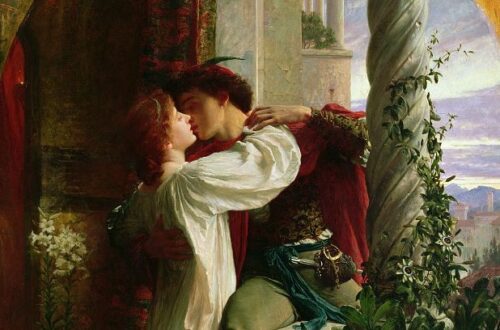

Sicily’s Medieval Map of the World

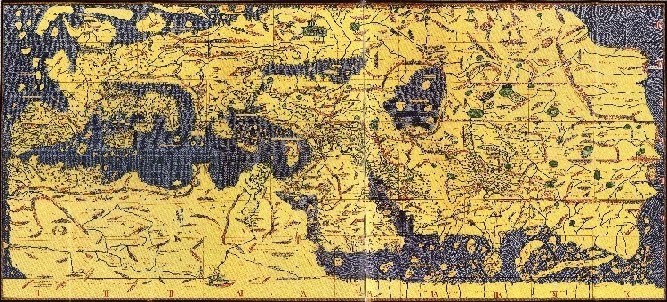

It must have been magnificent to see: a vast world map made of pure silver. For three centuries no better map was made. The glittering silver original graced the Palermo court of Roger II, the Italo-Norman King of Sicily and Southern Italy. It was made for him by his scholar geographer friend Muhammad Al Idrisi.

The map represented one of the most ambitious scientific undertakings of its day taking more than 15 years to complete. It was imagined by a king famed for his learning at the height of his kingdom’s powers. It took almost 150 kilograms of silver to make and showed the world in 7 climates. To make the map, knowledge was collected from near and far. In preparing it, Al Idrisi scoured the then existing geographical works available in Arabic. For years visitors arriving in Palermo would be questioned about their knowledge of distant places and the results incorporated into the ever more complete map. This was not a work of myth and legend. It was a comprehensive collection of reliable knowledge about places east and west.

As well as the map, the project included a detailed book documenting the known countries and cities of the world. Although the silver original survived only a short time, Al Idrisi’s book, known as the Book of Roger, has survived to the modern day: containing both sectional maps and a narrative description of the world.

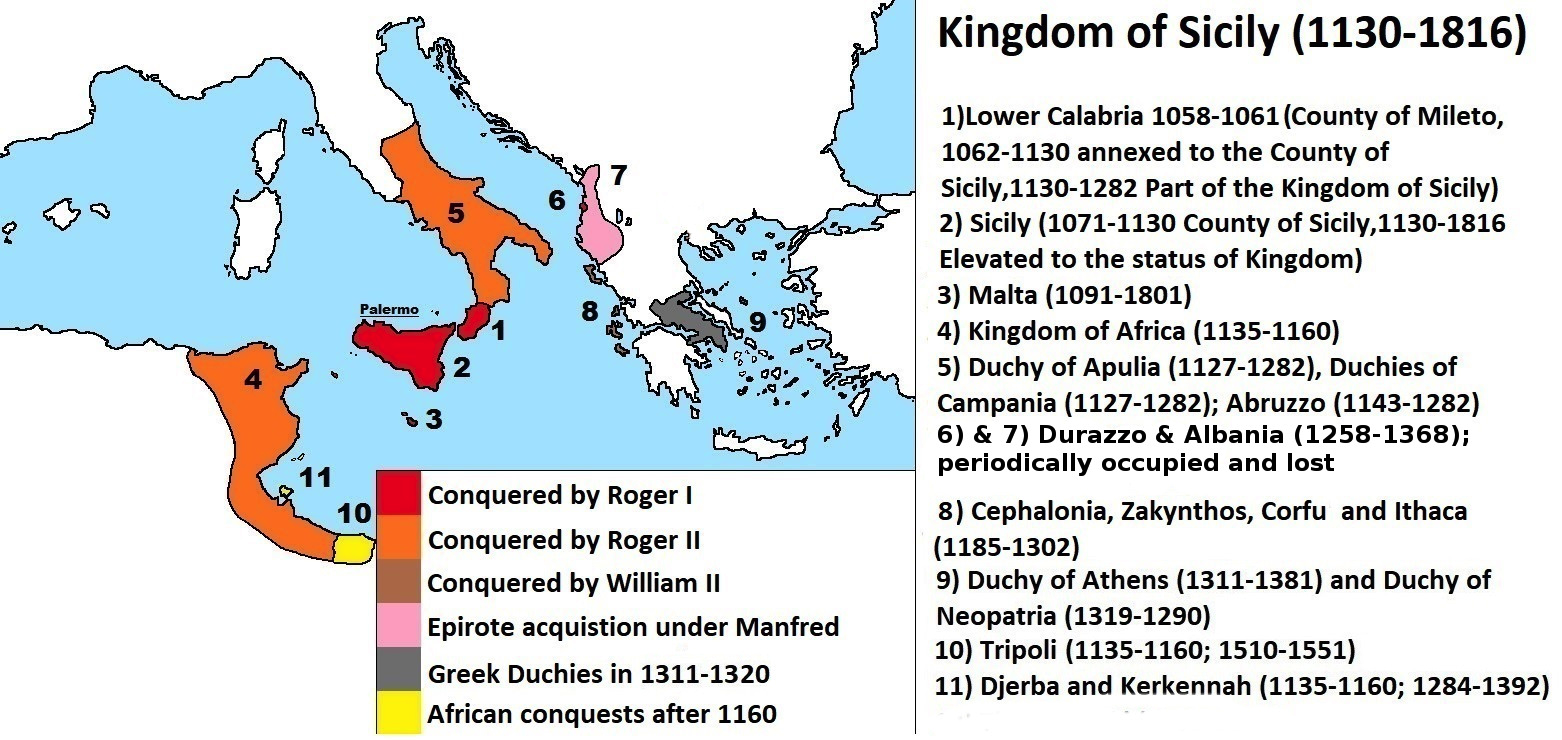

The Norman Kingdom of Sicily

The kingdom that Roger II ruled is not always familiar and so requires introduction. Norman adventurers had began to arrive in southern Italy in the 900s attracted initially as swords for hire in the warfare that raged there. German-Lombard kingdoms, the Roman-Byzantine Empire, maritime city-states such as Amalfi and Naples, and Muslim adventurers were all part of this world. For two hundred years Sicily itself had been the Muslim Emirate of Sicily. Suffice to say that the Normans became part of this world establishing domains that expanded over time. By Roger II’s day, their original paymasters and the old local rivals had been destroyed, driven out or forced into submission. The Norman northern boundary now ended where the lands of the Pope began, and their southern boundary extended to the southern side of the Mediterranean and beyond the boundaries of modern Tunisia.

Although the Norman kingdom was not to endure, and it always battled enemies within and without, the political geography of southern Italy that the Normans created was to remain largely in place until the 1860s. Their role in Italian history is thus more than of passing interest. The Norman kingdom is widely famed for the brilliance of its fusion of diverse cultural elements – Byzantine Greek, Latin Catholic and Arabic Muslim.

For a time, it became a centre of learning and culture attracting scholars of world renown to its court. Something of its character is demonstrated by the names of its officers, as Norwich recounts. The highest officer of the land under the king himself was the Emir of Emirs. This office was held by George of Antioch an Arabic speaker from the Levant, Sicily’s greatest admiral. The civil service combined models from the diverse cultural heritage of the kingdom. Part of the land was held on the Fatimid model and divided and administered as divans. Other lands were administered by Greeks on old Roman models. Models were also drawn from the Anglo-Norman exchequer. In the palace emirs, seneschals, archons, logothetes, protonotarii, protonobilissimi served side by side. Moreover, we see something of Roger’s character from the following:

By the 1140s [Roger] had given a permanent home in Palermo to many of the foremost scholars and scientists, doctors and philosophers, geographers and mathematicians of Europe and the Arab world; and as the years went by he would spend more and more of his time in their company. … whenever any scholar entered the royal presence, Roger would rise from his chair … take him by the and and sit down at his side. During the learned discussions that followed whether in French, Latin, Greek or Arabic, he seems to have been well able to hold is own.

Norwich, the Kingdom in the Sun, pp 100-101 (see more generally for discussion above).

The buildings the kingdom left behind, and which beautifully illustrate this fusion can still be visited, particularly in Palermo. For example, Monreale (standing on a high ridge behind Palermo) hosts a Cathedral from this era. In it, Christ enthroned in Byzantine mosaic dominates the Cathedral, while geometric patterns in the Muslim fashion and Latin Medieval sculpture adorn parts of the building. It is only one of the architectural marvels that survive from this period and make Palermo a well-worth part of a visit to Italy.

Muhammad Al Idrisi

Muhammad Al Idrisi could trace his ancestry back to the prophet Muhammad and was a member of the Hamdudid clan, whose Caliphs of Cordoba had ruled there for a time. His own ancestors had been nobles of Malaga in Spain who had moved to Ceuta when political conditions had changed in their homeland. Al Idrisi was born in 1099 in Ceuta, Morocco, dying there in 1166. He was however to live a life of adventure. Al Idrisi was educated in Cordoba, then a leading centre of learning. This scholarly foundation was expanded by wide travel, including to Asia Minor, southern France, England, Spain and Morocco.

When he was nearing 40, Roger II invited Al Idrisi to come to his court where he became a firm friend of the monarch. Roger’s commission to him to produce an account of the countries of the world and the silver world map left Al Idrisi fabulously wealthy. He was only to leave Palermo when his patron and friend Roger II passed away. With the death of the great king, the kingdom fell into revolution and within 20 years Al Idrisi’s great map was to be destroyed in a riot. It was stripped of its silver when looters sacked the palace in the reign of William the Bad.

The Book of Roger

Al Idrisi’s book however survived and is widely known as the “Book of Roger”, after the name of its patron. In correct Muslim usage Al Idrisi begins his preface with an extended praise of a merciful and beneficent God. This is followed by an equally lengthy tribute to Roger: the illustrious Roger, King of Sicily, Italy, Lombardy, Calabria and Roman Prince. As he introduces his work, although he has drawn on the works of numerous Muslim geographers who preceded him, he first mentions Ptolemy, a reflection of the ancient heritage on which his knowledge is built. As would be expected of a learned figure of science even in the Middle Ages, he is well aware that the Earth is a globe.

That which results from the opinions of the philosophers, illustrious scientists and observers skilled in the knowledge of celestial bodies, is that the Earth is round like a sphere, and the waters adhere to it in a natural equilibrium in which no variation is found.

Géographie D’Édrisi, p 2, own translation from French

The world is organised in seven climates from west to east. Drawing on the learning of India and Ancient Greece, Al Idrisi estimates the circumference of the Earth at 33,000 or 36,000 miles.

Al Idrisi describes cities, lands and seas from China to the edge of the known west. The description of course includes Roger’s own kingdom. Here we only very briefly sample some of this description; which we might expect to be least likely to be inaccurate. Often cities are just named, but Al Idrisi also provides distances as travellers itineraries, and in some cases brief descriptions.

The present section contains a part of Calabria, the country of the Lombards, the majority of the Venetian Gulf and the principal cities which are situated on its shores. Among these cities, on the eastern side we find: Rovigno, Pola, Brana, Moschenizza, Santo Baoulos, Zara, Ragusa, Spalatro, Gorizza, Cattaro, Antivari, Dulcigno, Durazzo, Butrinto, Canina, Camanova and Kira.

And on the eastern shore we find: Brindisi, Simona, Monopoli, Canborsano, Molfetta, Bisceglia, Trani, Barletta, Fani, Sebnita, Rodi, Lesina, Campo Marino. All these places belong to the country of the Lombards, on the eastern shore.

Géographie D’Édrisi, Volume 2, p 261, own translation from French

Some of these cities are familiar from their survival into the modern day. Others have disappeared. Venice’s maritime dominance of the Adriatic is already evident. The reference to “Lombard” lands is curious, but is recorded as the perception of the time by Al Idrisi. Bari is described further on as “one of the principal cities of the Lombards, a place where ships are built, much renowned among the Christians.” The Lombard character of this part of Italy has largely been forgotten, although Lombard buildings can still be found at the sacred site on Monte Sant’Angelo of the Gargano.

Naples on the opposite side of Italy appears as a centre of commerce and trade and Amalfi appears in its maritime guise.

Naples is a beautiful city, ancient, flourishing, populated, provided with bazars where one is able to undertake profitable commerce in merchandise and items of every kind. …

Amalfi is a flourishing city with a strongly fortified port on the land side. If one wishes to embark to sea it is easy to do so. The city is ancient, surrounded by walls and with a large population.

Géographie D’Édrisi, Volume 2, p 257-258, own translation from French

Images

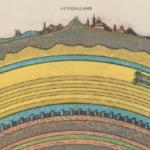

The image at the beginning of this article is a reconstruction of Al Idrisi’s geography made by joining together sectional maps found in the Book of Roger. The maps are held in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. In the original south is at the top.

Kingdom of Sicily By Trey Kincaid and Sarracinu97 [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

A segment from Al Idrisi’s maps showing southern Italy and the south western Balkans.

Sources

Norman Julius Norwich, The Kingdom in the Sun 1130-1194, The Normans in Sicily Volume II, Faber & Faber, 1970, 2018, particularly pp 101 and following

La Géographie D’Édrisi Traduite et Annotée par P.A. Jaubert, Philo Press Amsterdam

History of the Moorish Empire in Europe, pp 460-462

The Encyclopedia of the History, Technology and Medicine in the Non-Western World, p 128