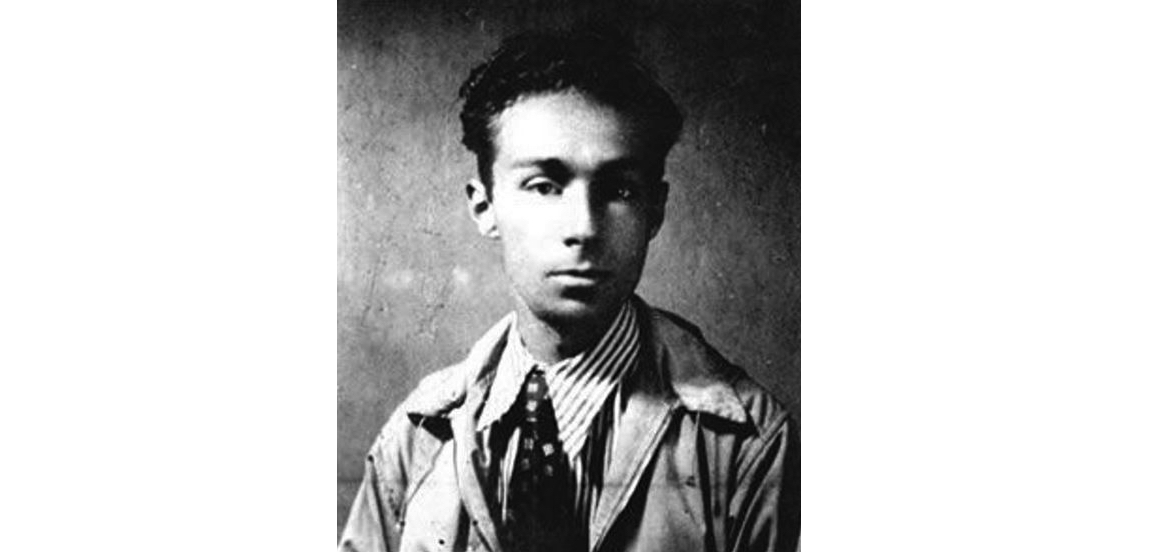

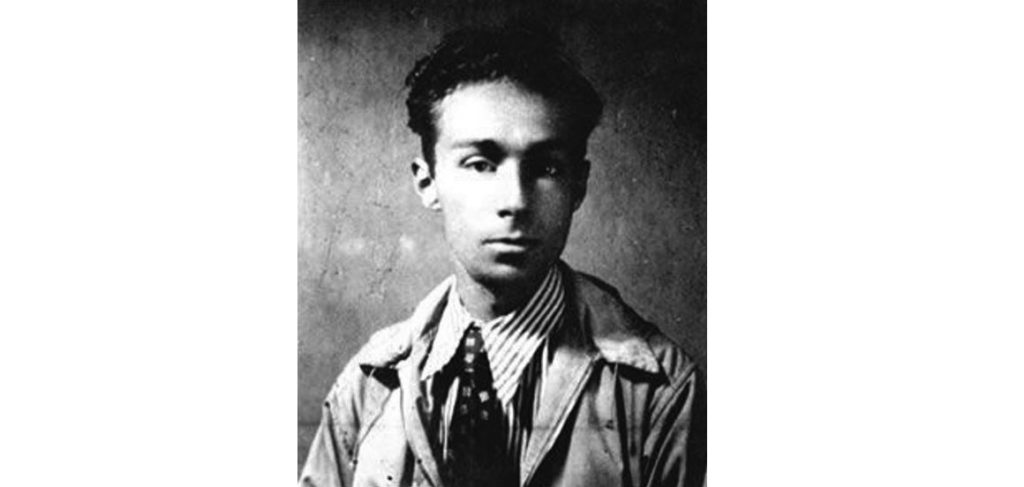

Primo Levi Zinc and the Pure Race

There is a place so deep in hell that Virgil could not bear to show it to Dante. Science, in unholy coupling with prejudice, indifference and self-interest, discovered it in our own times: and called it Auschwitz. Primo Levi, an Italian Jew, passed through that hell, and survived. Although, until Fascism made of him a thing to be exterminated, Levi hadn’t given any importance to his Jewishness.

Zinc is a short story of Primo as a young chemistry student. Like countless young men before him he meets a girl: Rita, and shares the exhilaration of the first faltering steps of getting to know her. It could be the story of any young couple, except as his world begins to tell him, he is different.

But for now he is just a chemistry student and his crises and victories are those of the first day of a new lab, when his task is to work with Zinc: a “boring” and “colourless” metal. The task is simple: combine zinc with diluted sulfuric acid. But Zinc has a strange property, when it is pure, it refuses to combine with other chemicals. The slightly impure kind is needed to make it useful. Purity was to Levi disgustingly moralistic; but that impurity was life.

In order for the wheel of life to turn, for life to be lived, impurities are needed … because I too am Jewish, and she is not: I am the impurity that makes the zinc react …

Primo Levi, The Periodic Table, p 36, 37

It was during that month that the madness of racism tightened its grip on Italy. In that month that Primo came to know that he was to be considered an impurity. Something that had been of little importance to him at a personal level now marked out the path, that step by step would take him to Auschwitz.

In July and August of 1938 a racial manifesto was published in Italian newspapers. This manifesto claimed that races were biologically “real” (something science has now categorically refuted). But the manifesto was not done. It claimed that Italians were a “pure race” and that the “ancient purity of Italian blood” was “the greatest title of nobility of the Italian Nation”.

The vacuity of such science is evident if we recall that it was only a handful of decades since Italy had existed at all as a country. At the time one of the Risorgimento politicians, Massimo d’Azeglio had famously stated: “Now that we have made Italy, we must make Italians.” With sleight of hand, an invented people had become an eternal pure substance.

This manifesto was signed, not by the ignorant, the anafabeti, as they were long called in Italy; but by the learned. Holders of high academic and scientific positions. Ten among Italy’s learned men of medicine, anthropology, neuropsychiatry, pediatrics, endocrinology, zoology, demography and physiology and biology signed.

With the canonization of this new orthodoxy, worse quickly followed. Doctrine would now be followed by law. In September 1938, law authorised the expulsion of Jewish teachers and children of Jewish background from schools. Worse was to come. Much worse.

In the hell it created for Primo there was no “castle of the learned” as we find in Dante’s Limbo. The learned who fashioned this hell for their fellow human beings did not descend into it; unless they were victims themselves. It was a hell in which human ashes were spread to make paths for those who were yet living.

Images

A young Primo Levi.

Sources and Notes

31 July 2019 marked the centenary of Primo Levi’s birth. He is remembered as a great Italian writer.

Primo Levi, The Periodic Table (see archive)

Mario Avigliano and Marco Palmieri, Di Pura Razza Italiana

See also Dante among the dead men (discusses Dante’s influence on Levi) https://www.jstor.org/stable/3195249?seq=10#metadata_info_tab_contents