Police Order Number 5: The Jewish Holocaust in Italy

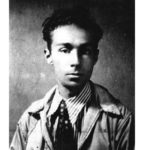

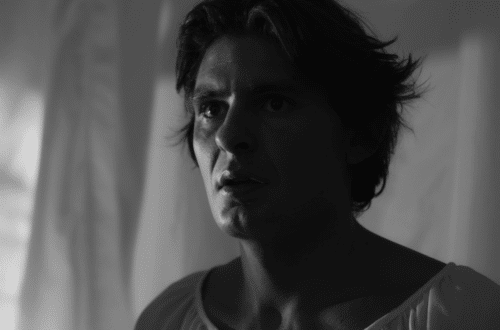

For years talk of race had been everywhere and step by step the path led towards the Jewish Holocaust in Italy. When, on 30 November 1943, Duffarini-Guido, Minister of the Interior placed his signature on Police Order Number 5, what was already a reality of oppressive persecution became an implacable machine of death. Primo Levi passed through that machine when it sent him to Auschwitz.

The War in Italy

On 9 July 1943 allied troops had landed in Sicily and by 3 September the invasion of the Italian mainland began. The same day Italy signed an armistice with the allies. The Grand Fascist Council had already lost faith in “Il Duce”, and imprisoned him on the Gran Sasso, the highest mountain in the Apennines.

But Italy’s surrender to the allies was Hitler’s signal and a German team was sent to rescue Mussolini and put him at the head of a new government of the Italian Social Republic.

Before the fighting was done in Italy, 70,000 Allied, 150,000 German and 40,000 Italian troops would die. Casualties would exceed a million and a half as the bitter fighting crept along the Italian peninsula. By December 1943 the allies had only advanced as far as Naples on the west and Ortona on the Adriatic coast. Jews trapped to the north within the Italian Social Republic were in every sense that mattered “behind enemy lines.”

Paradise Lost: Italian Jews and the Italian State

Even though Italy’s past had seen periodic outbreaks of anti-semitism stretching back to ancient times, when the Italian state was born in the 1860’s, few would have foreseen what was to happen to Italy’s Jews in World War 2.

In Saul Steinberg words, Italy was “their lost paradise”. In the impoverished area of Rome’s former Jewish ghetto, integration lagged behind but it was the exception. Across Italy intermarriage was high at an average of 43%; and in cities such as Trieste and Milan it reached the high 50s.

Newborn, the Italian state rejected the ignorance and prejudice of the past. The Jewish ghettoes were abolished across Italy and Jews welcomed as equal citizens. Indeed, Italy was one of the most favourable environments in Europe. Jews had been among the supporters and leaders of the Italian Risorgimento. Eight had been among Garibaldi’s Thousand who landed in Sicily, some were listed on the heroic registers of World War 1. Alessandro Fortis who had fought with Garibaldi in the wars of liberation became Italy’s first Jewish Prime Minister in 1905. In 1910, Luigi Luzzatti took office as Italy’s second Jewish Prime Minister. Such circumstances made what was to happen later even more horrific.

Even in the early years of the Fascist regime, Italy’s Jewish population of 46,000 (less than 1 in a thousand Italians) was not targeted as was to occur later. In the early years some were even members of the Fascist party. As late as 1932 Mussolini was quoted as trenchantly opposed to ideas of (biological) racism.

Of course there are no pure races left; not even the Jews … Race! It is a feeling, not a reality; ninety-five percent, at least, it is a feeling. Nothing will ever make me believe that biologically pure races can be shown to exist today. Amusingly enough, not one of those who have proclaimed the nobility of the Teutonic race was himself a Teuton … No such doctrine will ever find wide acceptance here in Italy … National pride has no need of the delirium of race … Anti-semitism does not exist in Italy … Italians of Jewish birth have shown themselves good citizens, and they fought bravely in the war. Many of them occupy leading position in the universities, in the army, in the banks. Quite a few of them are generals; General Modena is commandant of Sardinia.”

Mussolini quoted in Ivo Herzer, The Italian Refuge Rescue of the Jews During the Holocaust, p 36-37

However the statement was evasive and intended to deflect Emil Ludwig, a probing journalist who was enquiring into the absence of Jews in the Academy of Italy.

Although Mussolini’s regime had not (yet) introduced its own race laws, Mussolini had been prepared to use an anti-semitic dog whistle on numerous occasions in his climb to political power; as well as drawing on the concept of “racial hygiene”. In November 1919 Mussolini in a speech to Parliament stated: “I mean to say that Fascism has to deal with the race problem. The Fascists have to take care of the health of the race that will make history.” In part, Mussolini was able to reject “biological” racism because of an alternative “cultural” and “spiritual” theory of racism that was influential in Italy of the time.

The road to the Holocaust in Italy

In 1935, Italy invaded Ethiopia and issues of race now took on a new relevance as justification for imperial violence. As 1937 unfolded, anti-Jewish propaganda began to appear in Italian newspapers and pamphlets. The government was by October of that year already secretly working on anti-Jewish laws. Leading newspapers carried numerous stories about the “Jewish problem” in other countries.

By 1938, the paradise for Italy’s Jews began to collapse into nightmare. In July a comprehensive census was undertaken of the Jewish population. Also in July, ten Italian scientists sign a statement asserting Italian “racial purity” as a “scientific fact”. The Manifesto of Race referred to the “frequent talks of the leader on the matter of race”. It identified “orientals” and “africans” as “foreign” and dismissed the two century long Muslim era of Sicily as vanished. The Jews, however, were particularly targeted.

Gli ebrei non appartengono alla razza italiana … Gli ebrei rappresentano l’unica popolazione che non si è mai assimilata in Italia perché essa è costituita da elementi razziali non europei, diversi in modo assoluto dagli elementi che hanno dato origine agli Italiani.

The Jews do not belong to the Italian race … The Jews represent the sole population that has never assimilated itself in Italy because it is constituted of non-European racial elements, absolutely different to those of Italian origin.

The “defence of the race”. July 1938

Scientific nonsense became official dogma and lies became truth. From August 1938, “racist consciousness” was to be instilled in children from the earliest years of schooling. The stage was set and race laws, concerned particularly with the Jewish population, followed quickly.

Jews would no longer be welcome in the racialised education system. Under the Provisions for the Defence of the Race in Italian Schools, adopted from September to November of 1938 both Jewish teachers and pupils would be expelled. The press applauded the anti-Jewish measures, as they would generally continue to do, as the tragedy unfolded.

These initial measures were the beginning of a project with the goal of driving Italy’s Jewish citizens from their homeland. By November numerous measures had been taken including expelling Jews from military service, owning land, being employed as public servants at national, provincial or local level, from the Fascist party, and from universities. Even libraries were to be “purified” of “Jewish” materials.

Jews were also to be eliminated from the world of culture. Scientific and cultural academies, important in the Italian context, were purged of any Jewish members. Jews in Italy who were not Italian citizens were immediately interned or expelled.

Italy was entirely independent in its decision to begin this program of persecution and there is no basis to conclude that Italy’s actions were prompted by Germany.

Anti-Jewish propaganda was extensive. The Manifesto was published and distributed across Italy in various magazines and publications. La Difesa della Razza (the Defence of the Race), a popular science magazine, was distributed to schools, universities and libraries in large print runs. It was liberally illustrated with racist images. This and other publications were used to revive and propagate traditional vilification of Jews including blood libel, the poisoning of the wells, ritual murder, images of “white women” threatened by Jewish figures, economic exploitation, Jewish-communist conspiracy and other anti-Jewish tropes. One edition was entirely devoted to condemning race mixing and “half-breeds”.

The Myth of the Brava Gente

If Nazi Germany had not been so horrific, the myth of the Brava Gente “the good people” would likely never have been born.

