Emperor Frederick II, the Wonder of the World and the Art of Falconry

Frederick II has been praised to the heavens and condemned to the depths of hell (by both Pope and Poet). The Son of Apulia, Wonder of the World, Holy Roman Emperor, perjurer and sacrilegious heretic, “Sultan” of Lucera, violator of his pledge as crusader, peaceful liberator of Jerusalem, enlightened patron of science and founder of universities, brutal in the extreme, law maker, the lamented sunset of the glory of Norman Italy. He has been called the first European and the “first modern man to sit on a throne”. He was also the author of “The Art of Falconry” or de Arte Venandi cum Avibus.

Such are some of the memories which come to us of a man who in his private moments contemplated not earthly conquest, but the nature of the flying creatures called birds. In such contemplation, he may have sought sanity (or as much as was possible for a medieval monarch in a brutal world).

Falconry was a pastime to which he was devoted, seeking to practice it as a high art (even, it is said, losing a battle as a result of spending too much time with his birds). When the Golden Horde was conquering Hungary and Central Europe and Batu Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan, sent Frederick II a message demanding his submission and ordering him to come and take up an office in the Khan’s court. Frederick is said to have joked that he would make a good falconer for the Khan, but he did not send him a reply.

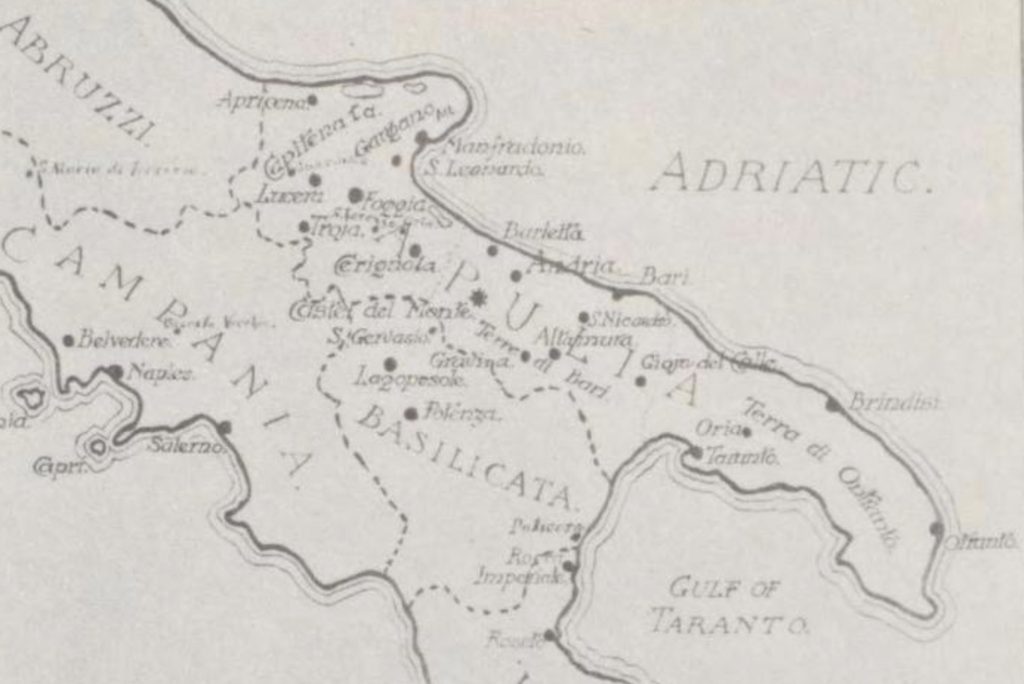

Of course his love of birds is not what Frederick is mainly remembered for. He is of course remembered as a Holy Roman Emperor. He was born in Ancona in 1194 of the union of two kingdoms which had previously been mortal enemies. Constance, his mother, was the daughter of Roger II of Sicily, the Sicilian Norman king who commissioned the most advanced map of the world yet made. On his father’s side, Frederick was a Hohenstaufen, a German dynasty which produced three Holy Roman Emperors including Frederick himself. His parents both died while Frederick was still a child and his mother, placed him in the care of the Pope.

