Isabella’s Castle Prison and Her Poetic Escape

Isabella di Morra looked out from a height. Below, in a deep chasm, flowed a river. Her river, the Sinni. Isabella turned her eyes to the sea, searching the horizon for a ship. It was the ship that would carry her free from her prison, her own family’s castle.

D'un alto monte, onde si scorge il mare,

miro sovente io, tua figlia Isabella,

s'alcun legno spalmato in quello appare,

che di te, padre, e mi doni novella, ...

From a high mountain, where sea is seen,

Often I gaze, Isabella, your daughter,

For the gleam of any glistening beam,

Which of you, father, brings news across water ...

Ch’io non veggo nel mar remo né vela

(così deserto è lo infelice lito)

che l’onde fenda o che la gonfi il vento.

But no oar which parts the bitter deep,

Nor wind filled billowing sail, do I see

(so empty and mournful the shore's sweep)

Yet her father’s ship never came. For Isabella di Morra it was fated so. Her father, the Baron of Favale, wagered badly in war. And war swept him far away to France never to return.

I cari pegni del mio padre amato

piangon intorno. Ai! Ai! miserabile fato.

mangiare il frutto, c'altri colse, amaro

quei che non mai peccaro, ...

The bitter pains of my beloved father

Weep about me. Ai! Ai! Miserable fate,

Eating the bitter fruit, which others gather,

For those who have lived in sinless state ...

Isabella di Morra’s Confinement

Isabella was imprisoned far from any company that might fill her life with joy and richness. She had been schooled in the language of the poets and it made of her a stranger in a strange land. For her brothers, who penned about her life, had no use for such things. Her pain she poured into verse.

Poscia che al bel desir troncate hai l’ale,

che nel mio cor sorgea, crudel Fortuna,

sì che d’ogni tuo ben vivo digiuna,

dirò con questo stil ruvido e frale

Since you have trimmed the wings of fair longing

rising in my heart, Cruel Fortune

With this frail and rough reed

I will speak of each of your bitter denyings

alcuna parte de l’interno male

causato sol da te fra questi dumi,

fra questi aspri costumi

di gente irrazional, priva d’ingegno,

Each part of the wrong entire

Willed only by you, among these briars

Among the bitter ways

Of thoughtless folk, deprived of higher nature

ove senza sostegno

son costretta a menare il viver mio,

qui posta da ciascuno in cieco oblio.

Where without support

In confinement, my life is squandered

Hidden from all, here, in blind forgetting

Isabella’s River

The river which flowed below her castle carried both her hopes and anguish.

Quanto pregiar ti puoi, Siri mio amato,

de la tua ricca e fortunata riva

e de la terra, che da te deriva

il nome, ch’al mio cor oggi è sì grato; ...

You can well rejoice, Siri my beloved,

Of your rich and blessed banks

And of the earth, from which comes your name

To which my heart today is thankful ...

***

Torbido Siri, del mio mal superbo,

or ch’io sento da presso il fin amaro,

fa’ tu noto il mio duolo al Padre caro,

se mai qui ’l torna il suo destino acerbo.

Murky Siri, so indifferent to my ills

Now that my bitter end approaches

Send word of my lament to Father dear

If he should ever return from his too soon cares

Her end came when her brothers discovered that she dared to impugn their “honour”. She had exchanged verses with a neighbouring noble. Her teacher fell first before their violence. For he had carried their messages. Then she herself was felled by their blows, beaten to death.

Still their bloodlust was not sated. For they hunted out the noble and him too, they did to death. It was only for the last crime that the arm of the law was finally raised against them.

Isabella’s Transcendent Vessel

Yet another part of Isabella di Morra’s story is inscribed in her verses. For she speaks of a transcendent gangway across which, perhaps, she boarded another ship, and escaped her prison.

Scrissi con stile amaro, aspro e dolente

un tempo, come sai, contra Fortuna,

sì che null’altra mai sotto la luna

di lei si dolse con voler più ardente.

There was a time, when as you know

With bitter and pained words I wrote against Fortune

As if no other under the lune

Had ever suffered more her blows

Or del suo cieco error l’alma si pente,

che in tai doti non scorge gloria alcuna.

e se de’ beni suoi vive digiuna.

spera arricchirsi in Dio chiara e lucente.

