Ancient Italy: The Arrival of Agriculture and the People from the Sea: 6000BC

In ancient times the mountainous spurs of the Apennines ran down Italy’s spine and the Alps were piled at its northern end much as today. But if we had been present in the ancient neolithic we would have seen an Italy which was unlike anything we know today. The coastline would have been somewhat different, although that would not have been the most dramatic difference. Italy was blanketed with forests and this part of the world was wetter than it is today.

It is 6000 BC; an era in which people from the sea arrived and brought with them agriculture. Millennia later Vesuvius would erupt. But the arrival of agriculture happened on the other side of Italy, near the rugged Gargano of Apulia, an oval serrated highland set between the Adriatic Sea and the plains of the Tavoliere to the west.

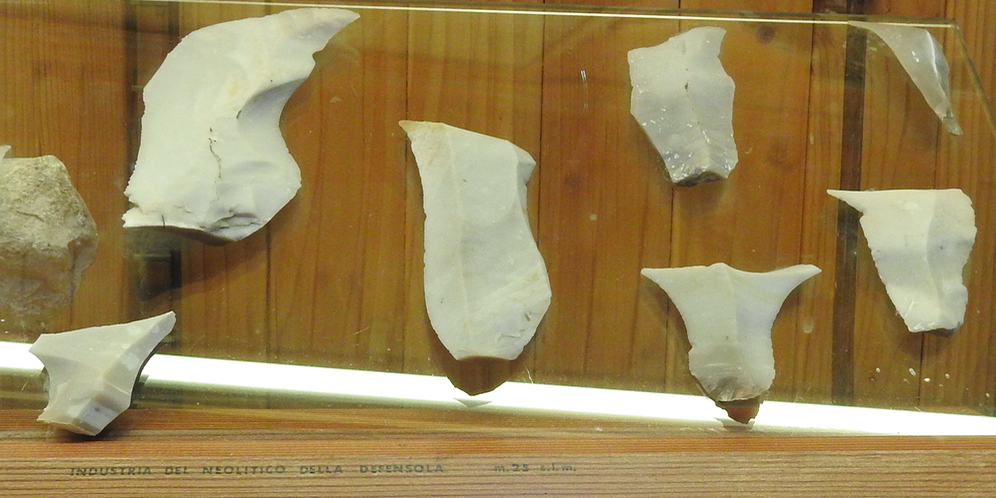

Italy was not empty of people when these new arrivals came, but its people were scattered hunter-gatherers, few in number. Like the new arrivals they were stone age people. All their tools were laboriously hand crafted of stone, wood, bone, thong and fibre. Many remnants of their stone tools can be found displayed in visitor centres in the national park that now covers much of the Gargano.

The new arrivals who came to the vicinity of Gargano in this ancient time, however also brought entirely new technology. Though it seems humble and unremarkable to us now, it was revolutionary in its day. While they still used the older techniques; still hunted, still gathered when occasion demanded, such practices now supplementary to their main way of life: animal husbandry and agriculture. They had domesticated goats and sheep and they had learnt the cultivation of grains such as emmer wheat and barley. They were the first farmers in this part of the world.

The manner of their arrival would seem unremarkable to us today also, although again it represented a revolution. They came across the Adriatic on small boats, bringing their livestock and grains with them. Perhaps their journey involved island hopping across the Adriatic driven with nothing more than oars. Perhaps the sail had already been invented, given the distances that were sometimes involved, in the known sea voyages that were made in the Mediterranean at this time.

The movement of which they were a part had started two thousand years earlier and it was vast. It is a subset of the stories of human interconnection revealed by archaeology and by the data hidden in our genes and the genes of plants and animals that humans carried with them.

Although it was not the only place this happened, agriculture was invented in the Fertile crescent of the Middle East. Once started it spread: to the west through the Mediterranean and Europe; and to the east across Iran and then into India. It was a spreading wave, not just of ideas, but of people, as each generation set out to found new villages in land that had not already been cultivated. It would take 2000 years for the movement to reach Italy and it would continue on into Europe for thousands of years more. Ultimately it would reach Europe’s most northerly climates.

What would the first arrivals in Italy have seen? As they crossed the sea the mountains of the Gargano would have risen before them to a great height; an excellent place to seek understanding of this world. If they had climbed its slopes and looked down on the plain the new arrivals would have found a land covered in forests; as much of the northern Mediterranean shore was at this time. Pine forests dominated the slopes of the mountains and hills that cover much of Italy. While on the plains mixed oak woods dominated. Almost nothing of these ancient woodlands now survives in Italy.

