Which came first: pasta or noodles?

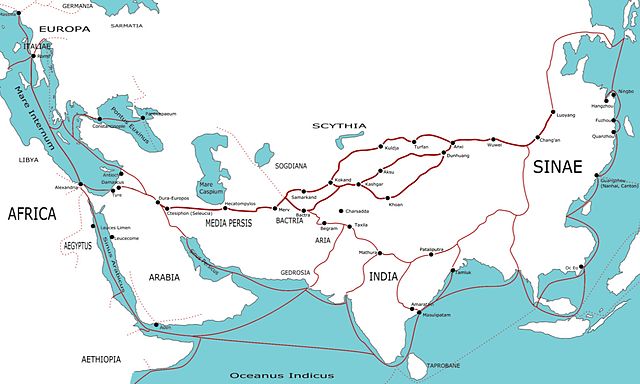

Plot spoiler. Its noodles. Lovers of Italy, doff your cap to China! … Well, at least that’s how I was going to start this article. That was before I started reading Jen Lin-Liu’s delightful book: On the Noodle Road. She’s not so sure the story is that simple. Like Marco Polo, she travels the Silk Road, but in reverse. She is on a 21st century quest to trace the journey of noodle from East to West. No one more determined could be imagined. And, her quest is personal.

Travelling through cultures that straddled East and West, I figured, might reconcile what I’d felt were opposing forces in my life; maybe I’d find others who relate to my struggle. …

Jen Len-Liu, On the Noodle Road: From Beijing to Rome with love … a true story, Allen & Unwin, 2013, p 14

In the same way that the tomato became inseparable from Italian cuisine, there is a lot more to say. Of course, the dishes associated with both pasta and noodles are incredibly diverse (and delicious). Both, also, have become global foods eaten around the world. Jen Lin-Liu’s notes the similarity of a variety of shapes. Cat’s ears noodles and orecchiette are similar. Wantons and ravioli are the same idea. Hand pulled noodles and angel hair end up as similar products. However, some Italian flavours also remind her of China. Parmigiano reggiano over pasta evokes for her umami. Olive oil and vinegar reminds her of the flavours of sesame oil and black vinegar. Of course each food culture also has its own unique creations that we can only truly appreciate by eating them. Both cuisines are what the Italians call “cucina povera”: best as rustic home-cooked foods.

The Case of the Ghost Noodles of Lajia

Before we begin the journey ourselves, what is the evidence that noodles were around before pasta? As it turns out in 2005, archeologists unearthed a 4000 year old bowl of noodles in north-west China at the archeological site of Lajia. This sets anyone wanting to argue that pasta came first, a pretty high bar to leap. In Lajia, which some have compared to Pompeii, people are captured in the instant that an ancient disaster swept over them. In Lajia’s case a massive mud-slide buried the people of Lajia, entombing them until discovered by archeologists thousands of years later. Jen Lin-Liu met Lu Houyan, a scientist involved, and quotes his simple (if qualified conclusion).

I can’t say for sure that the Chinese were responsible for bringing noodles to the West, but I can be very sure that no one will find a noodle that’s older than this.

Lu Houyan, cited in Jen Len-Liu, On the Noodle Road: From Beijing to Rome with love … a true story, Allen & Unwin, 2013, p 14

He concludes that the Lajia noodles are of millet flour (rather than the durum wheat of pasta). Likely, a kind of dough press was used to make them. Well that’s it then. Case closed.

Not so fast. We are a long way from showing that noodles travelled from East to West. For one thing, pasta is made of durum wheat. Wheat isn’t native to China (or Italy for that matter). It only arrived in China’s heartland long after the disaster in Lajia. Wheat comes from the Middle East. There it was first cultivated and from there it spread west and east throughout Eurasia.

A Scientific Controversy

Another problem for the Lajia find is the scientific controversy it has sparked. In 2010, Chinese team analysed the Lajia research, and attempted to re-create the “millet” noodles. They disputed the “millet only” noodles explanation, and argued that the Lajia noodles weren’t made only of millet. They pointed out that wheat had already arrived in this part of China as early as 2500 BC. Perhaps the noodles were made of a mixture of millet and wheat. Although an impressive picture was taken of the noodles when they were first unearthed, they later disintegrated. Our ghostly noodles have vanished, only whetting our appetite to find out more.

In 2014, the dissatisfied original scientists published their own comprehensive response. They re-analysed their finds, establishing that only millet was present (no wheat). They also conducted experiments, based on traditional methods, making millet only noodles.

Ancient Roman Diets: Where’s the Pasta?

One thing is clear. Unlike Lajia, no one has yet dug up a bowl of spaghetti in Pompeii (or anywhere else in ancient Italy). In fact, we know quite a lot about about what the people of Pompeii, and Romans more generally, were eating. Pasta just wasn’t on the menu and certainly it wasn’t the staple food it is in Italy today.

Archeologists have found all sorts of food remains in Pompeii: wheat, barley and millet of various kinds as carbonized grains. The people of Pompeii baked these grains into bread, but not, it would appear, into pasta. Pompeii was a substantial urban centre and Pompeiians ate a very diverse diet of locally produced and imported food (except pasta). There is no reason to think that the absence of pasta was unusual. The description below gives a good idea of what they (and other Romans) did eat:

The typical Roman meal of the lower classes consisted of bread (rich in bran and impurities), wine, vegetables—onions, garlic, and chick peas were typical of the lower classes … —lard, some fruit, and olives. In fact, Cato informs us that olives and bread were the basic foods of farmers and the working class … Vegetables were probably the most frequent accompaniment to bread but they could alternate with other poor dishes like fish and cheese. Meat was generally a luxury, but some types were available to the less well-to-do classes, like sausages, ham, or poultry, which could form part of the diet of urban populations … In the countryside, the consumption of meat was rarer and generally related to festive occasions. Puls—a porridge of cereals mixed with water, salt, and a little oil … —and dairy products were an alternative source of protein, …

Giovanna Belcastro and others, Continuity or Discontinuity of the Life-Style in Central Italy During the Roman Imperial Age – Early Middle Ages Transition: Diet, Health and Behaviour

Indeed Belcastro and her colleagues trace the evolution of diet in Italy in early Middle Ages. Their conclusion is that the same kind of diet continued, with a slight increase in the consumption of protein.

Lasagna and Lozenges

Thus the spread of pasta as part of the Italian diet occurs sometime later in history. Yet there are snippets of things that could “at a stretch”, be pasta. Whatever they are, we need to remember that they are the exception rather than the rule.

Some say ancient Etruscan frescoes are evidence of ancient pasta. Others disagree. However, whether they were or not, it is pretty clear that the Etruscan tradition did not survive. Roman total war eliminated their culture from the Italian peninsula.

Ancient Latin texts do however speak of “lagana”, something which over many centuries may have eventually evolved into lasagna (at least one kind of pasta). Silvano Serventi and Françoise Sabban book Pasta: the Story of a Universal Food notes that lagana, originally from the Greek “laganon”, was a thin sheet of dough. Lagana’s superficial similarity with lasagna is dispelled when we learn that the ancient Greeks flavoured it with lettuce juice and spices and deep fried it in oil. The later Greek Grammarian Hesychius defined it as: “a type of small cake, made from the finest wheat flour and fried in a frying pan in olive oil.”

In a 4th century cookbook it shows up in a more familiar form as layered pastry, alternated with meats, cooked in an oven. In contrast to modern lasagna, this lagana wasn’t boiled in the cooking process. The church fathers were using the same word to describe a dry flat bread used in religious ceremonies. In the 6th century, Isidore of Seville describes laganon as first boiled then fried in oil. Modern lasagna must wait many centuries more. Eight hundred years later, we find references to “lozenges” of pasta (about the size of a hand). These might be fried as a “fritters” or combined in cake like preparations. Indeed the word “lozenge” referred to the shape, rather than to a particular way of cooking. The fried version, in time developed a new name: “fritelle”.

A modern day Roman cookery book gives us Horace’s recipe for “Fried Pasta” with leeks and chick pea soup. Essentially, lagana was paper thin strips of dough fried in oil. The writer theorises that as Romans tended not to use cutlery, they instead used the fried pieces as edible scoops when eating soups. Some may say this is pasta. I am not convinced. A new version of Horace’s “chick pea” and “pasta” dish is now a traditional Salento favourite.

Noodles Make a Splash in China

Meanwhile, back in China, noodles are beginning to “make a splash”. Unlike the West where “durum” wheat was eventually to be the foundation of a wide variety of dry pastas, in China durum wheat did not exist. Instead softer wheat varieties that the Chinese cultivated were best suited to making fresh noodles cooked immediately. Already references to “bing” – a generic word that included both pasta like preparations and wheat bread were growing around 200 BC. By 300 AD the scholar Shu Xi writes his “Ode to Bing”.

His poem is a paean to a wide variety of “bing”. Each season has its own bing. Some of those he mentions evoke the many shapes of Italian pasta known today. “Dog’s tongues”, “piglet ears”, “dagger laces”, “cupping glasses”, “candles”, immediately bring to mind similar shapes found in Italian pasta. China was well ahead of Italy as we shall see. By the tenth century pasta like foods became known as “mian”, and China continued to develop its diverse expertise.

By the Tang dynasty (600-900) AD, pasta like preparations were a part of everyday life across China. With the Mongol mastery of both East and West from about the year 1179, Arabic treatises began to arrive in China, including treatises dealing with the making of various pastas. In China, “noodles” always remained a fresh dough tradition. The Chinese adapted it to produce noodles with a wide variety of other products, such as beans. Moreover their extraction of gluten from dough, enriched Chinese cuisine in other ways.

Tomb of Zhao Dajun

10th Century AD

By the Mongol (Yuan) dynasty the Chinese noodle tradition came in innumerable forms. Now called “mian” it included (adopting the terms in translation used by Serventi and Sabban) pasta slipped into water, red tagliatelle, fettucini, yam pasta, string pasta, hanging pasta, palmettes, turquoise vermicelli, chicken foot pasta, hand stretched pasta, hand rolled pasta, cut pasta, fine pasta and hook pasta. Here is an astonishing and early noodle tradition that Italy was to rival only centuries later. It is time to return to the Italian scene.