His mother could not have made a better choice, but the political realities made it virtually inevitable that Pope and Emperor would become enemies, for it had been fixed Papal policy for centuries to prevent the encirclement of Rome by a single political authority. Yet this very thing was written into Frederick’s own being. Frederick rode the storm in his survival and rise to power, still emperor until his death in 1250. His life took him from his northern realms in Germany to Palestine where he also reigned as “King of Jerusalem”. His world was one in which neither allies nor subordinates could be trusted and his reign was a catalogue of battles and stratagems to defeat those who stood in his path or sought to threaten his authority.

Of the Art of Hunting with Birds: de Arte Venandi cum Avibus

Of the countless conquerors and sovereigns who have ascended the throne, a handful have been writers and most of those have written in praise their own deeds (we may take as exemplar Julius Ceasar’s Gallic Wars). Some have taken up the arts of government, or the conduct of war, or questions of philosophy or religion. Only Frederick II wrote a treatise on falconry and indeed what is in reality a scientific treatise on birds.

This curious artefact gives us an opportunity to reach beyond the second hand opinions of his cheer squad and detractors and (and least in translation) to read Frederick II’s own words. It is the case that much of what was written in the centuries after him in the Latin west is unreliable because of the partisanship around him. (For example, claims that he conducted live experiments on human beings are in this category).

Frederick II claims authorship in the preface:

Liber divi Augusti Frederici secundi Romanorum imperatoris Jerusalem et Sicilie regis de arte venandi cum avibus

Book of the Divine Augustus Frederick II Emperor of the Romans, King of Jerusalem and Sicily, The Art of Hunting with Birds

Wood and Fyfe Translation, The Art of Falconry …, p 4

Further, there is no doubt that Frederick is the author of de Arte Venandi cum Avibus – the Art of Hunting with Birds. He substantially wrote or dictated the work and as author Frederick II adopts a scientific method. He draws on Aristotle (as a primary source on natural history), and draws on existing works on falconry, including having translated into Latin important works on Falconry which were available in the Arabic language. Furthermore he draws on observation, making the point that where his own experience differs from Aristotle he will depart from the great philosopher’s authority (who he mainly cites in order to disagree). Later scholars have indeed noted the detailed observations that Frederick incorporates into his book. He observed the work of Saracen falconers and undertook experiments himself (for example testing the hatching of eggs by the heat of Apulia’s sun).

However it is his comments on the nature of the falconer that we begin to see something of his own experience of the art.

A bad temper is a grave failing. A falcon may frequently commit acts that provoke the anger of her keeper, and unless he has his anger under strict control, he may indulge in improper acts towards a sensitive bird so that she will very soon be ruined …

Falconers may be divided into several categories. The chief object of some is to use as food the … game which their falcons capture. … Others … think only of the enjoyment of securing a satisfactory flight for their birds. Others, again, boast and talk about the number of birds their falcons seize. Still others have no pleasure in such accomplishments and aspire only to have fine falcons, better trained than those of others …

The first name purpose of the falconer is objectionable because it leads to worry and exhaustion of his falcons … Nor is the second category more to be approved, since he who has always in mind to see his birds make brilliant flights is difficult to satisfy and is tempted to spur them on to intolerable exertions that are sure to weaken them … The third class must also be censured because they are likely to overstep the mark of good falconry and misuse their birds.

It is only the fourth group that is to be fully approved. A falconer in this class secures the best hunting birds available; he does not abuse them, but preserves them in good health and in proper training. He does not overwork his falcons …

One should always bear in mind that the very nature of wild birds of prey make them extremely diffident to man. …

Remember, also, how dependent the captive bird is upon her owner … [when] she is permitted for a time to freedom of action she must fly back to the falconer or wait quietly while he approaches to pick her up, again to be returned to the prison house — all of which is contrary to her every natural impulse. And there remains only the sense of taste through which bird and man meet on anything like even terms and common ground.

