Muslim Lucera and the Holy Roman Emperor

Truth is stranger than fiction, it is said and so it is for the story of Muslim Lucera. It is a story entwined with the life and times of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. We cannot call Muslim Lucera the Muslim “capital” of the Holy Roman Empire, but for a time, it very nearly was. Lucera hosted one of Frederick’s many palaces and castles. One of his primary palaces was only 30 kilometres distant, in the city of Foggia, and Frederick himself has been called the “Sultan of Lucera” (although the label is a wild exaggeration). So let us explore the story.

The city of Lucera still stands on a strategic hill which rises in the heart of the Tavoliere plain, in south-east Italy. Founded before the Romans, the city suffered periodic destruction in the fortunes of war. In this respect, she shared the fate of the cities of the region, who were frequently the target of such destruction, though often they would spring to life again. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the hill of Lucera either hosted an existing community or it was nothing but haunted ruins (depending on the source you follow). Just the same, for the Emperor Frederick, Lucera was a solution to a considerable problem.

Frederick himself is a curious figure. He was the son of the German Holy Roman Emperors on his father’s side and on his mother’s side (in spirit and flesh) the grandson of the Roger II, the greatest king of the Norman kingdom of southern Italy. Frederick has a reputation for brutality but also a love of scholarship. He became a ward of the Pope in his infancy, as his mother died when he was only three. But as he grew to adulthood his relationship with the Pope became strained and ultimately they became enemies.

The trouble between Emperor and Pope was older than Frederick’s own time, for we are in the time when the western Christian world was in turmoil and violence over whether Pope or Emperor was to be supreme authority. It is a world whose echoes we can still hear in Umberto Eco’s book The Name of the Rose. In this world the partisans of Pope (the Guelphs) and partisans of the Emperor (the Ghibellines) confronted each other again and again both on and off the battlefield.

The world of his time was also divided between the Christian north and west and the Muslim south and east. Despite these sometimes violent fractures, the divides were never sharp in a world of shifting alliances in which Christians and Muslims often found themselves on the same side. It was moreover a world of trade and cultural exchange. The scientific and cultural achievements of the Arabic speaking world were a thing to be emulated and admired. Frederick, like his Norman forebears spoke not only languages such as Pugliese, Latin and Greek, but also Arabic. In Frederick’s day it was a language of science and poetry of Europe; as much as Africa and Asia. Among Frederick’s works was a book on the art of falconry, which reflected not only European learning, but also Arabic sources on which Frederick drew. Although his many detractors threw many accusations at him, even his enemies admitted the greatness of his achievements.

Frederick had promised the Pope that he would undertake a crusade to re-capture Jerusalem from the Muslims. Yet it was a promise he seemed loathe to keep, even (according to Papal partisans) feigning illness to avoid the fulfilment of his pledge. Frederick II likely knew his business. His most dangerous enemies were not to the south, but rather his fellow Christians, whose rebelliousness and dynastic squabbles were endless and who were much closer at hand. In frustration, the Pope excommunicated the Emperor: declaring attacks on him lawful.

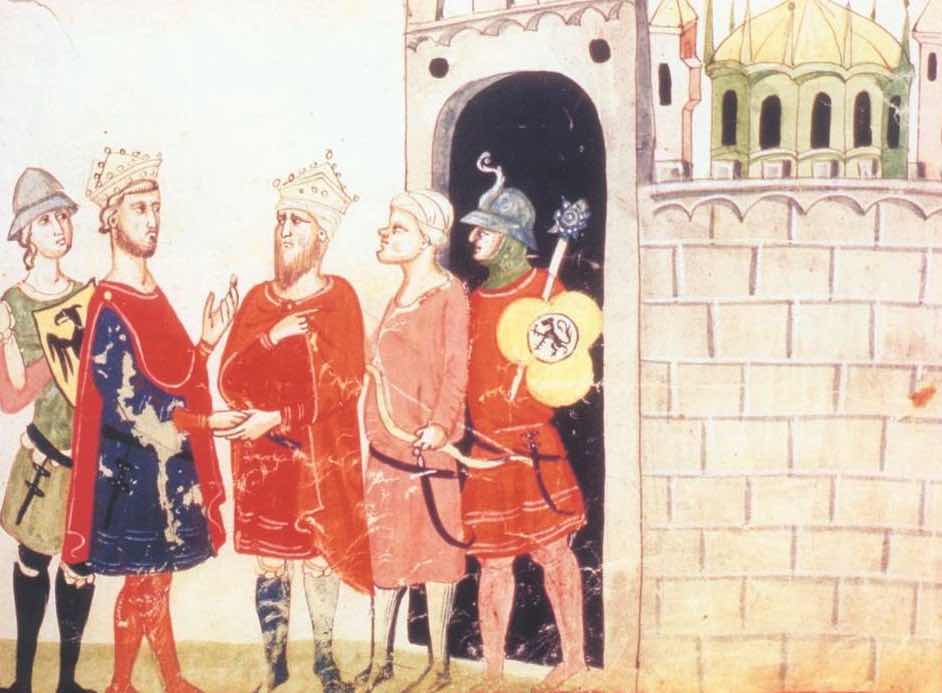

Frederick II responded, with some irony, by fulfilling the promise, but on his own terms, and not as agent of the Pope. He negotiated a peaceful handover of Jerusalem from its Muslim rulers (apart from the Al Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock). For their own reasons, the Muslims also wished to avoid a war with the western Christian Emperor.

Frederick II then crowned himself King of Jerusalem. His less than subtle demonstration of divine favour was no doubt a cause of some irritation and perhaps embarrassment to his enemies, given the excommunication under which he had been placed. Like most medieval monarchs, Frederick’s life is a catalogue of battles, rebellions, diplomacy and political intrigue. Ruling a realm that stretched from Denmark to Jerusalem, he had more problems than most.

In such a context, the problem that brought about the creation of a Muslim Lucera was not the greatest Frederick faced, but it was not insignificant either. It was perhaps more important to Frederick, for he loved his southern Italian domains, spending most of his reign there.

For two centuries Sicily had been a Muslim kingdom. Afterwards, for a time the Siculo-Norman kingdom had fused together its Greek, Latin and Muslim heritage. Its most able Norman rulers were able to maintain harmony between the diverse communities of their kingdom through a careful balancing of communal interests. Yet times were changing. Latin influence was growing and the Greek and Muslim populations was fading into subordination as Latin power grew. The king William II placed most of the Muslim population under control of the church hierarchy. It was a formula for conflict and led to a rebellion of much of the Muslim population of Sicily from the 1180s. A generation later they were still fighting for their liberty. In the end their struggle was doomed. Frederick led his forces against them and from the 1220s to the 1240s he deported their entire population from their beloved island, forbidding their return.

They were resettled at Lucera, depopulating the parts of Sicily from which they came. The aims were clear enough: move a rebellious population far from co-religionists in Africa, and put them in the middle of a plain without easy access to the sea. Estimates of how many were relocated vary, from 15,000 to 60000. Whatever the number, it was very large for the 13th century, rivalling or significantly exceeding the population of the city in the mid-nineteenth century. Undoubtedly the exodus was accompanied by much suffering, although the archeological evidence suggests it was well organised and orderly, for nothing was left behind.

For Frederick the venture had clear economic purposes as well. The Muslims of Lucera were to be “servants of the crown”. His idea of the wealth they could generate is clear from his “investment” in a gift to them of 6000 head of cattle (later to be subject of imperial taxation). They were not allowed to leave the city. They were skilled, practising a range of professions as reported by Metcalfe:

… rearers and keepers of pigs, goats, sheep, horses, donkeys and bees …, shepherds, butchers, tanners, saddlers, falconers and huntsmen, millers, bakers, potters, stonemasons, cotton growers, vintners and fruit growers, tailors, tentmakers, carpenters, soldiers, guards, castellans and stewards, in addition to a range of smiths and metal-workers, buglers, musicians, bath-house keepers, notaries, minor officials and qa’ids.

Alex Metcalfe, The Muslims of Medieval Italy, p288

Muslim Lucera became prosperous economically, providing an ongoing source of revenue for the Emperor. Some of the occupations above however had military connotations. In their new context, the Muslim population now far from its origins, and surrounded by hostile communities, became intensely loyal to the Emperor. They manufactured weapons for him and provided tens of thousands of warriors (particularly archers and cavalry). Here were subjects on whom he could now rely. Subjects who would stick with him, and who were immune to excommunication, his or theirs.

Frederick loved nothing more than passing his days in Puglia, including indulging in his love of hunting. He administered his empire from his mobile court in the many castles and residences he had there. But trouble was never far away, particularly his troubles with the Pope. In 1245 Frederick was again excommunicated. Among the grounds of excommunication was his alleged closeness to the “Saracens”. This of course was not at the heart of the trouble. It was the still unresolved question of Pope vs. Emperor. In these strange times, the new people of Lucera were hostages, and more trouble was in store for them (but that is a story for another time). It is perhaps right to give the last word to Ibn Hamdis, a Muslim poet of Sicily, who before the Muslims of Lucera, had ended in his life in exile:

I remember Sicily, and my grief

is awakened by remembering her

The abode of youthful pleasures stands empty

and its residents were a people of elegance

But if I have been driven out of paradise

then let me still recount its story

If weeping were not salt water,

I would think my tears were a river

At twenty, I laughed with youthful pleasures

at sixty, I cry for her burdens

Ibn Hamdis, in Karla Mallette, The Kingdom of Sicily, 1100-1250 : A Literary History, p 134

Sources

Julie Anne Taylor, Muslims in Medieval Italy: the Colony at Lucera, Lexington Press, 2003

David Abulafia, The Last Muslims in Italy, in Dante Studies, with the Annual Report of the Dante Society, No. 125, Dante and Islam (2007), pp. 271-287

Julie Nottingham, Lucera Sarracenorum: A Muslim Colony in Medieval Christian Europe, in Medieval Studies, 1999, 43

Alex Metcalfe, The Muslims of Medieval Italy, Edinburgh University Press, 2009

Karla Mallette, The Kingdom of Sicily, 1100-1250: A Literary History, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005

Image

The Emperor Frederick meeting the Sultan Al Kamil in the handover of Jerusalem