Pasta – Tria – Ittriya – Sicilian Threads

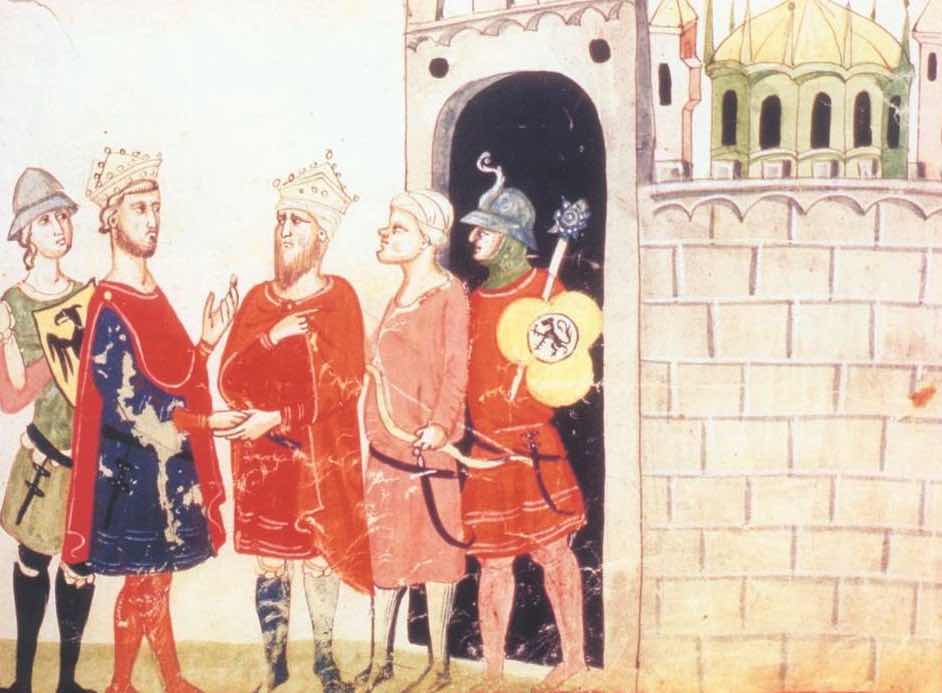

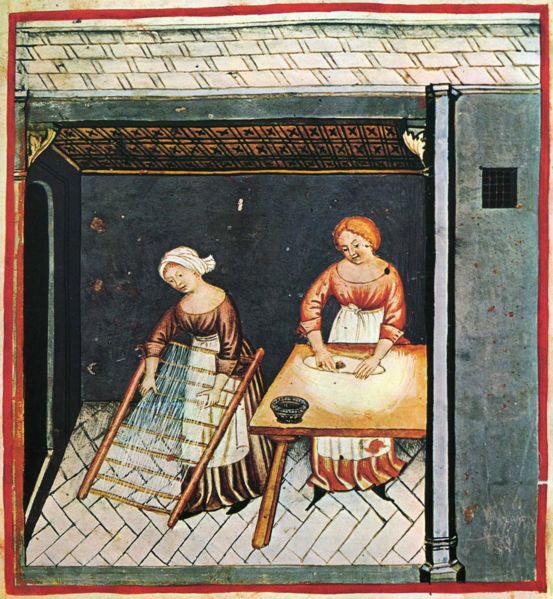

The image above from a medieval picture book on good health, the Tacuinum Sanitatis appears online in a variety of places, including in an article which confidently starts by telling us we need lose no more sleep. Pasta was “invented in Italy”.

Even though the writer with little thought will realise from his own caption that the illustration points to pasta being in the Middle East, not Italy, it is as if the connection is invisible.

As it turns out, we find three Latin versions of the Tacuinum Sanitatis in different European cities. Two versions refer to pasta as “tria”. As we shall see below this is similar to an Arabic word for pasta. Incidentally it is also the same word used by ancient Greeks and Romans much earlier – although for flat cake-like preparations. All three versions of the Tacuinium contain essentially the same discussion. The author observes that pasta is “very nourishing” and that it is “good for the young”, and that it should be prepared with “great care”. One version of the Tacuinium attributes, Abu’l Hasan (the original Arabic author) as the source, and in another (in an additional note) it cites no less a figure than the world famous Persian philosopher and scientist Avicenna (Ibn Sina)! Too soon to turn down the bed covers just yet.

If we discount lagana (which we have already discussed), the first recognisable references to something like spaghetti in Italy comes from Sicily during the Norman kingdom. Barilla pasta know this, and state as much in their history of pasta. They proclaim Palermo the capital of pasta:

Palermo è storicamente la prima, vera capitale della pasta perché le prime testimonianze storiche di produzione pasta secco al livello artigianale-industriale si riferiscono all’XI secolo in Sicilia, regione allora profondamente influenzata dalla cultura araba …

Palermo is historically the first, true capital of pasta because the first historical evidence of production of dry pasta at an artisan-industrial-scale occur in the eleventh century in Sicily, a region then profoundly influenced by Arab culture.

Barilla, La Pasta, storia, technologia, e segreti della tradizione italiana

(own translation into English)

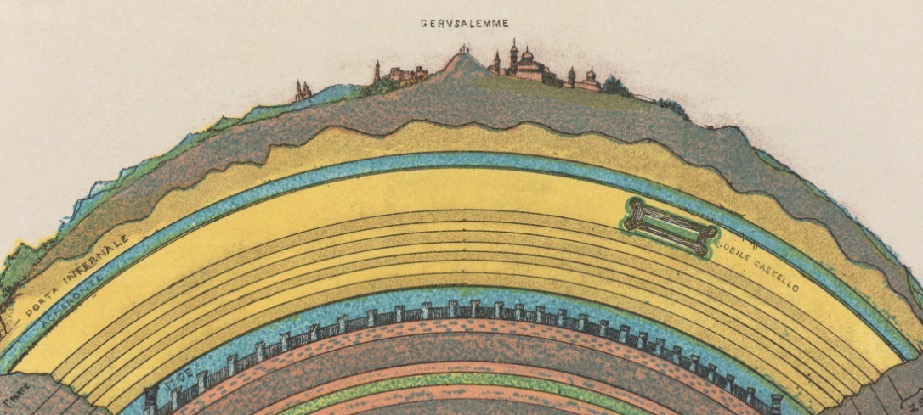

We have already met the geographer Al Idrisi in connection with his remarkable map making exploits, for the Italo-Norman King Roger II. Around 1154, Al Idrisi wrote in the “Book of Roger” (an Arabic text) that Trabia in Sicily was a major producer and exporter of a pasta product called in Arabic “itriya” (something very like to today’s hand-made dried spaghetti).

… si fabricca tanta pasta in forma di fili – chiamata triyan …che si esporta ne tutte parte, nella Calabria e in tanti paesi musulmani e cristiani anche via nave

Pasta, called itriya, is manufactured in the form of threads and is exported everywhere, to Calabria and in many Muslim and Christian countries, including by sea.

Al Idrisi, The Book of Roger, cited in Barilla, La Pasta, storia, technologia, e segreti della tradizione italiana

(own translation into English)

Apart from anything else, this brief extract shows that people were eating a spaghetti like pasta across the Mediterranean. Pasta crossed both the religious and geographical boundaries. More, Sicily was a major producer, as it is the only such site which Al Idrisi’s notes in comprehensive almanac of the known world. Even more significantly durum wheat (the essential ingredient of dry pasta) was introduced to Sicily during its Arab period.

Pasta Across the Mediterranean

From this point, the hunt for the origins of pasta takes us through Spanish (and Arab-Andalusian) culinary history where numerous culinary texts mention “fidaws” and itriyya as stringy dough. The medieval literature speaks of an established culture of using such pastas. It is a culture that is also connected with Algerian “rechta” – a word which links these western pastas with “rishta” – noodles in far off Persia.

Here is evidence as to how pasta as we know it, was absorbed into Italy. As we trace back the story, we find that in the ninth century the Arab writer Ibran Al Mirad, described various forms of pasta. In another source we read the following:

As early as the ninth century, the Syrian physician and lexicographer Ishu bar Ali referred to itriyya as dried strands of semolina dough that are boiled. One of the foremost medical authorities of the Middle Ages, Ishaq ibn Sulayman of Egypt, discoursed on the preparation of pasta in his 10th-century Kitab al-Aghdhiya wa’l-Adwiya (The Book of Foods and Cures, known in the West as The Book on Dietetics). Further east, the late-10th-century lexicographer al-Jawhari, who hailed from the Silk Road city of Otrar in southern Kazakhstan, defined itriyya as a food similar to hibriya, or “hairs” (possibly “flakes”) made from wheat. …

Tom Verde, Pasta’s Winding Way West

Indeed as early as a 5th century boiled pasta makes an appearance in Jewish religious law (as mentioned above), due to its exemption from tithing. The dry pasta (which Italians were later to make their own in innumerable new forms) comes from, or through, the Middle East. It wasn’t invented in Italy.

Interestingly, to the extent that pasta might have been “Middle Eastern” in the past, it is nowadays marginal in Middle Eastern cuisine. Food cultures continue to evolve everywhere, and rice has taken the role that pasta played, or might have played in the past, in that part of the world.

Pasta – An Italian Staple Food at Last

So when did pasta become an Italian staple? When we consider the answer to this question, any instinctive presumption for Italian invention evaporates. Even in the 1500s pasta, although known, was not a core part of the Italian diet, and was best known in Sicily.

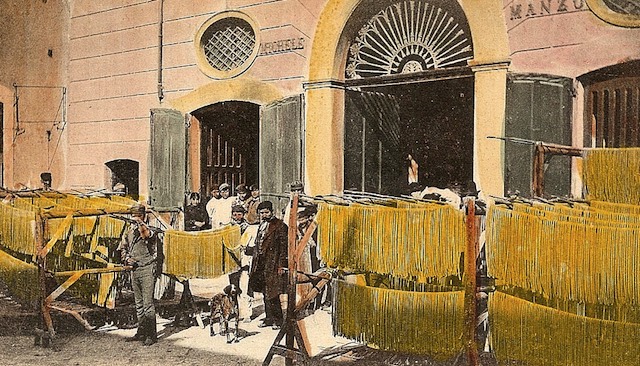

As Albert Capatti and Massimo Montanari recount in Italian Cuisine A Cultural History, it took centuries for pasta to become a staple. By the seventeenth century, the breakthrough came in Naples when new means of production lowered the cost, making pasta the food of the poor. So much so, that when visiting Naples in 1789 Goethe wrote that “macaroni of all kinds … are found everywhere at a low price.” Also at the end of the same century a Parisian could advise a friend, “Are you serving soup to an Italian? But Italians eat nothing but macaroni, macaroni, macaroni.” Not long after the tomato would be added. Italian cuisine as we know it has arrived.

These accounts present the big picture, but perhaps they are missing something. In the picture in the Tacuinium, women are making pasta in what appears to be a simple domestic process. This was something the illustrator saw, perhaps in Lombardy where the image may have been created. In Puglia (and many other parts of Italy) varieties of pasta such as orecchiette and fusili, the culinary art (primarily) of countless women, show the eminent practicability of producing pastas of all kinds without complicated machinery. Surely these types of pastas also have histories that the history books have not captured.

Jen Lin-Liu’s Noodle Road

What of Jen Lin-Liu’s journey? We left her at the beginning of her odyssey. Her journey is indeed remarkable. As she travels West, she concludes (as others have done) that noodles and wheat are intimately connected. Her journey takes her through Lanzhou, the home of “hand pulled” noodles: an originally Hui culinary art of impressive skill. She is no longer in the Han heartland, and in place after place she finds unique noodle dishes which the people of the region claim as their own.

The realization of the complexities of ethnicity in China grows as she becomes familiar with the country. Growing up in America she is simply “Chinese”, a minority in a majority “white” country (as America conceives itself). In China, people she meets see her as “Han” in contrast to the other ethnicities of the vast country. Suddenly she is part of the “majority”. It is a role with which she is unfamiliar and not entirely comfortable.

As she travels west she encounters more and more “noodle” dishes. In Tibet she finds “Momo” – a yak dumpling. The Uighur people further west use hand pulled noodles and a kind of tagliatelle, but locals tell her that they are Hui dishes from further east. Bread was the Uighur staple of choice. Here, however she first describes the meat dumplings called “manta”, a dish that appears in various forms from western China to Turkey.

In Kyrgyzstan, her host tells her that the cuisine is “basically meat and dough.” Shaped into squares and strips, the dough is added to a variety of meat dishes. Hand pulled noodles were still on the menu, even having now left China. In Uzbekistan she finds manpar, square noodle soup which further east in Tibet went by the name of mian pian. Here she also notices that the “manti” are made with egg, a practice linking to the egg noodles of Italy far to the west. Yet dominating the cuisine of much of this region is rice pilaf, known locally as “plov“.

Rice’s culinary triumph becomes even more evident as she explores Iran. It takes her some pages of describing the delicious primary foods of Iran: ghormeh sabzi (lamb stew with green herbs), fesenjoon (a chicken dish served with rice), khoresht kheme (a chick pea soup), kebabs and kubideh are among those she mentions. Iranians serve rice in a variety of ways including as bagholi polow (a pilaf with dill and fava beans). Tah-dig, a golden crust on the bottom of the rice dish is always the most prized. However even here the noodle is present in the form of ash-e-reshteh or ash-e-lakhshak. It is a noodle soup present in Persia back to the ninth century. She notes moreover that the word for “cook” – ashpez – references “ash” – the central Asian word for noodles. Though today noodles are not rated highly in this part of the world, or in Turkey, as she discovers.

With more adventures in Greece and Turkey (where she finds su borek – a Turkish lasagna), finally her journey takes her to Italy. Puglia to be precise, where she observes “I had no idea eating could be so exhausting”. It is an observation that brought a smile to my face, knowing exactly what she means. Her journey comes to an end as she explores Italian regional cuisines.

Her book is as much about life as it is about food. Here we have only traced a small subset of the stories her book recounts. Her encounters were not only with food, but with many men and women who helped her on her journey. It is an intimate account of her relationship with herself, her husband and the world around her. There are, after all, more important things than noodles. I recommend you to her book.

Ribbons of Dough Through Geography and Time

This article has grown longer than it aught, but its pursuit has taken us far afield, to places and thoughts we might not have otherwise discovered. If the words were not already so many, I would tell you of koshari, Egypt’s national dish which combines both pasta and rice, or the three traditional varieties of Syrian ma’ccarona, or Lebanese manti, and so many more dishes in which pasta features.

Tomato sauce and pasta, so defining of Italian culture in our era, are debts Italy owes to the world. For if the land we today call Italy had been an island to itself, Italian cuisine would never have come to be. Italy has repaid the debt in the unique and notable contribution of Italy’s cuisine to the world’s food cultures.

The word pasta (dough) is Italian, but the food … that is truly global. We can say the same for China’s noodles and the global cuisine to which it has contributed. Undoubtedly food cultures will continue to evolve everywhere, and be the better for it, as they continue borrow from each other.

Selected Sources

Jen Len-Liu, On the Noodle Road: From Beijing to Rome with love … a true story, Allen & Unwin, 2013

John Roach, 4,000-Year-Old Noodles Found in China, National Geographic

Wei Ge, Li Liu, Xingcan Chen and Zhengyao Jin, Can Noodles be made from Millet? An Experimental Investigation of Noodle Manufacture Together with Starch Grain Investigation Archaeometry, 53:1, pp 194-204 (2010)

Houyuan Lu, Yumei Li, Jianping Zhang, Xiaoyan Yang, Maolin Ye, Quan Li, Can Wang, Naiqin Wu, Component and simulation of the 4,000-year-old noodles excavated from the archaeological site of Lajia in Qinghai, China

Erica Rowan, Elisa Rastelli, Valentina Marriotti, Chiara Consiglio, Fiorenzo Facchini, and Benedetta Bonfiglioli, American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 132: 381-394, (2007)

Erica Rowan,Sewers, Archaeobotany, and Diet at Pompeii and Herculaneum, in ed. Miko Flohr and Andrew Wilson, The Economy of Pompeii, Oxford University Press, 2017

Giovanna Belcastro and others, Continuity or Discontinuity of the Life-Style in Central Italy During the Roman Imperial Age – Early Middle Ages Transition: Diet, Health and Behaviour

Melitta Weiss Adamson, Regional Cuisines of Medieval Europe: A Book of Essays, Routledge New York,2002

Silvano Serventi and Françoise Sabban, translated, Anthony Shugaar, Pasta: the Story of a Universal Food, Columbia University Press, 2000

Silvano Serventi and Françoise Sabban, translated, Anthony Shugaar, Pasta: the Story of a Universal Food, Columbia University Press, 2000

Mark Grant, Roman Cookery: Ancient Recipes for Modern Kitchens, Serif London, 1999, 2015

Vincent Scordo, The History of Pasta Shapes – The Italian People and Pasta

Tom Verde, Pasta’s Winding Way West

Barilla Pasta, La Pasta, storia, tecnologia e segreti della tradizione italiana

Alberto Capatti and Massimo Montanari, Italian Cuisine A Cultural History, (translation by Aine O’Healy), Columbia University Press, 2003

Note

Updated 20 December 2020. An earlier version of this article referred to a now deleted page of the International Pasta Assocation in the following terms. “The International Pasta Association still can’t bring itself around to this simple admission.” At the time the page began as follows:

“Many are the theories that have been presented concerning the origin of the pasta product. Some researchers place its discovery in the XIII Century by Marco Polo, who introduced the pasta in Italy upon returning from one of his trips to China in 1271. On chapter CLXXI from the “Books of the World’s Wonders”, Marco Polo makes a reference to the pasta in China. In our opinion, the pasta dates much further back, back to ancient Etruscan civilizations, which made pasta by grinding several cereals and grains and then mixed them with water, a blend that was later on cooked producing tasty and nutritious food product.”

Further investigation would however have found the following on another page of the site.

“The city of Dubai will host World Pasta Day 2018. The choice of Dubai is a tribute to the contribution that Arab culture has made to the invention of the most famous pasta format. In the 9th-century the Arabs brought to Sicily the Ittriyya, thin strands of dried pasta, later perfected by the Italian “Vermicellari,” that would become modern-day spaghetti. Pasta is extremely popular in Dubai, a global city where 88 percent of its residents are of foreign origin. Dubai, home to EXPO 2020, is a gateway to the Middle Eastern and Asian markets.” (24.10.2018)