Italy’s Rapunzel, Cinderella and other Italian Fairy Tales

The first European collection of Fairy Tales, the Tale of Tales was written in Naples in 1630. It tells such well-known stories as Rapunzel (Petrosinella – or Little Parsley) and Cinderella (La Gatta Cenerentola). Giambattista Basile wrote the Tale of Tales (also known as the Pentamerone) in Neapolitan rather than standard Italian. It was the first book of children’s fairy stories published in Europe and arguably gave birth to the written genre that we know today, although the spoken tradition is much older.

Basile’s book is a who’s who of fairy tale characters we know today. As well as Rapunzel and Cinderella (La Gatta Cenerentola) the story of Snow White, Sleeping Beauty (Sola, Luna e Talia), and Puss in Boots (Pippo) are all told in this book. It’s no accident that we know such stories, as they eventually (via France) found their way into Grimm’s fairy tales and ultimately to us. The Grimm brothers knew and admired Basile’s work and published a German translation of the Tale of Tales and its 50 stories told over five days.

Did the fairy tales follow a written or spoken path?

The scholar Ruth Bottigheimer in her History of Fairy Tales, argues for a primarily written origin of fairy tales on the basis of this kind of genealogy.

The Grimm’s brothers believed that the stories the middle class girls they knew told them were part of an authentic oral tradition. However the girls heard them, literate Protestant Germany absorbed them from French writers. These French versions had in turn had been taken from the older written sources in Italy, in particular Basile’s Tale of Tales (also known as Pentamerone) and the even older works of the Giovan Francesco Straparola whose Pleasant Nights (Venice, 1551) told a variety of stories including fairy tales, some of which were also drawn on in Basile’s collection.

However, even Basile and Straparola were not the original tellers of these stories. For they were not primarily inventors of stories, but collectors and raconteurs, modifying the stories they took from others for their own tastes and audiences. If later authors found them too bawdy or brutal, they would change them again.

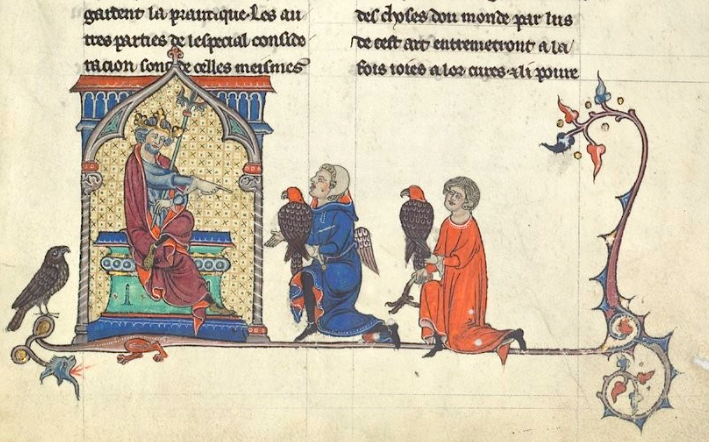

This recycling of stories wasn’t in itself new. Boccaccio’s Decameron (written centuries before) which was also a collection of reworked stories and the even older A Thousand and One Nights written in 9th century Baghdad had a similar pattern.

The existence of medieval and even ancient examples of very similar tales supports a conclusion that the stories might be much older. Versions of Cinderella shows up in a 9th century story in China and in ancient Greek versions. The most ancient version known appears in Sumerian stories of the Goddess Inanna who has some adventures which parallel those of Basile’s Cenerentola (Cinderella).

Scholars point out that among reasons the “folk” and fairy tale idea became so popular from the 19th century was that it was connected with the invention of the idea of “nations”. Having a collection of “ancient” tales for each folk (supposedly transmitted down the ages largely unchanged) fitted with the myths the new nation-states needed to create. Thus, Grimm’s fairy tales attracted state support in the strengthening Prussian state.

The Oral Tradition

The theory of a purely written tradition is unlikely. Storytelling is undoubtedly much older than the invention of writing. The relationship between the oral “stories of the people” and written works (and their influence on each other) is much debated.

Dante understood the importance of the common tongue. When we read the works of Dante, it is easy to forget that they too are linked to the oral tradition. Dante’s Inferno was in part inspired by Virgil’s Aeneid, which in turn was inspired by Homer’s Odyssey. It was hundreds of years before anyone wrote it down. In other words, the Inferno is only one degree of separation from the older oral tradition.

Further, in Dante’s time, his works were primarily sung and heard on street corners rather than read. This was particularly so because of the cost of handwritten manuscripts. Only after the invention of the printing press did books become widely available.

Despite Dante’s views, formal written Italian after Pietro Bembo applied his strictures to it, became for centuries a language distant from the people. It was a special preserve of a small minority who treated it like a new Latin. A gulf opened between the written and the oral. The latter was the domain of Italy’s many spoken dialects. Italian almost exclusively read, rather than spoken.

The oral tradition, referred to dismissively as old wives tales, even in ancient times, represents an older but continuing oral storytelling tradition. Women were the primary storytellers; and children their audience. Like the equally dismissive term “crafts” instead of “art” for the creative genius of women and the poorer classes, it took a long time before we began to think of fairy tales as literature.

Italian Fairy Tales in Carlo Levi’s Christ Stopped at Eboli

Carlo Levi’s Cristo se Fermato a Eboli, provides us with a fascinating window into the rich oral tradition of story-telling of everyday life in rural Italy in the 1930s.

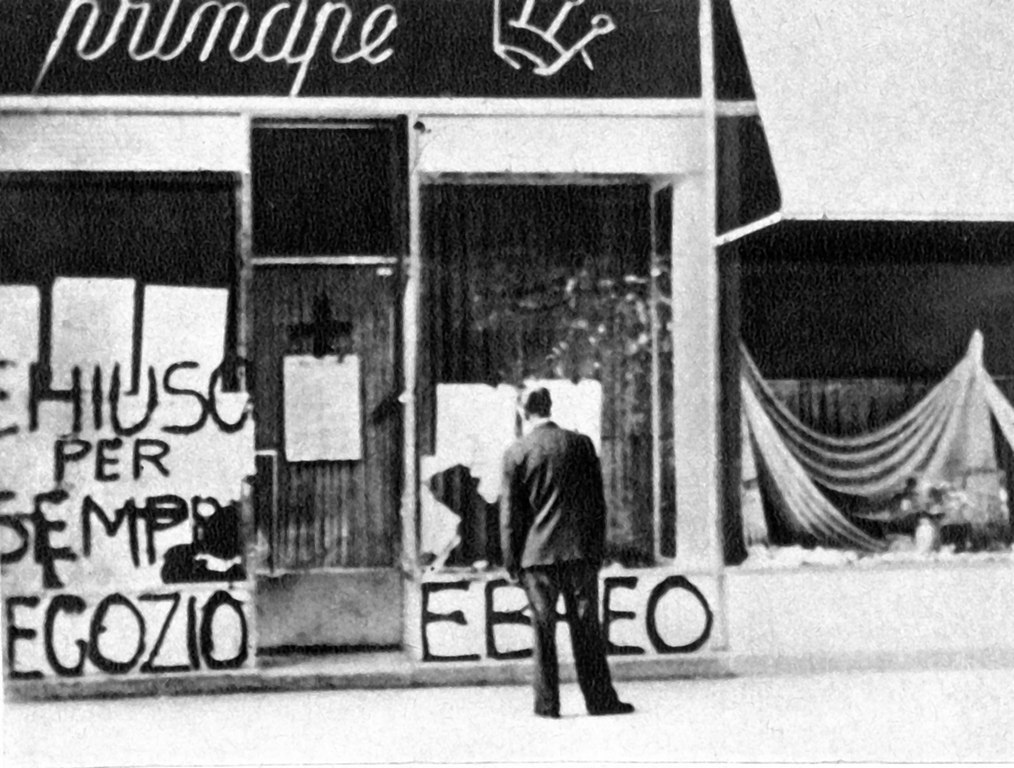

The government, in the years of Fascism, had exiled Levi, a city northerner from Turin, to a southern village in a barren mountainous wasteland. The local contadini, the farmers, are mysterious to him. As Levi’s writing makes clear they live a way of life almost entirely separated from the literate culture of which Levi is a part. They experience Levi’s world as oppressive, brutal and exploitative. Levi in turn experiences the farmers of the land as belonging to a different culture. For them, the government is a distant and hostile force of nature.

Levi’s accounts of the “superstitions” of the people around him hint at the richness of their stories. Witches (streghe), spells and folk medicine (incantesimi), sprites and gnomes (monachicchi, gnomi or folletti) the kinds of creatures that appear in fairy tales, are the givens of life.

The gnomes are tiny, airy creatures that run hither and yon; their greatest delight is to tease good Christian souls. They tickle the feet of those who are sleeping, pull sheets off the beds, throw sand into people’s eyes, upset wine glasses, hide in draughts of air so as to blow papers about, and make wet clothes fall off the line into the dirt, pull chairs out from under women, hide things in out-of-the-way places, curdle milk, pinch, pull hair, buzz and sting like mosquitoes. But they are innocent sprites, their mischief is never serious but always in the guise of a joke; however annoying they may be, they never cause serious harm. Their character is capricious and playful and it is almost impossible to lay hands on them. On their heads they wear a red hood that is bigger than they are and woe unto them if it is lost; they weep and are quite disconsolate until they have found it.

The only way to ward off their tricks is to seize them by the hood and if you can take it away from them, they will throw themselves at your feet in tears and implore you to give it back. Beneath their whimsicality and childish playfulness the gnomes are very wise; they know everything below the surface of the earth and, of course, the location of buried treasure. In order to recover his red hood, without which he cannot live, a gnome will promise to tell you where a treasure is hidden. But you must not give him back his hood until he has led you to it; as long as the hood is yours the gnome will serve you, but if he can lay hands on it he will leap away, mocking and jumping for joy, and he will not keep his promise.

Carlo Levi. Christ Stopped At Eboli The Story Of A Year

The similarity of these highland gnomes to the leprechauns of Ireland is striking. It suggests an ancient and common oral tradition from which they are drawn. Alternatively, such stories travelled easily in the spoken word.

Italian Fairytales arrive late on the scene

Despite the early appearance of Lo Cunto de li Cunto and The Pleasant Nights, the first comprehensive collection of Italian fairy tales did not appear until 1956.

In that year Italo Calvino’s collection of 200 Italian fairy tales was published. It is a beautifully illustrated book, with Italian fairy tales from all over Italy. As might be expected Calvino draws on Basile’s and Straparola’s collections, and the old favourites are there. But Calvino brings together a much richer set of stories.

It is curious that it took so long for Italy to “find” its fairy tales. Unlike in Germany, Calvino created his collection long after Italy was created. Calvino notes the existence of regional collections made before him. Among these are the enormous Sicilian Fairy tale collection by Giuseppe Pitrè or collections of Tuscan fairy tales. Calvino’s is the first that brings these various sources together in a single national collection.

Sicilian story tellers and Calvino’s world of fairy tales

Calvino takes the trouble to record Pitrè’s recollections of his most important source. She was an illiterate old woman, Atatuzza Messia (who had formerly worked for Pitrè family as a domestic).

She is far from beautiful, but is glib and eloquent, she has an appealing way of speaking, which makes one aware of her extraordinary memory and talent. Messia is in her seventies, is a mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother; as a little girl she heard stories from her grandmother, whose own mother had told them, having herself heard countless stories from one of her grandfathers. She had a good memory so never forgot them. … Her friends in Borgo thought her a born storyteller; the more she talked, the more they wanted to list.

Messia can’t read, but she knows a lot of things others don’t … If the setting of the story is aboard a ship due to sail, she speaks, apparently unconsciously, with nautical terms and turns of phrase characteristic of sailors … If the heroine of a story turns up penniless and woebegone at the house of a baker, Messia’s language adapts itself so well to that situation that one can she her kneading the dough and baking the bread — which in Palermo is only done by professional bakers. …

Messia saw me come into the world and held me in her arms; this is how I heard from her lips the many beautiful stories that bear her imprint. She repeated to the young man the tales she had told the child thirty years before …

cited in Italo Calvino, (George Martin, trans) (1956, 1980) Italian Folktales Selected and Retold, p xxiii

Calvino speaks of the experience of entering for two years the strange magical world of fairytales.

… during those two years the world about me gradually took on the attributes of fairyland … in the lives of peoples and nations, snake pits opened up and were transformed into rivers of milk; kings who had been thought kindly turned out to be brutal parents; silent, bewitched kingdoms suddenly came back to life. I had the impression that the lost rules which govern the world of folklore were tumbling out of the magic box I had opened … Now that the book is finished, I know that this was not a hallucination … but the confirmation of something I already suspected — the folktales are real.

Italo Calvino, (George Martin, trans) (1956, 1980) Italian Folktales Selected and Retold, p xviii

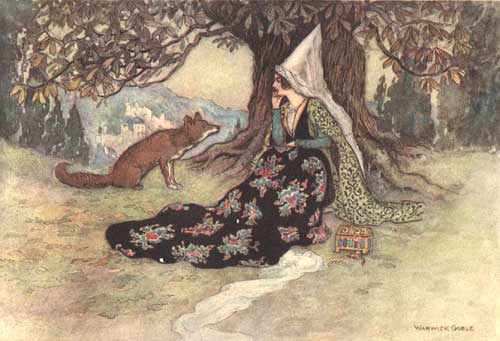

Images

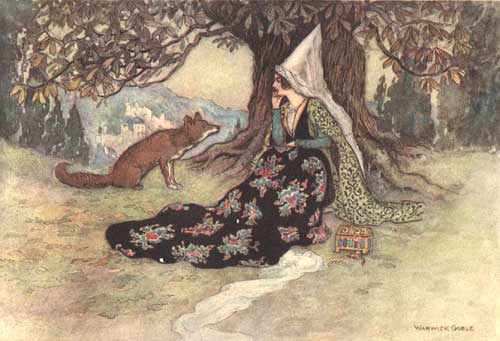

“Parsley” – or Petrosinella. Illustration from an 1846 translation of Lo Cunti de li Cunti. 1850

Sources

Graham Anderson (2000), Fairytales in the Ancient World, Routledge

Basile, Giambattista, (ca. 1575-1632.), Giambattista Basile’s The tale of tales, or, Entertainment for little ones Detroit : Wayne State University Press

Bottigheimer, Ruth B. (2009) Fairy tales a new history Albany, N.Y. : Excelsior Editions/State University of New York Press

Italo Calvino, (George Martin, trans) (1956, 1980) Italian Folktales Selected and Retold, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Inc, London

Ziolkowski, Jan M, Fairy tales from before fairy tales the medieval Latin past of wonderful lies (2009) Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press