stretching out over years. Last year, I decided to get the project finished, and I’m glad I did. I found it wasn’t as hard as I’d feared and it’s now a published short story under the title “The Old Dragon: Il Drago by Luigi Capuana”.

There is so much more of course (not least 20th and 21st century literature). They’re on the bucket list. But still it felt like there was something profound: a vast gap in the canvas, that I couldn’t fill.

Shakespeare to the rescue

A couple of years back, I discovered that Shakespeare (and other English writers of his generation) were greatly influenced by stories that came out of Italy. Good historians of English literature know it; but as in Italy’s case, some parts of the story are put up in lights and other things are, well, barely mentioned in polite company. Very interesting and surprising, I thought, and maybe it could be the subject of a couple of great articles, but that too languished in the “work on it later” drawer, until recently.

If you’ve read my article on Shakespeare in Love, you’ll know that re-watching the movie motivated me to really look at what was going on. Shakespeare not only loved Italian stories, he hunted them down and put them on stage.

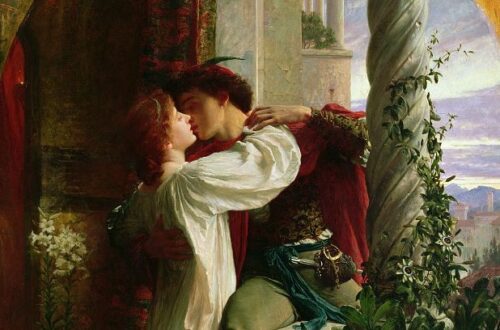

If history was written in a more even hand, names like Matteo Bandello and Cinthio would be as well known to us as Shakespeare. For Bandello’s version of Romeo and Juliet inspired Shakespeare and it is beautiful in its own right. The major plot line of Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing is also taken from Bandello. Othello was drawn by Shakespeare from one of Cinthio’s novellas, as was Measure for Measure, and there are other examples. And while Shakespeare deserves credit; for he often takes these stories to another level and has made them immortal, the Italian originals are so profoundly written into his plays, that Shakespeare cannot be regarded as the only author. He is a masterful adapter of such stories for the stage.

So what was I seeing? Where did all the novellas go? Why was Matteo Bandello’s novella about Romeo and Juliet so loved that it was translated across Europe and put on stage in England in his own era; and yet we have even forgotten that once upon a time, novellas were all the rage in Italy?

Here was the missing piece. This was where the Italian stories had been hiding; still waiting to be explored.

Novellas are form of literature that’s not familiar to us today. We of course love novels. These are typically much longer stories that we might read over a few day, weeks or even months. Novellas are somewhere between short stories and novels in length and they can be read in a single night. They make much more sense, when we remember that the TV and mass entertainment simply wasn’t available in the past. A novella could be read (and was most likely read out loud to a gathering) in a single evening and provided a great way to pass the time in company.

In fact, we see this very model written into the novellas themselves. Writers like Bandello would introduce their stories (sometimes pretend) that they had heard the story from so and so one evening or afternoon at some eminent person’s residence. Boccaccio also in his Decameron, used this form of literature. He too structures his novellas around people sharing stories with each other for entertainment. Italian writers loved the model, and it was widely copied by those that followed Boccaccio. In Boccaccio’s case he used the ‘storytelling’ trope as a “frame story” – a model found in many cultures – for example in the Thousand and One Nights, in which Scheherazade tells a story every night to a mad prince.

Shakespeare loved novellas too. He mined Italian novellas for material to put on stage. This becomes more obvious when we think about how many of his plays are set in Italy. And, if you are looking for a place to start to come to grips with Italian literature, you could do a lot worse than starting with those Italian stories that Shakespeare has made world famous. He chose some of the best.

Some of the questions about Shakespeare that come up repeatedly, involve whether and how much time he might have spent in Italy and the extent to which he might have known Italian. Such arguments are difficult to resolve without giving careful attention to the raw materials he had available in England (whether in translation or in the original). But even more fun than that, is just appreciating the Italian stories he drew on for the great material that Shakespeare knew they were. So yes, Shakespeare, is teaching me about Italian stories. He has inspired me to work on translating some of them into English (a work in progress).

Images

Bust of Shakespeare in Verona at the mythical tomb of Juliet. Sailko, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons