Doctor Who? Trotula of Salerno

She was a doctor and a master of the art of healing who taught others. She is usually called Trotula, although her true name was Trota or Trocta. For three centuries medical works on the health and treatment of women circulated under her name: “The Trotula”. She has been lauded as among the finest doctors of the European Middle Ages or she has been so forgotten that it has been said that she did not even exist. It was only at the end of the 20th century that her true practice of medicine was recovered.

Salerno

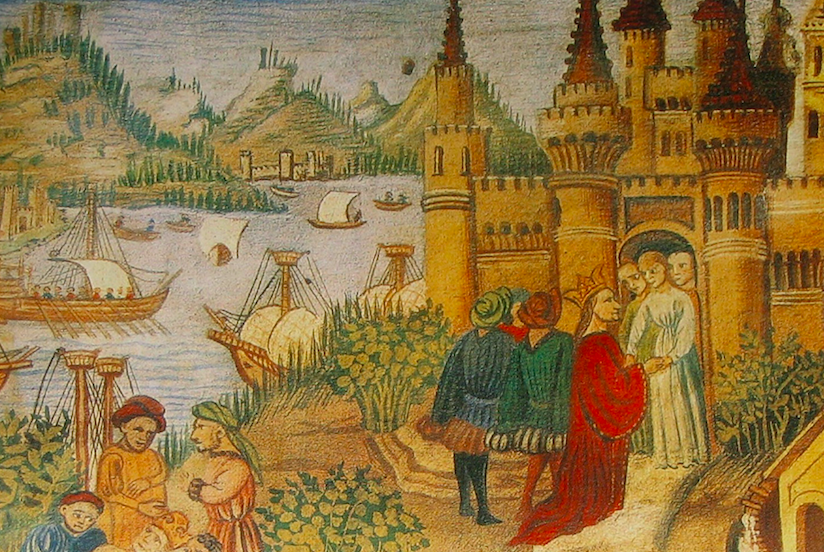

Trotula lived in Salerno: but the Salerno of Trotula’s time is almost as little known as she is herself. In her day it was a great city. Even before the Norman adventurer Robert Guiscard had conquered Salerno, it had been capital of a Lombard principality. Afterwards, it became the mainland capital of his growing Norman territory. Salerno was so impressive that William of Apulia, the chronicler of Robert’s deeds, was to effuse:

Rome itself is not more luxurious than this city;

William of Apulia, cited in The Trotula, p4.

It abounds in ships, trees, wine and sea;

There is no lack here of fruits, nuts, or beautiful palaces,

Nor of feminine beauty nore the probity of men.

One part spreads out over the plain, the other the hill,

And whatsoever you desire is provided by either the land or the sea.

The people of Salerno were diverse, boasting citizens of Lombard, Norman, Greek and Jewish heritage (its Jewish population of 600 was more than any other centre in southern Italy). It was one of the major nodes of a maritime commerce at a central crossroads of the Mediterranean. In Trotula’s time, Salerno was one of the primary cities of a united southern Italy and Sicily: a situation that had not existed for half a millennium.

of pulpits within the Salerno Cathedral

Such was the fame of Salerno in this era that it drew scholars from across Europe, such as the English monk named Adelard of Bath travelled to Salerno to study the “learning of the Arabs”. Not far away, at the monastery of Monte Cassino a translation centre was established to translate Arabic works of interest to a Europe which awaking to the scientific advances occurring in the Islamic world to their south and east. As we shall see below “the” Trotula (a book rather than a woman) is connected with Monte Cassino.

The Medical School of Salerno

Medicine was the field for which Salerno was most known in this time and the practice of medicine that grew up there was known as the Scuola Medica Salernitana. Benjamin of Tudela who visited Salerno in the 1160s referred to Salerno as “the principal medical university of Christendom“. Another scholar Ordericus Vitalis in the first half to the twelfth century identifies it as the “seat of the chief schools of European medicine from antiquity”.

A legend in relation to its creation was that it was the work of Rabinus Elinus, Adala and Magister Salernus; respectively a Jew, a Greek and a Latin. As with most legends there is a grain of truth; although later scholarship is unable to verify the legend. What has been demonstrated is that the monks of Monte Cassino and the medicine practised in Salerno were closely linked.

The thread that linked them (and the legends) together was Constantine the African. He is said to have been a native of “Carthage” – an impossibility – unless the term referred generally to the area of Tunisia (in which the long destroyed ancient Carthage is found). He appears to have travelled widely to such places as Egypt, Baghdad, Babylon (also long destroyed at the time) and India. His medical knowledge caused him to be suspected of sorcery and he ultimately fled to Salerno, where on one account a visiting prince from the east noticed him and pointed him out to Robert Guiscard. As a result he served for a time as private secretary to the Norman duke. Soon enough however he withdrew to a monastic life in Monte Cassino where he translated at least 20 major treatises on medicine from Arabic into Latin. (Notably his translations typically did not credit the Arabic originals.) Some of his works were to be connected with Trotula’s name as we shall see below.

Trotula – The Life of a Woman Physician

So far we have learnt virtually nothing about our Trotula and indeed she appears in frustratingly few references although so widely known as to be commonly called “Mother Trot”. Her name appears as one of the more prominent authorities in the earliest compendium of the medicine of Salerno (the Compendium Salernitanum). In the 1050s a learned monk visiting Salerno skilled in medicine among the practitioners of Salerno found that only one: a “learned woman” who excelled him in skill. Although this might have been Trotula; it is just as likely to have been one of a circle of skilled women who practised medicine in Salerno at this time.

One legend says that Trotula was married to John Platearius, himself a physician, and that she came of the “distinguished and noble” Ruggiero family. But in truth little is known and such legends are of more recent confection. Trota was a common name in southern Italy in the twelfth century, and the name appears seventy times in Salerno records of the time: but which one is our Trota?

The earliest reference to her occurs in a medical treatise where she is able to heal a woman’s gynecological condition that other doctors had been unable to treat. She is, in the same work, referred to as “acting” as a professor or teacher. It is sad so little is known of a woman whose named was so renowned.

Some (male) scholars indeed claimed that there was no woman and in fact that Trota was “Trotus”, a male. Another male scholar claimed that “Trot” was a reference to “running about”. Another asserted that “Trotula” was a transcription error for an ancient “Eros Julia”. Suffice to say that modern scholarship has debunked such theories, although it is unable to tell much of her actual life.

Glimmerings of her life are fictionalized in works such as the Mistress of Death by Ariana Franklin and (in Italian) Trotula by Paola Presciuttini (who takes the legends as the core of her story).

What can be said with some certainty is that Trotula was not the only woman who practised the healing arts in Salerno. She was likely one of many women healers who practised medicine in the city. What makes her particularly famous and unique, beyond her exceptional skills, is that her writings have come down to us in the modern day. But she was the exception rather than the rule.

As Benton observes:

The professionalization of medicine in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries led to an exclusion of women practitioners from the best paid and most respected medical positions. Male doctors controlled the teaching and theory of women’s medicine, and their gynecological literature incorporated male experience, understanding and learning. … the practice of medicine in the Christian West moved from a skill to a profession ~ with academic training based on authoritative learned literature ~ with degrees and licenses~ and with sanctions against those who practiced medicine without a license.

John F. Benton, 1983, 84

Monica Green, one of the most prolific scholars of Trotula tells us the fate of Perretta Petona, a woman who practised surgery in the fifteenth century in Paris. She was charged with the unlicensed practice of surgery. Rather than denying she practised medicine, Perretta referred to the traditional learning handed down to her by her relatives and other practitioners, explaining her considerable success in the profession. It did her no good. For she was illiterate and interrogated by the university trained men. She was mocked, humiliated and driven from practice. It might be added that the theories which dominated the book learning, in which the male scholars so prided themselves, were shown in the course of time to be almost entirely nonsense.

Trotula’s Book: Practica Secundum Trotam

It was not until 1985 that a work definitively attributable to Trotula was discovered by John F. Benton in a library in Madrid. This work, as suggested by its title, is the practice of medicine according to Trota. Another better known work “the treatment of illnesses” written about 1160 was shown by Benton to contain many unattributed extracts from the Practica. Here at last was the smoking gun for the existence of Trotula.

What about the book the Trotula? For centuries it had been attributed to Trota but the story is much more complicated. Over the centuries it in fact evolved into a compilation of three works, each with its own unique story. The Book on the Conditions of Women, On Treatments for Women and On Women’s Cosmetics were those three works.

Constantine the African, it turns out, has a role to play in the creation of the Conditions of Women, for this work draws heavily from his Viaticum, itself a copy of a medical work by the Arabic writer Ibn Al Jazzar. His work was in turn grounded in the theories of the ancient Greek Galen who believed in the “four humours”. In short however the Conditions of Women turns out largely to be the work of men. It could not have been written by Trotula.

On Women’s Cosmetics, as Green demonstrates was also written by a man for other men who might be able to trade on this knowledge. However the work draws on observation of the practice of cosmetics by women in the author’s time and place. In Salerno, cosmetics from the Arabic speaking world as much as from Europe were fashionable.

The most interesting of the three works for the life of Trotula is On the Conditions of Women. In 2008, Green established through a careful analysis of the text that it must have been written by a woman: perhaps she was our Trotula (the most natural assumption given that the work is attributed to her). It is clear that this woman is a skilled physician, someone who treats disease. Moreover the work is written for other women. It thus points to community of women who were not only practising medicine but were literate; and who were taught by a female master of their art.

Legends of Salerno Come Back to Life

Daremberg, a medical historian visited Salerno in 1849, searching for the heroes of the history which was his life. His search was fruitless.

… I wandered sadly through the streets; I sought in vain for some trace or reminder of the illustrious masters whose voice had resounded in the midst of the most troubled ages. … Who remembered the beautiful Trotula or the artful Constantine? In default of a great medical school what monument, piously consecrated to all the glories of the school, could recall to me some features of its early history? No echo of tradition, not one stone of the ancient edifice; not one manuscript in a single library …

The School of Salernum: An Historical Sketch, pp 54-55

If Daremberg could return and travel to Salerno today he would not find things so bleak for lovers of medical history. Indeed the memory of the School of Salerno is now treasured in a Virtual Medical School of Salerno found in the old city. Here a virtual journey can be taken into the medicine of the medieval ages. Salerno however has many treasures; a museum full of ancient artefacts, an outstanding collection of medieval carved ivory, a small but wonderful gallery and a Norman era cathedral from the days of Robert Guiscard.

Images

First image: A female healer of the Middle Ages in a fourteenth century manuscript: perhaps Trotula.

Other images are own work.

Sources

Monica H. Green (ed), The Trotula A Medical Compendium of Women’s Medicine Edited and Translated by Monica H. Green, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001

Monica H. Green, Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology. Oxford University Press, 2008.

Henry Ebenezer Handerson, The School of Salernum: An Historical Sketch of Mediaeval Medicine, New York, 1883

John F. Benton, Trotula, Women’s Problems, and the Professionalisation of Medicine in the Middle Ages, Humanities Working Paper 98, Dec 1983, 84.