Lingering in Limbo: Dante’s Inferno

Limbo, it turns out, isn’t so bad, even if is found in the first level of Dante Alighieri’s hell. As Dante’s allegory of the journey of the soul continues, it will take him to a beautiful castle inhabited by the good and the great. Far from suffering the tortures of hell, although they can never leave, they are surrounded by meadows and hang out in erudite splendour. But before Dante gets there he has more adventures.

Beatrice sends Virgil to the Rescue

The ghost of Virgil, a long dead Roman poet, has shown up just in time to take on the job as Dante’s guide. But what’s in it for Virgil?

In accordance with the orthodoxy of Dante’s time and place, Virgil was forever consigned to hell. This was because, Virgil, having died before Christ was born, was a pagan and thus never baptised.

Beatrice, Dante’s beloved, who is in heaven, comes to know Dante is in need of help. Saint Lucia (a symbol of light) brings the news after the Virgin Mary herself makes the danger known to Lucia. Beatrice descends into hell to commission Virgil to rescue Dante. Beatrice promises to put in a good word for Virgil whenever she is before the throne of heaven and Virgil takes up his task.

As Dante’s courage fails, Virgil lifts Dante’s spirits by sharing the words Virgil has himself heard from Beatrice:

I’ son Beatrice che ti faccio andare;

vegno del loco ove tornar disio;

amor mi mosse, che mi fa parlare.

Quando sarò dinanzi al segnor mio,

di te mi loderò sovente a lui”. ...

E venni a te così com’ ella volse;

d’inanzi a quella fiera ti levai

che del bel monte il corto andar ti tolse.

For I am Beatrice who send you on;

I come from where I most long to return;

Love prompted me, that Love which makes me speak.

When once again I stand before my Lord,

then I shall often let Him hear your praises.’ ...

And, just as she had wished, I came to you:

I snatched you from the path of the fierce beast

that barred the shortest way up the fair mountain.

Inferno Canto II, Verses 71-74, 118-120 with Mandelbaum translation

Like the three beasts who barred Dante’s way, and which can be thought of as representing three vices, the three maidens of heaven are said to represent heavenly virtues which aid Dante’s path.

The Gates of Hell

In Canto III, Dante and Virgil approach the gates of hell and dark words engraved in the gateway tell them of what is ahead.

‘Per me si va ne la città dolente,

per me si va ne l’etterno dolore,

per me si va tra la perduta gente.

Giustizia mosse il mio alto fattore;

fecemi la divina podestate,

la somma sapïenza e ’l primo amore.

Dinanzi a me non fuor cose create

se non etterne, e io etterno duro.

Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch’intrate’.

THROUGH ME THE WAY INTO THE SUFFERING CITY,

THROUGH ME THE WAY TO THE ETERNAL PAIN,

THROUGH ME THE WAY THAT RUNS AMONG THE LOST.

JUSTICE URGED ON MY HIGH ARTIFICER;

MY MAKER WAS DIVINE AUTHORITY,

THE HIGHEST WISDOM, AND THE PRIMAL LOVE.

BEFORE ME NOTHING BUT ETERNAL THINGS

WERE MADE, AND I ENDURE ETERNALLY.

ABANDON EVERY HOPE, WHO ENTER HERE.

Inferno Canto III Verses 1-9, with Mandelbaum translation

Hopelessness is the condition of souls which are within. In graphic scenes in the lower levels of hell, the travellers will discover that the “punishments” of hell are literally the misdeeds of life.

However on this level we learn of two kinds of hopelessness. The hopelessness of those who will never come to heaven (a fate announced to the approaching dead by the ferryman Charon); and an even worse hopelessness of those who will not even be allowed to cross the river and are rejected by both heaven and hell. These are those who lifeless in life, taking part neither for good nor ill, will be deathless in death. Such are the thoughts that Dante presents to us.

Did Virgil Inspire Dante’s style as he claims?

Although Dante claims in this Canto of the Comedy to have taken his style from Virgil, there is little in Dante’s poetry (before he writes the Comedy itself) to back up the claim. Dante’s love poetry has little to do with Virgil. Nor is Dante’s famous “terza rima” (three line rhyme) inspired by Virgil, for rhythm not rhyme was the defining characteristic of Roman poetry.

The story of the Comedy however is in part based on Book VI of Virgil’s own Aeneid, which tells the story of Aeneas’ descent into a pagan underworld. At least Dante wants us to believe that Virgil is his primary precedent.

Indeed we can see some familiar images from the Aeneid in Dante’s account. Like Dante’s Charon, the eyes of Virgil’s Charon also glow like burning coals. In both accounts Charon challenges the right of the living travellers to proceed. In both versions the punishment is made to match the crime. Minos is the judge of the dead both for Virgil and Dante. Even the exclusion of pagans from heaven for the absence of the ritual of baptism in Dante’s world, has its parallel in the exclusion of the dead who have not received pagan burial rites in Virgil’s underworld. They are condemned to remain on the shore of the underworld for 100 years.

With Virgil’s help, who convinces Charon to let the living Dante pass, Dante crosses the river Acheron and arrives in the first level of hell proper. This is Limbo. Here Dante describes the souls of the unbaptised (primarily children) who form a great static wood and we will soon come to the castle.

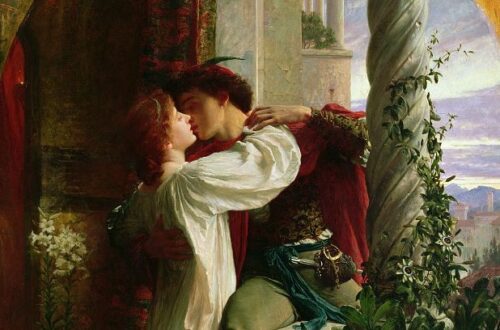

In the Company of Poets

As they proceed they see figures who hail Virgil from the distance. They are the great poets of history who welcome Virgil back like a conquering hero.

79 Intanto voce fu per me udita:

80 «Onorate l’altissimo poeta;

81 l’ombra sua torna, ch’era dipartita».

82 Poi che la voce fu restata e queta,

83 vidi quattro grand’ ombre a noi venire:

84 sembianz’ avevan né trista né lieta.

85 Lo buon maestro cominciò a dire:

86 «Mira colui con quella spada in mano,

87 che vien dinanzi ai tre sì come sire:

88 quelli è Omero poeta sovrano;

89 l’altro è Orazio satiro che vene;

90 Ovidio è ’l terzo, e l’ultimo Lucano.

Meanwhile there was a voice that I could hear:

“Pay honor to the estimable poet;

his shadow, which had left us, now returns.”

After that voice was done, when there was silence,

I saw four giant shades approaching us;

in aspect, they were neither sad nor joyous.

My kindly master then began by saying:

“Look well at him who holds that sword in hand

who moves before the other three as lord.

That shade is Homer, the consummate poet;

the other one is Horace, satirist;

the third is Ovid, and the last is Lucan.

Inferno Canto IV, Verses 79-90, Mandelbaum Translation

In an act of poetic chutzpah, Dante has these great poets enrol him as the sixth of their great company. Like his claim to have followed in Virgil’s steps, this is a promise on which Dante now has to deliver in the rest of the Comedy.

The Castle

They continue on together and come to the Castle and within is a who’s who of history’s non-Christians. The castle is surrounded by seven walls around which flows a fair stream. He and Virgil cross over the stream as if walking on land. They find within a place filled with light. Dante then begins to enumerate figure after figure. Figures from ancient Trojan mythology like Electra and Hector; from Roman history like Brutus and Caesar. Saladin is there, set apart from others. Then the great philosophers Aristotle and Plato and the great scientists and doctors of ancient Greece and Rome. Among them the Muslim philosophers Avicenna and Averroes. The faces of this company are marked with authority. They speak rarely and their voices are gentle.

All this is hardly “hellish”, and reads like the kind of place that Dante himself might not have minded spending eternity. In part it adapts Virgil’s description of the pagan Elysian Fields in the Aeneid. Dante’s castle symbolises some of the highest achievements of civilisation in the sciences and the arts. Even a figure like Caesar is in Dante’s world view symbolic of good government (as he believed a strong “Roman” Emperor was the solution to the political problems and conflict of his time). Like the places of retreat in the physical world in which Dante lives, it posits an exalted existence in an “ivory tower” separated from the ghastly fate which is the common lot of a larger mass of humanity submerged in vices of lack of self-control, violence and malice. The castle, is in some senses, a beautiful illusion, as Dante has discovered in the trajectory of his own life.

The vision is one that at least some of Dante’s contemporaries saw as heretical for its essentially pagan inspiration and was a source of embarrassment to his defenders.

For Dante the traveller, this place full of light is not the end of the journey. To reach his true goal he must first travel on through the dark places of human existence: “where nothing shines”. If we are to follow the journey such places must be traversed, but what Dante wishes to tell us of, is the “good he found within” (Inferno Canto I, Verse 8).

La sesta compagnia in due si scema:

per altra via mi mena il savio duca,

fuor de la queta, ne l’ aura che trema.

E vegno in parte ove non è che luca.

The company of six divides in two;

my knowing guide leads me another way,

beyond the quiet, into trembling air.

And I have reached a part where no thing gleams.

Inferno Canto IV Verses 148-151, with Mandelbaum translation

Image

Spiriti magni, Priamo della Quercia (c.1403–1483)

Sources

Barbara Reynolds, Dante The Poet, the Political Thinker, the and the Man, I.B. Taurus London, 2006, pp 127-130

John A Scott, Understanding Dante, University of Notre Dame Press, 2005, p 209-210

Amilcare A Iannucci, Dante’s Limbo at the Margins of Orthodoxy, in James Miller (ed), Dante & the Unorthodox The Aesthetics of Transgression, Wilfrid Laurier University Press 2005, p 63-82

Dante Princeton Project, Inferno Canto IV