Dante Alighieri Citizen of the World

Dante Alighieri says it plain: “to me, the world is one native country, like the sea is to fish“. Dante sees himself as a “citizen of the world”. He is, admittedly, a poet who is internationally celebrated. Nonetheless, we can find the discovery stunning. Dante is so closely paired with the Italian “brand”, that his observation seems out of place. It is natural to assume Dante would be concerned, in some sense, with the Italian national project. He is after all widely known as the “Father of Italian”. Yet it is not the case.

Our tendency to assume that the past was much like the world today, is the nub of the problem. For Dante was not born in “Italy”. For another 600 years no such country would exist, nor even, in Dante’s time, be seriously dreamt of. Dante’s “country” was the Republic of Florence. His native city exiled him never to return. Yet Dante never needed to leave the peninsula of Italy, for most of it was not his country of birth.

Lest we might assume Dante didn’t care about his native city, he addresses the question. He tells us that he has been a patriot to his native city and paid dearly for it:

“… I drank from the Arno before cutting my teeth, and love Florence so much that, because I loved her, I suffer exile unjustly …”

De Vulgari Eloquentia, translated by Stephen Botterill

His is a “patriot and cosmopolitan” at the same time. He is someone who loves both his country and the world, and sees no contradiction between the two.

In further explanation of his attitude, he cides narrow-minded assumptions which vaunt our own national culture above those of others. When he considers the world as a whole, reason rather than sentiment, compels him to “firmly maintain”:

… that there are many regions and cities more noble and more delightful than Tuscany and Florence, where I was born and of which I am a citizen, and many nations and peoples who speak a more elegant and practical language than do the Italians …

De Vulgari Eloquentia, translated by Stephen Botterill

Again, we may be surprised that these are Dante’s words. That we are says more about the ongoing re-invention of Dante down the centuries, than it does about Dante himself. He was both lauded and condemned by his contemporaries. Neither their opinions nor that of latter generations impeded him from his astonishing project of laying the foundations of the more “eloquent” Italian language we know today. Nor, notably, did Dante limit his poetry in that eloquent language to the physical world. His greatest work is most concerned with the inner life of the soul: a universal topic which transcending earthly things.

Notes

The translation at the beginning of this article comes from de vulgari eloquentia. In Latin Dante writes: “Nos autem, cui mundus est patria velut piscibus equor“. My translation varies slightly from Stephen Botterill’s, as it seems to me to obscure the clarity of Dante’s language. Stephen Botterill’s translation reads: “To me, however, the whole world is a homeland, like the sea to fish”. The word patria can be translated as “homeland” or “native country” or “my country”. It is, of course, the Latin root of the English word “patriot”.

Bruno Migliorini devotes the fifth chapter of his seminal work The Italian Language, to Dante. The chapter appears between chapters on the “1200s” and “1300s”) Dante is so influential a figure. Migliorini notes Dante’s fame as “Father of Italian”.

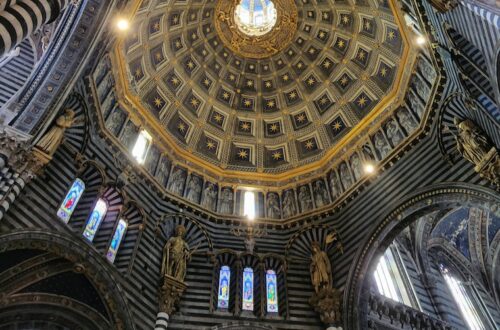

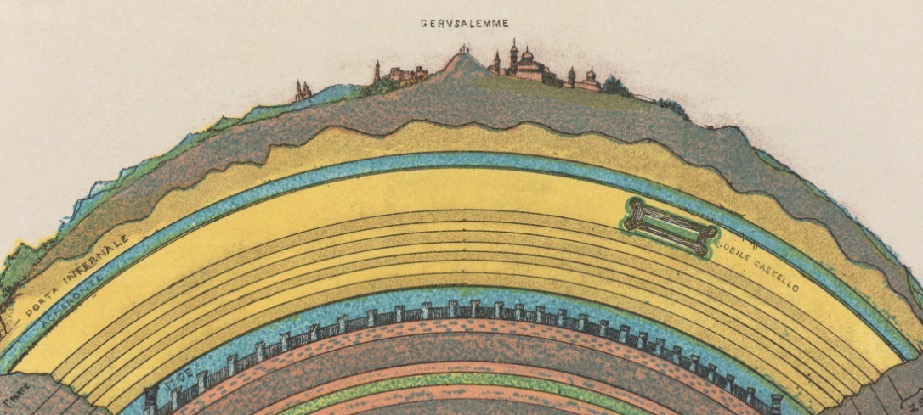

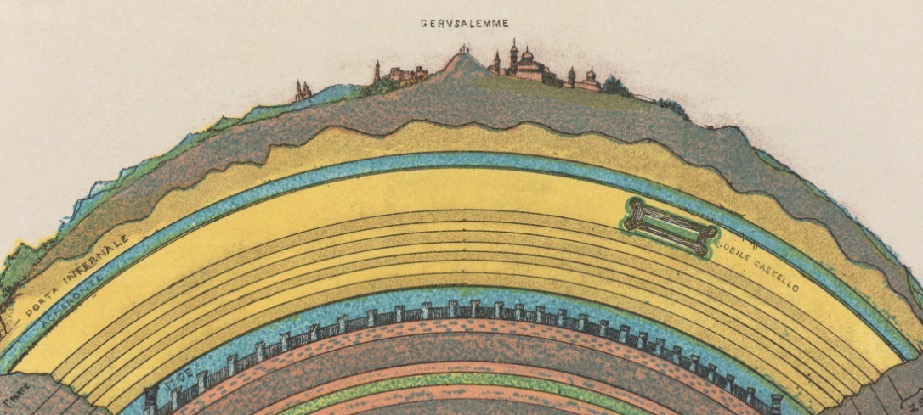

Image

A section of Michelangelo Caetani “Cross Section of Hell” based on Dante’s Divine Comedy