The myth presented an image that only the Fascist regime was responsible for the persecution and that by and large Italians weren’t supportive of the policies. In its most inaccurate form, virtually all blame was deflected to Germany. Renzo de Felice’s 1961 groundbreaking study, although for the first time systematically telling the story of the persecution in Italy, suggested these kinds of conclusion.

The myth was propagated in mass media as well as through academic literature after the war. In 1986, the Nicola Caraccioli film The Courage and the Pity, promoted by myth. By 1988, an academic backlash began with writers now seeking to debunk what was clearly an inaccurate picture. More and more works have appeared attacking the myth and seeking to put the record straight.

Stories of Good

In part the family history of Jewish survivors themselves contributed to the myth, for there were stories of good.

Ivo Herzer, whose family was rescued in wartime Croatia by the Italian Army decades later organised a conference to honour the rescuers. His book records Josef Ithai’s childhood experiences of fleeing to Italy.

We waited quite nervously for the Italian border police to show up. … Two young, stern officers entered the car and demanded entry permits. In poor Italian, I explained that we had no papers, but that we were running from the Germans … At that point the two officers left abruptly without a word. … we saw a commotion and heard shouting at the station. Then a group of soldiers started running towards our car, carrying something in their hands.

“My God,” I thought, “what now? …” But the Italians began to throw candies and others sweets in the car. This kindness was almost beyond the endurance of our tense nerves. I saw the children with happy tears in their eyes, and the Italians shouted, “But why are they persecuting children? Why?” … “Have no fear … Everything is alright.” and it was the same from station to station. At each … there was a festive reception for us. We were celebrating the triumph of Jewish children. …”

Josef Ithai, The Children of Villa Emma: Rescue of the Last Youth Liyah Before the Second World War in Herzer (ed), The Italian Refuge … p 2

Alexander Stille, while noting the invalidity of the Brava Gente cliché felt it important to record his own family’s experiences.

My own father and aunt, who had grown up in Italy, were extremely reluctant to leave the country even though their position was extremely precarious. … Part of my family’s reluctance was the atmosphere of solidarity with which they were surrounded. My father recalled a Sunday afternoon shortly after the proclamation of the racial laws when the family received a completely unexpected visit from a family of farmers they knew from Formia, where my family had lived for a while and continued to visit during the summer.

These simple working people, who were hardly in the habit of visiting Rome, appeared on my grandparent’s door as it were the most natural thing in the world. They all sat down to tea and talked of various things. With a delicacy of soul worthy of the most refined aristocrats, my father said, the peasant family let my family know that if they should need help in the times to come, they could count on them.

Alexander Stille, The Double Bind of Italian Jews: Acceptance and Assimilation in Zimmerman (ed) Jews in Italy under Fascist and Nazi Rule, p 22

As the campaign against the Jews intensified in Italy, Fascist informers reported the doubts being expressed by some – why punish tens of thousands for the ill-deeds of a few ,went the talk.

As such records illustrate, the Brava Gente were real. But, as we shall see below, they were far from the full story.

Nonetheless, even the Fascist government in these years was not prepared to countenance (or enable) the German program of Jewish deportation, forced labour and extermination in areas it controlled. This is seen in the regime’s actions while it controlled a portion of Vichy France in 1942-43.

“It is not possible to permit the forcible transfer of the Jews,” said the Foreign Ministry. “The measures to protect the Jews, both foreign and Italian, must be taken exclusively by our organs.” [The Italians] immediately informed the Vichy authorities that they were “to annul every order of an anti-Jewish nature.” … Laval was so incensed at the italian interference that he called in the Italian ambassador to complain.

But the result was the opposite of what Laval had intended: the Italians promptly extended their protection of the Jews to include those in all the departments occupied by their forces … and the Italian Foreign Ministry notified Vichy … that only the Italians were entitled to arrest or intern Jews, irrespective of nationality, in the departments they controlled. …

… Calisse also warned the Vichy prefect that Italy would not permit the setting up of forced labor units in its zone. Only “Humane legislation” would be applied in the Italian sector, he said. … Colonel Mario Bodo, commandant of the carabinieri in Nice, posted his men outside the Jewish reception center and synagogue … to prevent Vichy police from going inside to make arrests …

If Vichy was outraged, the Nazis were aghast. …

John Bierman, How Italy Protected the Jews in the Occupied South of France, 1942-43, in Herzer (ed), The Italian Refuge, pp 219-220

Of course there was nothing “humane” about Italy’s own program of persecution, but not even appeals direct to Mussolini by German Foreign Minister von Ribbentrop, resulted in Italy permitting deportations (despite Mussolini’s promise that he would intervene). Later, the situation later changed.

Stories of Evil

Primo Zevi was one of those who saw the other side of the story. He was an employee in Italy. When the orders for expulsion came in 1938, he found no sympathy among his co-workers.

… Alle 9 di mattina, in ufficio, come annotato nel suo diario dell’epoca, “l’ispettore di Rovigo mi veniva a dire che dovevo allontanarmi subito, perché licenziato. Dopo 12 anni circa di lavoro, via! … come un furfante, un ladro.”

… at 9 in the morning, at the office, as was noted in his diary for the day, “The inspector from Rovigo came to tell me that I had to leave quickly, because I was fired. After about 12 years of work, get lost! … like a fraudster, a thief.”

Mario Avagliano and Marco Palmieri Di Pura Razza Italiana …p 53

Eugenia Bassani and Gian Paolo Minerbi recalled being abandoned by friends and colleagues after being expelled from school. Giacoma Limentani recalled being expelled with added cruelty by a Fascist teacher.

… non solo non mi frequentavo piu, ma neanche mi salutavano più se mi incontravano per strada … quasi tutti i ragazzi della mia classe non mi salutavano più, cambiavano marciapiede quando mi vedevano per strada … “Fuori di classe, brutta ebrea,” … nessuna compagna di scuola … si è fatta viva per dire “Come mi dispiace!” Se ne fregavano …

… not only did they not visit me any more, they would not even greet me if they saw me in the street … almost all the children in my class no longer greeted me, they would cross to the other sidewalk when they saw me walking in the street … “Get out of the class, you ugly Jew” … none of my friends … came to tell me how sorry they were. They don’t give a damn …

Mario Avagliano and Marco Palmieri Di Pura Razza Italiana …p 14

As the program of persecution progressed, indifference and aversion began to transmute to active hate as Avagliano and Palmieri record.

Nei luoghi pubblici e sui mezzi di trasporto i commenti antisemiti sprecano, come il signore che su un tram romano, battendo la mano sul copertina di una rivista con imagine deformati esclama, “Ecco, si vede che sono una razza inferiore, segnati da Dio, guardate che mostruosità.”

In public places and on public transport, anti-semitic comments spread, like a man who on a tram in Rome, slapping his hand on the cover of a magazine with a deformed caricature exclaimed, “Look, you can tell that they are an inferior race, marked by God, what monstrosity.”

Mario Avagliano and Marco Palmieri Di Pura Razza Italiana …p 24

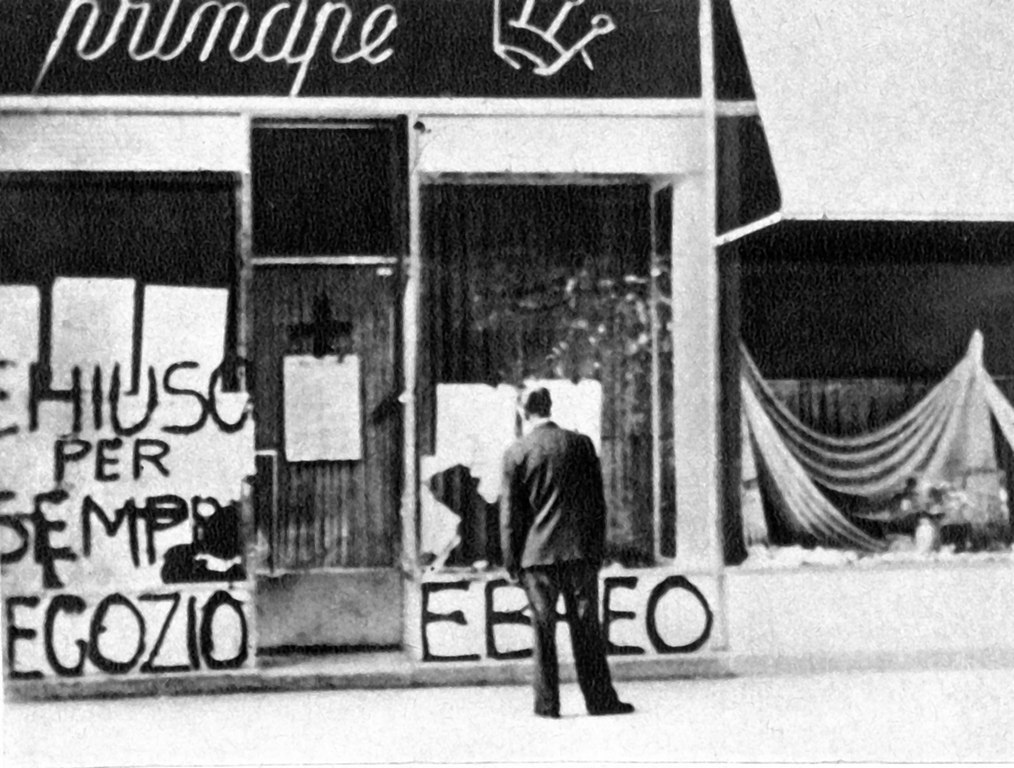

The impacts of such economic and social exclusion were severe. Even the poorest peddlers were impacted when their licences were revoked in 1941.

At present, I am without work and my family is suffering enormously, especially the children who are being deprived of the most basic necessities. I have a disabled child who needs special care … Since this is a very sad case of an extremely poor family, I beg you, Your Excellency, to show some interest [in our case]. Otherwise, during the winter, we will have to sleep on the street because of the lack of money for rent.

Iael Nidam-Orvieto, The Impact of Anti-Jewish Legislation on Everyday Life and the Response of Italian Jews, 1938-193 in Zimmerman, Jews in Italy under Fascist and Nazi Rule, p 161

Veterans were expelled from veteran organisations.

You see, today they forbid me the honor of wearing the blue string. This was the last symbolic tie with my comrades from the war of independence … They denied me even this spiritual bond and the promise is broken …

Iael Nidam-Orvieto, The Impact of Anti-Jewish Legislation on Everyday Life and the Response of Italian Jews, 1938-193 in Zimmerman, Jews in Italy under Fascist and Nazi Rule, p 164

Universities failed to take effective action to oppose the persecution. They had already submitted to the requirement imposed in 1931 to swear allegiance not only to king and country but to the Fascist regime. When the expulsion of their Jewish colleagues arrived, little was done. Vita Universitaria, the official journal of Italian universities objected the expulsion of Jewish professors on the grounds that the positions could not be filled with qualified people for years to come and it was better for the posts to be left vacant. But this was a rare instance of a public voice raised against the policy. The Jewish victims of the ban reported expressions of solidarity from colleagues, but only in private. Publicly there was largely silence. In practice, the positions from which Jews were expelled were filled by their non-Jewish colleagues.

The approaching tragedy of the holocaust was also preceded by an increasing climate of violence and hatred. An example was a pamphlet that which carried abuse: “vampires”, “blood suckers”, “hate them like we hate the plague”, “exterminate the Jews”.

Acts of violence were carried out by Fascist squads and ordinary citizens. These acts included beatings and attacks on Jewish shops and locations.

An important factor in the holocaust that was to come, was the network of spies and informers who sent information to the Fascist secret police from across Italy. Some were paid “professionals”. Others were profiteers who saw an opportunity to obtain the property or position of their Jewish neighbours. Others were motivated by hatred or fanatical zeal. The uncounted denunciations and reports that arrived from across Italy are still there in the archives and are an important part of the raw material of today’s academic study.

The Italian Social Republic 1943 – 1945 the Jewish Holocaust in Italy begins

After the establishment of the Italian Social Republic in 1943, what was already terrible, became much worse. Over 32,000 Jews found themselves within the boundaries of the regime. By the end of September 1943, the German authorities began rounding up Jews in Italy, with special teams sent to Italy for the purpose. In December the new Italian regime adopted its own round up policy.

Italy and Germany … entered a sort of competition as to who should have the right to round up, imprison, and intern Jews.

Liliana Picciotto, The Shoah in Italy: Its History and Characteristics in Zimmerman (ed), Jews in Italy under Fascist and Nazi Rule, p 209

The fact that Italy had in place a systematic program of persecution and propaganda against the Jewish population allowed the program of internment to start immediately. The preparatory steps that were used in some other countries were not needed. The Germans quickly rolled out a system of SS and police, including in north-east Italy was was under direct German administration.

On October 16, 1020 people were rounded up in the former Jewish Ghetto in Rome. The Jews in Rome believed their close proximity to the Vatican would protect them. It did not.

They were sent to Auschwitz. All but 196 of them, were sent immediately to the gas chambers. Only 17 ever returned. The Germans had intended to start in Naples, but a popular uprising had driven them out of the city before it could be implemented.

The “Judenaktion” raid in Rome was quickly followed by similar raids in cities across northern Italy: Milan and Florence among them. As the Germans were few and scattered they called on the assistance of Italian police to implement the roundups.

Police Order Number 5 – Complicity in the Holocaust in Italy

However the new Italian regime was still coming to grips with its new reality as a power subordinate to Germany. It was not able to give attention immediately to the “Jewish question”. But by November it did so. The regime declared all Jews “enemy nationals”. On 30 November 1943, Police Order 5 was signed.

From 1 December, when the order was sent to provincial governors, every Italian Jew was a hunted person. In the following months, provincial police were sent to carry out house-to-house searches. The Italian police already knew where to find the Jews. Several ministries were involved in the work.

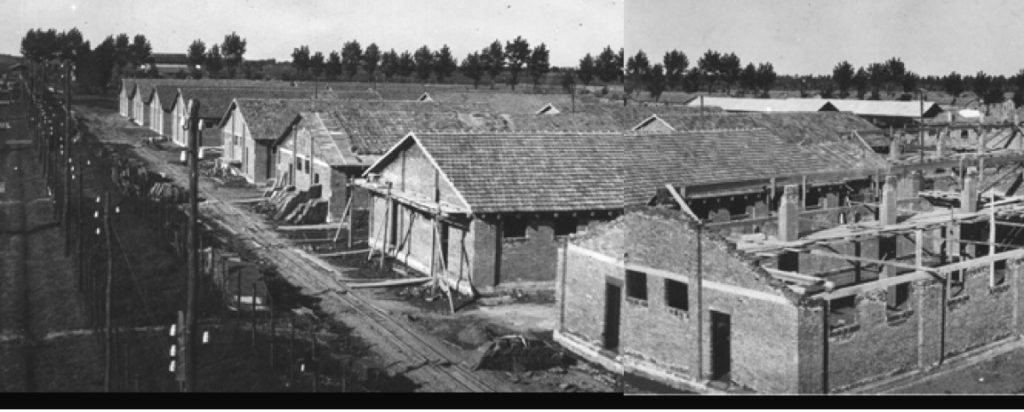

The new laws, reproduced in translation below, ordered the internment of all Jews in preparation for their being sent to special purpose concentration camps.