Now the soul of its blind error repents

In such doctrines there is no glory

And if of life's gifts it lives deprived

It hopes for fulfilment in God, pure and radiant

Né tempo o morte il bel tesoro eterno,

né predatrice e vïolenta mano

ce lo torrà davanti al Re del cielo.

Not time, nor death

Nor predator or violent hand

Will strip from us eternal heritage

Before the King of heaven

Ivi non nuoce già state né verno,

ché non si sente mai caldo né gielo.

Dunque ogni altro sperar, fratello, è vano.

There not summer nor winter pain

Not heat nor bitter cold is felt

Every other hope, my brother, is vain.

Isabella di Morra was more than victim. For her verses recall her life, and her murderous brothers, who would long have been forgotten, are now confined forever in the castle of condemnation which her words have fashioned.

Notes and Sources

This article tells the story of Isabella di Morra, and of course the verses are hers, for which I have provided my translation into English.

Isabella di Morra lived in the sixteenth century from around 1520 to 1546. She was murdered by three of her brothers. Her story reminds us that fairy tales such as Rapunzel (or Petrosinella in the older Neapolitan fairy tale), carry a darker truth.

By 1552, the small collection of Isabella’s poetry that has survived was published in Venice. In 1629, the story of her life was set down in the family annals by her nephew, Mercantonio di Morra. He was a son of a younger brother not involved in Isabella’s murder.

Like Laura Terracina, Isabella di Morra lived in a time of change. It was a time when some women saw a vision of an escape from age old violence and constraint. They used the written word to speak of what they saw and experienced. Their stories were largely forgotten and written out of the Renaissance. They have only begun to be restored from historical oblivion in recent decades.

Isabella lived in Valsinni Basilicata. The town and her family’s castle sits on a height above the Sinni (or Siri) river. The river flows into the Ionian Sea.

Irma B. Jaffe, Gernando Colombardo, Shining Eyes, Cruel Fortune: The Lives and Loves of Italian Renaissance Women Poets, Fordham University Press, 2002

Alma Forlani and Marta Savini, Scrittrici d’Italia: Le voce femminili più rappresentative della nostra letteratura raccolte in una straordinaria antologia di prose e di versi: dalle eroine e dalle sante dei primi secoli fino alle donne dei giorni nostri, Newton Compton, 1991

Juliana Schiesari Isabella di Morra (c. 1520 – 1545) in Rinaldina Russell (ed) Italian Women Writers A Bio-Bibliographical Sourcebook, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut 1994

Rhymes, Isabella di Morra, wikisource

Images

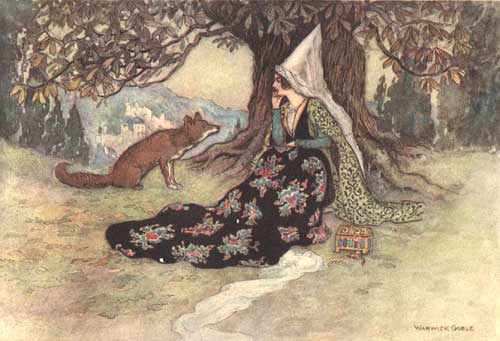

- An image reputed to be of Isabella di Morra

- The di Morra Castle, creative commons image Wikipedia

- The Sinni River at sunset, creative commons image Wikipedia

- A vessel of Isabella di Morra’s time

2 Comments

Michael Curtotti

Hi Alida, Thanks for the kind feedback. Isabella di Morra’s story is really striking, and absolutely still so relevant today. regards Michael

Alida Poeti

I was a lecturer in Italian studies for 43 years and I am ashamed to say I never included a poem of hers in any of the anthologies I compiled for students taking my History of Italian Literature modules, though I had come across her name a number of times.

I am glad that academics today are rediscovering and giving relief to poetry written by Italian over the centuries, almost always inspired by personal suffering, lose, constraint, injustices besides love and suppressed passion, but still very relevant to the plight of far too many women of today.

I read your piece with interest and liked your translation of Isabella’s verses.