Wood and Fyfe translation, the Art of Falconry …, pp 151-152

These are just some of the observations Frederick makes on the art of being a falconer. He observes that man and bird live in entirely alien worlds as far as sight, touch and sound is concerned. It is only through the shared sense of taste that communication is primarily possible. It is obvious that he approaches the art by placing the bird at the centre and as a discipline which requires the human being to rise above human failings (such as anger).

Frederick’s last above quoted comment of equality and shared world between man and bird perhaps speaks to his experience as a lonely monarch for whom virtually all human company was conditioned by his political role. There was no possibility of equality with those in his court, nor of anything approaching friendship with other monarchs in the hyper-violent world in which he lived. He does not appear to see himself as “superior” to his birds, it is a relationship which must be cooperative if it is to work.

Frederick’s Patrimony – Empires and Books

Frederick’s sons certainly strived to maintain his imperial patrimony attempting to fight off armies which descended on them at the behest of the Pope. In this they failed. Manfred, Frederick’s natural son, ruled for a time as King of Sicily, but his life ended at the Battle of Benevento in 1266, defeated by Charles d’Anjou. Dante places him in Purgatory where he recounts his fate to Dante and asks him to tell his daughter he needs her prayers to attain heaven.

Then said he with a smile: “I am Manfred,

The grandson of the Empress Costanza,

Therefore, when you return, I beseech you

To my beautiful daughter go, mother

Of Sicily’s honour and Aragon’s,

And truth speak to her, if aught else be told."

(modified Longfellow translation, Dante, Purgatory 112-117)

This same Manfred also sought to preserve his father’s literary patrimony. He edited and extended his father’s book, as is evident from a version with his own marginal notes and additions and dedications to his father.

In Dante’s verses we also see, that although the glory of the Norman court was no more, a grand daughter of Frederick II, and a great great grand-daughter of Roger II, still sat on the throne of Sicily. Centuries later their descendants still ruled in the Kingdom of Naples.

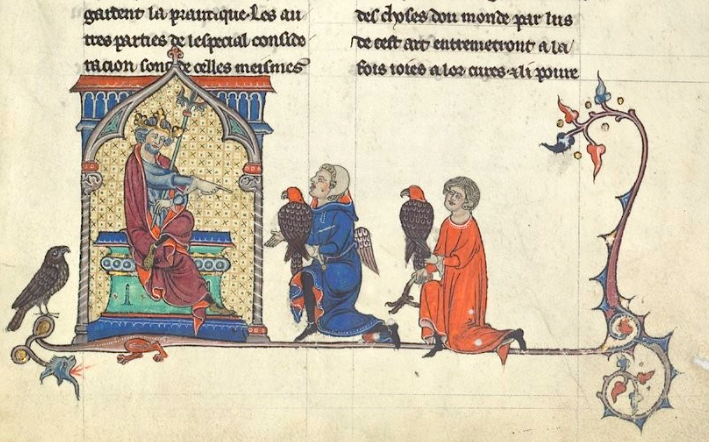

Opening Image

- Image of Frederick with falconers from a 14th century French edition of de Arte Venandi …

Sources

- Charles H. Haskins, The ‘De Arte Venandi cum Avibus’ of the Emperor Frederick II, The English Historical Review, Vol. 36, No. 143 (Jul., 1921), Oxford University Press, pp. 334-355

- Dorotea Weltecke, Emperor Frederick II “Sultan of Lucera” “Friend of Muslims”, Promoter of Cultural Transfer: Controversies and Suggestions, in Jörg Feuchter, Cultural Transfers in Dispute: representations in Asia, Europe and the Arab World since the Middle Ages

- Mattias Schramm, Frederick II of Hohenstaufen and Arabic Science, Science in Context 14(1/2), 289–312 (2001). Cambridge University Press

- Casey A. Wood and F. Marjorie Fyfe, The Art of Falconry being de Arte Venandi cum Avibus of Frederick II of Hohenstaufen, Charles T. Branford Company,

- The Mongol Empire a Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1, p 17

One Comment

Pingback: