Alessandro Manzoni and the Betrothed (I Promessi Sposi)

Alessandro Manzoni is a talented story teller and a perceptive observer of character. His novel, the Betrothed (I Promessi Sposi) has been celebrated as a gem of Italian literature ever since its publication. It is readily available as a physical, ebook or audiobook (see below) and several movie and serial versions have been made. The novel’s main characters, Renzo and Lucia are in love and they are to be married. Yet achieving this happy and unexceptional outcome turns out to be far from easy in Lombardy of the 1600s in which the historical novel is set.

Manzoni wrote his book in the early 1800s, two hundred years later, so we see a more distant past from a time that is already history for us. Manzoni’s time and the lives of Renzo and Lucia are linked. Lombardy is under “foreign” occupation in both the era of his characters and in Manzoni’s own lifetime. When he wrote the book, Lombardy was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. During Renzo and Lucia’s life, Lombardy is a Spanish colony. There are other less obvious links as we shall see.

A Wedding Denied

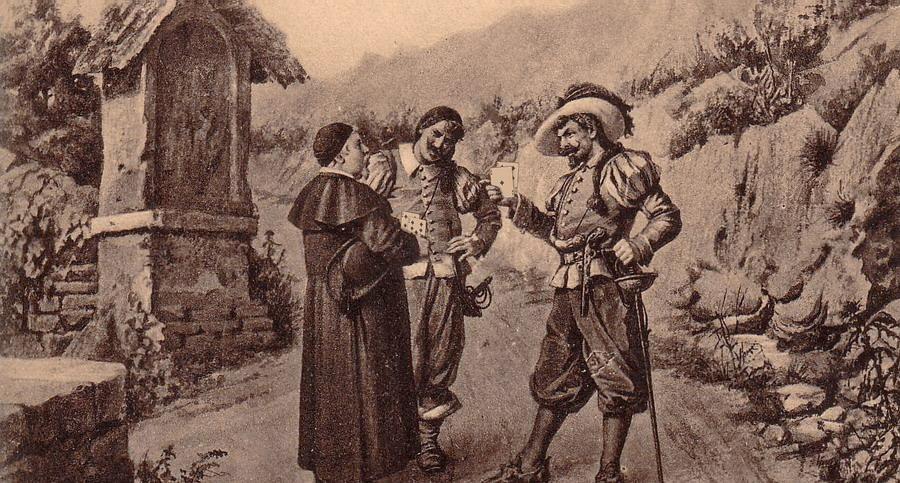

As the novel begins, Don Abbondio, Lucia and Renzo’s parish priest, has promised to marry Renzo and Lucia. The action starts one evening as Don Abbondio is walking home along a country lane. Two “bravi”, henchmen of the arrogant and dissolute Don Rodrigo accost the priest. Don Rodrigo is the local baron. He has plotted to seduce Lucia and will stop at nothing to have her. The henchmen make clear to Don Abbondio it will cost him his life should he marry the couple. Manzoni presents us not only with Don Abbondio’s words and actions, but his inner life and story (as Manzoni does for many of his characters). Don Abbondio is, as the narrative makes clear, entirely cowardly.

“Don Abbondio (our reader will have already discerned) was not born with the heart of a lion. From his earliest years, he was compelled to understand what a misfortune it was to be, in those times, a creature without claws or fangs, yet which feels disinclined to be devoured …Our Abbondio was neither noble nor wealthy and courageous, even less. He had thus realised, perhaps before reaching the age of discretion, of being, in that society, like a terracotta vessel compelled to travel crowded together with a host of iron jars.“

Don Abbondio (il lettore se n’è già avveduto) non era nato con un cuor di leone. Ma, fin da’ primi suoi anni, aveva dovuto comprendere che la peggior condizione, a que’ tempi, era quella d’un animale senza artigli e senza zanne, e che pure non si sentisse inclinazione d’esser divorato. … Il nostro Abbondio non nobile, non ricco, coraggioso ancor meno, s’era dunque accorto, prima quasi di toccar gli anni della discrezione, d’essere, in quella società, come un vaso di terra cotta, costretto a viaggiare in compagnia di molti vasi di ferro.

I Promessi Sposi, Chapter 1, Alessandro Manzoni, Mondadori Edition, 1985, own translation

To escape his dilemma (and the retribution that threatens him) Don Abbondio pretends to be ill and locks himself in his home. Lucia and Renzo’s efforts to entrap him into marrying them only results in disaster. With the help of the saintly Franciscan monk, Fra Cristoforo, they flee their village to escape Don Rodrigo. Lucia, accompanied by her mother, flees in one direction, and Renzo goes another. When they might see each other again or return to their homes they do not know.

As their adventures unfold, Manzoni weaves history, social commentary, theology and philosophy into the narrative. Lucia and Renzo struggle to come back together through civil unrest, invasions, exile and an outbreak of the plague. The story is a great read, but perhaps it is the incisive pen portraits of the inner life of its characters that most enriches the narrative.

Don Rodrigo and the Manzoni family

Don Rodrigo, as we have already seen, is essential to the story and his character is described in some detail. He is the unworthy heir of a once noble family. Manzoni describes for us his superbia and its antecedents.

“Don Rodrigo … paced up and down the hall in long strides. On the walls hung paintings of various generations of the family. When he found himself facing a wall, and turned, he would see before him a warrior ancestor glaring balefully at him, terror of his enemies and his soldiers, with short straight hair, his pointed moustache sticking out straight beyond his cheeks, with a slanting chin: standing heroically erect, armoured in shin guards, thigh guards, cuirass, brassards and gloves, all of steel. His right arm rested on his flank and his left on the hilt of his sword. Don Rodrigo gazed at him and when he arrived under the portrait, and turned, there was another ancestor: a judge, terror of litigants and lawyers, seated on a great seat covered in red velvet, robed in an ample black robe; entirely in black, except for a white collar, with two wide stripes, and turned with fur lining (it was the mark of a senator, which they only wore in winter, for which reason you would never find a painting of a senator dressed in summer gear); haggard, with frowning brows. In his hand he held an appeal, and he seemed to say “we’ll see”. Over here was a matron, terror to her maids; over there an abbott, terror to his monks. In short all persons who had inspired terror; as they still did even from the canvas. In the presence of these figures, Don Rodrigo’s torment was even greater. He was ashamed. He could not be at peace, that a mere monk had had the temerity to confront him with the arrogance of Nathan. He contemplated schemes for revenge, cast them aside, plotting how at the same time to satisfy his rage, as well as that which he called honour; …

“Don Rodrigo, … misurava innanzi e indietro, a passi lunghi, quella sala, dalle pareti della quale pendevano ritratti di famiglia, di varie generazioni. Quando si trovava col viso a una parete, e voltava, si vedeva in faccia un suo antenato guerriero, terrore de’ nemici e de’ suoi soldati, torvo nella guardatura, co’ capelli corti e ritti, co’ baffi tirati e a punta, che sporgevan dalle guance, col mento obliquo: ritto in piedi l’eroe, con le gambiere, co’ cosciali, con la corazza, co’ bracciali, co’ guanti, tutto di ferro; con la destra sul fianco, e la sinistra sul pomo della spada. Don Rodrigo lo guardava; e quando gli era arrivato sotto, e voltava, ecco in faccia un altro antenato, magistrato, terrore de’ litiganti e degli avvocati, a sedere sur una gran seggiola coperta di velluto rosso, ravvolto in un’ampia toga nera; tutto nero, fuorché un collare bianco, con due larghe facciole, e una fodera di zibellino arrovesciata (era il distintivo de’ senatori, e non lo portavan che l’inverno, ragion per cui non si troverà mai un ritratto di senatore vestito d’estate); macilento, con le ciglia aggrottate: teneva in mano una supplica, e pareva che dicesse: vedremo. Di qua una matrona, terrore delle sue cameriere; di là un abate, terrore de’ suoi monaci: tutta gente in somma che aveva fatto terrore, e lo spirava ancora dalle tele. Alla presenza di tali memorie, don Rodrigo tanto più s’arrovellava, si vergognava, non poteva darsi pace, che un frate avesse osato venirgli addosso, con la prosopopea di Nathan. Formava un disegno di vendetta, l’abbandonava, pensava come soddisfare insieme alla passione, e a ciò che chiamava onore; …

Manzoni, I Promessi Sposi, Chapter VII, own translation

As it turns out Don Rodrigo’s family and character was modelled on something Alessandro had before his own eyes: his own father and ancestors. For the Manzoni family were in fact the local dons in the vicinity of Lecco (where the novel is set).

“The Manzoni family were solid provincial squirearchy, land-owners, soldiers, merchants, and lawyers settled for some hundred and fifty years around Lecco on Lake Como … the … family had long had the reputation of being the terror of the district, a memory perhaps of the fearful Don Ercole Manzoni of a century before, … His ghost still rode the valley in the mid nineteenth century, and in 1850 was said to have killed a peasant with fright … ‘They say the old folk of family used, in feudal days to have a great dog to which, when it went through the village, the peasants were obliged to doff their hats and say: “My respects, my Lord Dog.”’

Archibald Colquhuon, Manzoni and His Times, pp 22-24

As Manzoni’s attitude to Don Rodrigo suggests, he did not get along with his father, and was thus happy to caricature the family’s forebears in the nefarious figure of Don Rodrigo.

Manzoni was thus born to wealth (to the extent that some incorrectly gave him the title “Count”; something Manzoni mocked when he heard it). Alessandro was born on 7 March 1785 to Don Pietro Manzoni and his mother was Donna Giulia Beccaria. Manzoni’s family background was, as it proved, his misfortune. His parents had an unhappy marriage which quickly broke down. Indeed Colqohuon notes the likely conclusion that Manzoni’s father was not Don Pietro at all, but a lover of his mother’s, Don Giovanni Verri. This is perhaps connected with Manzoni’s later attitude to his (at least) de jure father.

By 1792 the marriage was over and Manzoni himself had already been packed off to a miserable existence in a religious boarding school. In later years Manzoni was most enthusiastic about his maternal grandfather, Cesare Beccaria, who in the 1760s had been famed in French intellectual circles for his writings on penal reform which inspired the abolition of the death penalty in some jurisdictions and of torture in others.

Gertrude – the Nun of Monza

Another insightful pen portrait in The Betrothed, is that of Gertrude. Based on a historical person, she is the daughter of an illustrious and wealthy family. But, as for Manzoni himself, it is not a fortunate circumstance. Her story centres on the profoundly embedded custom of primogeniture. By this practice the wealthy families of Italy were continuously adding to the ranks of the disinherited and poor in order to ensure the family wealth was only passed to the first or eldest children. A related stratagem was to send children into the clergy, not only removing a drain on the inheritance, but providing the family with a potent source of influence in local or regional affairs (depending on the standing of the family).

Such was the case for Gertrude, the daughter of a Milanese Prince. From birth she was prepared for her fate, and given to understand that she was not of the same standing as the male firstborn.

“… Dolls dressed as nuns were the first toys that were placed in her hands, followed by little figurines representing sainted nuns; and such gifts were always accompanied by a counsel to keep them well in mind; how precious they were, and with that affirmative interrogative: aren’t they beautiful? – When the prince or the princess or the little prince (who of the boys was the only one raised at home) wished to praise the successes of the little girl, it seemed that they could find no better way of expressing their sentiments, but with the words: what a splendid Mother Superior! No one however directly said to her: you must become a nun. It was understood: an idea that was touched on incidentally in every discussion that bore on her future destiny.”

“… Bambole vestite da monaca furono i primi balocchi che le si diedero in mano; poi santini che rappresentavan monache; e que’ regali eran sempre accompagnati con gran raccomandazioni di tenerli ben di conto; come cosa preziosa, e con quell’interrogare affermativo: – bello eh? – Quando il principe, o la principessa o il principino, che solo de’ maschi veniva allevato in casa, volevano lodar l’aspetto prosperoso della fanciullina, pareva che non trovasser modo d’esprimer bene la loro idea, se non con le parole: – che madre badessa! – Nessuno però le disse mai direttamente: tu devi farti monaca. Era un’idea sottintesa e toccata incidentemente, in ogni discorso che riguardasse i suoi destini futuri.“

Despite such schooling, as a teenager Gertrude carried the wilful pride of her illustrious family. The monastic state envisaged for her was singularly unsuited to her character. As Manzoni unfolds the narrative we see her desperate struggles to evade her fate, as she comes to understand that it is not what she wants for herself. But we see also the webs in which her manipulative father has entrapped her, winding them ever tighter about her, until she herself publicly and forcefully proclaims her free wish to enter the nunnery (for it is sinful and contrary to church law for a family to compel a daughter into a nunnery).

As a nun, Gertrude retains her pride, but her life has become more and more embittered and turned to evil. She is surrounded by a monastic and spiritual life which is to her not the cause of peace, but a daily torment and reproach. We meet this tortured character as her life intersects Lucia’s.

It’s Not Plague!

Seventeenth century Milan, and Italy generally, suffered through one of its greatest outbreaks of the plague. It is something that Lucia and Renzo must survive if they are to come together again.

However, here again we see Manzoni’s concern with character, in this case public character. It is a story with resonances in our own times. Like the denials that today accompany climate change, many are invested in denial and confusion reigns. The result is an unresolved public controversy, until it is too late. Moreover denial was accompanied with potent conspiracy theories, all of which served to paralyse effective public action.

… what … causes astonishment, is the conduct of the people themselves, I mean to say, those the plague had yet to reach but which had every reason to fear it. As news arrived from towns so grievously afflicted, which formed a semi-circle around the city, and some of which were at a distance of no more than 18 or 20 miles, who would not anticipate that there would be a general movement, a desire for precautionary measures well or poorly executed, or at least a fruitless uneasiness? And yet, if the histories of that time are in agreement on one thing, it is that there was nothing of the kind. The scarcity of the preceding year, the oppressions of the armed forces and the afflictions of soul, seemed more than sufficient to explain the deaths. In public squares, shops, homes, whoever hazarded a word about the danger, who dared to raise the topic of the plague, would be met with astonished derision, with hot-tempered contempt. The same contempt, the same, to put it better, blindness and fixed opinion, prevailed in the Senate, in the Council of Decurions, and with every magistrate …

At the beginning then, not plague. Absolutely not. On no account. It was forbidden to even breathe the word. Then, pestilential fevers: the idea admitted indirectly by adjective. Then, not true plague, that is to say, yes it is a plague, but only in a certain sense, not true plague, but something similar that does not have its own name. Finally, plague without doubt and beyond question. But other ideas had already taken hold: poisoning and witchcraft, irremediably twisting and confounding the concept expressed by the word.

“… ciò che fa nascere … maraviglia, è la condotta della popolazione medesima, di quella, voglio dire, che, non tocca ancora dal contagio, aveva tanta ragion di temerlo. All’arrivo di quelle nuove de’ paesi che n’erano così malamente imbrattati, di paesi che formano intorno alla città quasi un semicircolo, in alcuni punti distante da essa non più di diciotto o venti miglia; chi non crederebbe che vi si suscitasse un movimento generale, un desiderio di precauzioni bene o male intese, almeno una sterile inquietudine? Eppure, se in qualche cosa le memorie di quel tempo vanno d’accordo, è nell’attestare che non ne fu nulla. La penuria dell’anno antecedente, le angherie della soldatesca, le afflizioni d’animo, parvero più che bastanti a render ragione della mortalità: sulle piazze, nelle botteghe, nelle case, chi buttasse là una parola del pericolo, chi motivasse peste, veniva accolto con beffe incredule, con disprezzo iracondo. La medesima miscredenza, la medesima, per dir meglio, cecità e fissazione prevaleva nel senato, nel Consiglio de’ decurioni, in ogni magistrato.

In principio dunque, non peste, assolutamente no, per nessun conto: proibito anche di proferire il vocabolo. Poi, febbri pestilenziali: l’idea s’ammette per isbieco in un aggettivo. Poi, non vera peste, vale a dire peste sì, ma in un certo senso; non peste proprio, ma una cosa alla quale non si sa trovare un altro nome. Finalmente, peste senza dubbio, e senza contrasto: ma già ci s’è attaccata un’altra idea, l’idea del venefizio e del malefizio, la quale altera e confonde l’idea espressa dalla parola che non si può più mandare indietro.”

Manzoni, I Promessi Sposi, Chapter XXXI, own translation

Alessandro Manzoni and the Italian Language

There is of course much more that could said about this entertaining and complex novel (and indeed many commentators have), however there is no substitute for actually reading it and so as not to diminish the pleasure of the reader who has not encountered it before, I will say no more about its plot.

Alessandro Manzoni wrote the novel in two major versions. The second edition, written in the 1840s introduces us to another major contribution that Alessandro Manzoni made during his lifetime.

Manzoni’s aspirations for his novel became aspirations for an Italian language reborn. He wished to reunite the written language (stilted and florid under centuries of formalism) with living spoken Italian, from which it had for so long been sundered. Faced with the many Italian dialects (indeed languages) spoken across the country, he settled on Tuscan as his preferred vehicle to embody this project. In its 1840s edition, I Promessi Sposi, was comprehensively reworked, including with the assistance and input of the Tuscan governess of his children, Emilia Luti. Like Dante’s La Commedia centuries before, Manzoni’s literary project became the proof of what was possible for the “living” Italian he imagined. The reworked text not only eliminated Milanese expressions, it removed archaic Tuscan usages which were no longer part of the spoken language of Tuscany. As Migliorini wrote:

” … the novel did much to achieve what Manzoni set out to do: to bring the written language nearer to the spoken and to deal a deadly blow to the rhetorical frills which for centuries had disfigured Italian literature.”

Bruno Migliorini, The Italian Language, translated by T. Gwynfor Griffith, p 364

Manzoni’s work was recognised across the Italian literary world. In the 1840s that literary world still spanned several countries, as Italy did not yet exist as a single polity. As early as 1806 Manzoni discussed the problem of the language, described Italian as “almost a … dead language”. His vision of every day spoken Tuscan as the next stage of Italian was inspired. However in “washing his clothes in the River Arno” (as he is widely quoted as saying), he was doing something slightly different than just adopting “living Tuscan”. His actual practice as much as his theory represented the future that emerged.

“I promessi sposi marked one of the last stages in the long-standing questione della lingua. … Manzoni was right in believing that a viable national language had to have its roots in real, practical linguistic usage and not in dusty old books or even dustier Academies. But, of course, his choice of Florence as the cradle of the new language was based on the cultural prestige Florentine usage had acquired in the fourteenth century, not on its standing in the nineteenth, which among the majority of non-Tuscan speakers was actually negligible. As Isaia Graziadio Ascoli, the father of Italian linguistics, predicted as early as 1873, the Florentine solution was bound to fail, and the national language emerged out of the growing linguistic contribution of all Italian regions to the national culture, fostered by educational and social improvements, and, in the present century, the spread of the mass media. Yet, while Manzoni’s linguistic engineering project failed, his novel was the greatest single contribution to the formation of a viable national language, the model for generations of educated Italians. That was because it paradoxically conformed more to Ascoli’s eclectic view than to Manzoni’s own normative position. After all it was not the work of a Florentine, but of a Milanese dialect speaker, whose second language was French, his third what he called parlar finito (a sort of Italianised Milanese), and his fourth a constantly evolving literary Italian, adapted almost day by day to its writer’s cultural needs. The power, beauty, luminous perfection of the definitive version are just as much the result of all the previous cultural and linguistic influences as of the final Florentinisation process.“

Manzoni and the Novel, Chapter 31, The Cambridge History of Italian Literature, p 437

Where to Find The Betrothed (I Promessi Sposi)

In English Penguin Classics publishes an edition translated by Bruce Penman. It is available as an ebook through various commercial outlets. A free ebook is available through Gutenberg as well as a Librivox audiobook.

In Italian, Liber Liber publishes a free ebook as well as a beautifully narrated italian audiobook.

Sources

Alessandro Manzoni, I Promessi Sposi, A Monadori 1985

Archibald Colquhoun, Manzoni and His Times a biography of het author of ‘The Betrothed’ (I Promessi Sposi), E.P. Dutton Inc, 1954

Bruno Migliorini, (T. Gwynfor Griffith transl.), The Italian Language, Faber and Faber, 1984

Luca Serianni and Pietro Trifone, Storia della lingua italiana, Volume primo – I luoghi di codificazione, Giulio Einaudi editore, 1993

Peter Brand and Lino Pertile, The Cambridge History of Italian Literature, chapter 31