Various genetic studies of human populations as well as the genetic origins of the plants and animals used in Neolithic Europe and archaeological finds have established the outlines of this story beyond doubt. Recent genetic studies point to a common genetic connection that stretches across the islands of Crete and the Aegean to southern Italy and Sicily stronger than to mainland Greece; an echo of these ancient sea migrations.

The hunter-gathering people who were already here did not disappear. Over time the communities intermingled and both farmer and hunter gatherer ancestors remained among the ancestors of the people of southern Italy, as elsewhere in Europe.

Conflict with the existing population is likely to have occurred, given human history, but the continued signature of hunter gatherer DNA of the original people of Europe in modern European populations tells us that the story was more complex than one of simple displacement and extermination. To differing degrees, the two populations became one over time.

These settlers were farmers; and the places they chose to first settle were also influenced by the soils most suitable to their farming; although they often sited their settlements in transitional zones where both farming and the older practises of hunting and gathering could be carried out in complementarity with each other. These places were often terraces close to the lowland areas best suited to the farming they practised. The Tavoliere, the plain just to the west of the Gargano, is recognised as one of most densely populated parts of neolithic Italy from which the farmers spread out to the rest of Italy.

Although initially their settlements were open, soon enough it became apparent that they needed to defend themselves from their neighbours (in contrast to the Bronze Age villagers of Campania). This is seen in the large ditches and mounds they built to surround around their larger settlements which could house up to 250 people; although unfortified smaller settlements were also common in this period. In some areas the villages were surrounded by ditch and fences; in other areas stone walls were constructed — according to the available materials.

Their herds were mainly sheep and goats, though also including a small number of cattle and pigs. These domesticated animals were a source of meat and likely also of milk. They supplemented their animal husbandry with some hunting of the deer and wild boar that were common in this era. They grew a variety of crops – particularly varieties of wheat and barley. As with animal husbandry, domesticated crops were supplemented with gathering wild produce such as berries and the wild olives that grew in the countryside.

Of course, we have no portraits of what these early farmers looked like. However, the science of genetics tells us that their skin was light and their eyes tended to be brown. This contrasted with the existing inhabitants whose complexion was dark and who had blue eyes.

Although many people of Europe (particularly along the Mediterranean) still carry the genetic patterns of these ancient farmers; genetically the people of Sardinia are closest to them and so these ancient farmers might have looked something like Sardinians. In other words, they likely looked much like people who live around much of the shores of the Mediterranean today.

Images

- View of the Gargano, looking north east across Lago Varano

- Neolithic tools from collection displayed at Visitor Centre in Foresta Umbria, Gargano National Park

- View of Foresta Umbria

- Extract from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Macomer_-Costume_tradizionale(01).JPG by Gianni Careddu [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

Sources

Ron Pinhasi et al, “Tracing the Origin and Spread of Agriculture in Europe”, PLOS Biology December 2005 Vol 3, No 12, pp 2220-2228

Caroline Malone, “The Italian Neolithic: A Synthesis of Research”, Journal of World Prehistory, Vol. 17, No. 3 (September 2003), Springer, pp. 235-312

Andrew D. Isaac, et al, “Genetic analysis of wheat landraces enables the location of the first agricultural sites in Italy to be identified” Journal of Archeological Sciences, 37 (2010) 950-956

Peristera Paschou et al, “Maritime route of colonization of Europe”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), 2014, Vol 111, No 25, pp 9211-9216

Zuzana Hofmanová et al, “Early farmers from across Europe directly descended from Neolithic Aegeans”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), Vol 113 No 25 2016 pp 6886-6891

Farnaz Broushaki, Early Neolithic genomes from the eastern Fertile Crescent, 10.1126/science.aaf7943 2016

Frederico di Rita, Donatelli Magri, An Overview of the Holocene Vegetation history of the central Mediterranean coasts, Journal of Mediterranean Earth Sciences, 4 (2012), 35-52

Roland Noti et al., Mid- and late-Holocene vegetation and fire history at Biviere di Gela, a coastal lake in southern Sicily, Italy, Veget Hist Archaeobot (2009) 18:371–387

2 Comments

Michael Curtotti

Thanks Marco!

Marco Kappenberger

Thank you !