It is also clear that the Italian government already knew that Jews sent north were intended for extermination. Further, as the text of Police Order No 5 makes clear, it was an opportunity for the regime to confiscate Jewish properties for its own use.

Concentration camps were set up across northern Italy. A former prisoner of war camp at Fossoli di Carpi was converted as an internment camp. It was a major internment centre and from February 1944 deportations began in collaboration with the Germans who were present at the camp. By August 1944 four more transports had been organised.

In areas directly controlled by the Germans similar deportations were occurring.

Before it was over, the Holocaust in Italy took 8529 Jews. Almost 7000 were deported. Hundreds died in detention in Italy. Almost 1000 were still missing by the end of World War II.

Acts of Resistance

While the record of involvement and collaboration in the Holocaust is clear and extensive, not all Italians were content to let their Jewish neighbours be exterminated. When the roundup in Rome happened, the government was silent. Some resisted. Some hid neighbours. Taxi drivers spirited Jews away. Crowds attempted to gather around already arrested individuals so they could escape. Some churches offered refuge. The German authorities noticed.

The attitude of the Italian population has been characterized by clear symptoms of resistance which in many cases has even developed into active aid … Even in the moments when the German police forces were breaking into homes, clear and in many cases successful attempts to hide Jews in adjacent apartments were noted. The anti-Semitic part of the population was not noticed during the action, while, on the contrary, an amorphous mass which, in individual cases, even tried to separate the police from the Jews, was observed.

Report of German officer quoted Liliana Picciotto Fargon, The Jews During the German Occupation and the Italian Social Republic, in , p 122

Among those who resisted were Italian officials who found various ways of impeding or frustrating deportation efforts that followed. While they were the exception, their existence is important. Among them was a sergeant of a police station in Verona who warned victims of their impending arrest, which he was responsible for carrying out. In Modena senior police officials hid Jews in a convalescent home. The town hall “lost” records. In another town bus drivers sabotaged their buses, so that they could not be used to transport Jews to internment centres.

Conclusion

Undoubtedly, Italy’s own program of Jewish persecution during the Fascist era and its involvement in the Holocaust is one of the darkest periods of Italy’s long history. There are others. It is of course of critical importance that such history is not forgotten, and is to the best of our ability, recounted accurately.

Text of Police Order Number 5

Translation of Police Order Number 5

Cabinet of the Ministry of the Interior

Highest Priority 1/12/1943

To the heads of all provinces

No. 5. The following police order is communicated, for immediate execution in the entire territory of that province :

First: all the Jews, even if previously exempt, of whatever nationality they may be, who are resident in the national territory must be sent to designated concentration camps. All their properties, fixed and mobile must be immediately sequestered, in anticipation of their confiscation for the benefit of the Italian Social Republic, who will apply them to the benefit of those displaced by enemy air raids.

Second: all those born of mixed marriages, in application of the Italian racial laws currently in effect, are recognised as belonging to the Arian race and must be subject to special police surveillance.

In the meantime Jews will be gathered in provincial concentration camps in preparation for being place together in specially equipped and designated concentration camps.

The Minister, Buffarini-Guido

Sources for Police Order Number 5 – the Jewish Holocaust in Italy

Mario Avagliano and Marco Palmieri, Di Pura Razza Italiana L’Italia “Ariana” di fronte alle leggi razziali, Baldini & Castoldi, 2013

Renzo de Felice, Storia degli ebrei italiani sotto il fascismo, Einaudi, 1961

Robert S.C. Gordon, The Holocaust in Italian Culture 1944-2010, Stanford University Press, 2012

Shira Klein, Italy’s Jews from Emancipation to Fascism, Cambridge University Press, 2018

Ivo Herzer, Klaus Voigt and James Burgwyn, The Italian Refuge Rescue of the Jews during the Holocaust, The Catholic University of America Press, 1989

The Jewish Virtual Library, The Defence of the Race

Joshua D. Zimmerman (ed), Jews in Italy under Fascist and Nazi Rule 1922-1945, Cambridge University Press, 2005