Of Villages and Vesuvius: 1800BC

The ancient mount Vesuvius rises high above the Campanian plain. The plain – a great oval ringed by mountains – stretches north, east and south for hundreds of kilometres. Along its northern edge, the river Volturno, the longest river in Italy, flows to the sea. Below Vesuvius is a great bay: the Bay of Naples, although it will be well more than a thousand years before new arrivals from the Greek island of Euboea build a city here which will bear that name. We are Italy’s deep past, although the very idea of Italy is yet to be invented.

Vesuvius is not the only volcano here. It is part of a complex that has erupted many times. The huge Roccamonfina rises on the north of the plain. Campi Flegrei (a complex of archaic super volcanoes) lies on the coast to the west of Mt Vesuvius. The volcanic islands of Ischia and Procida rise out of the sea just offshore. As for Vesuvius itself, it has been restless for many months now, but the people who live nearby are unaware that anything worse is ahead.

From the ancient Campanian shore ancient village-to-village tracks criss-cross the region. We will follow a path that will take us around the northern skirts of the mountain. As we journey, we see well tended fields – full of the still green wheat and barley. It is springtime.

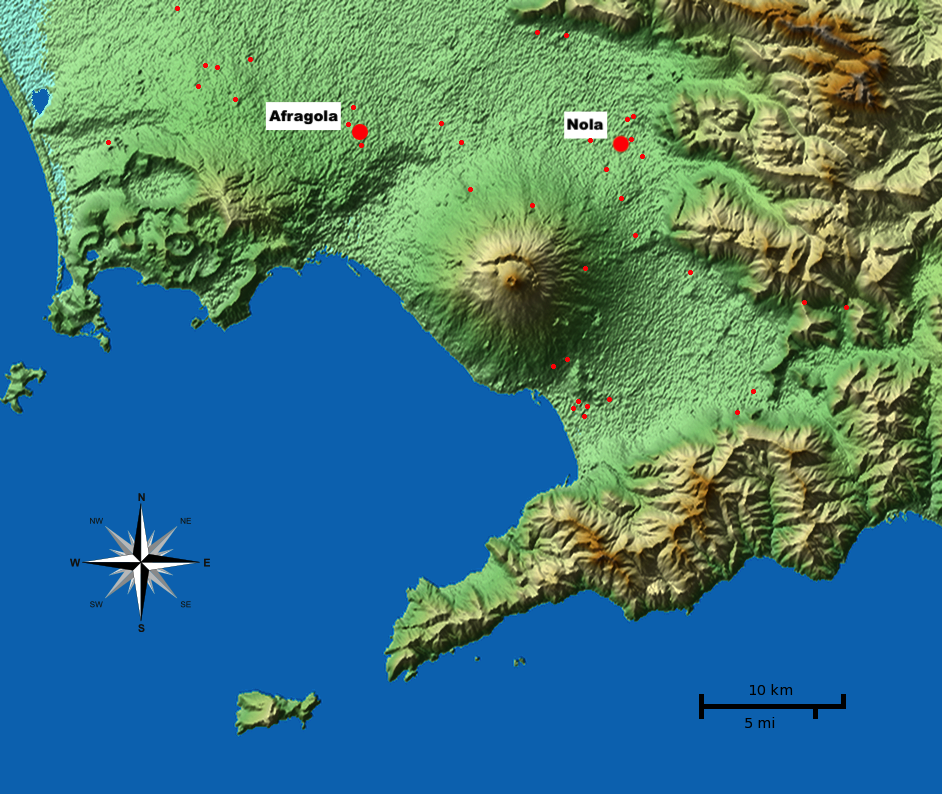

Our goal is the village of Nola. It is only one of many. Over a hundred are scattered across the plain that surrounds the mountain. For this land is already well inhabited and its volcanic soils are rich. The people who live here are farmers and herders. They also hunt the wild boar and deer that are found in the many forested areas that are part of the landscape.

We will walk much of the day leaving behind us the wooded slopes of Mt Vesuvius as we pass it to the north. After walking some 20 kilometres we pass through a dense grove of ancient oaks. As we emerge we see ahead of us the outlines of the village. Fig and olive trees (the latter probably wild) are found in the vicinity of the village, as are almond trees. Beyond the village we see a forest of beech trees. Throughout, is a green landscape full of young cereals. The first we can make out of the village itself are the tops of thatched triangular roofs of buildings. Herders are tending sheep or cattle in fields near the village. As we come closer we see the wicker fences that mark the edges of the village. These are not defensive structures however. In front of them we see a villager drawing water from a well. Not far from where she stands, an open area is evidently a threshing floor – although it is not harvest season. As we cross the wicker fence into the village we pass a pen full of goats. Most of them are pregnant. Others are tied outside – feeding on leaves and shrubs brought for them by their owners. Behind is a kind of long house. It is almost 5 metres tall and 15 metres long. It’s roof, which is very steep, reaches almost to the ground – and the walls underneath it continue its angle to the ground. The end of the long building which faces away from us is rounded, while the home’s door opens on a flat wall on the side facing us.

People are going about their affairs. Children are playing outside. An adult emerges from the building. She is dressed in handmade fabrics woven from local plants. She is a young adult. As she emerges her three children approach her, demanding something of her, but she sends them away. She is busy. Behind her an older man emerges. He might be her father. They are both carrying wicker baskets. They are going out to collect mushrooms and pass you by as they head out into the fields on their mission.

There are a number of buildings, but you enter the largest. Inside the building is divided into three sections. The first is an open area. Here people are engaged in conversation and communal work. The adults vary in height. The shortest are about 4 and a half feet tall – the tallest approach six feet. A horizontal stone disc is being spun around by one of the adults while wheat is poured into the central hole of the axis by a youth. Flour emerges from a channel carved into a plate under the grinding stone. Wicker baskets and pots line the walls.

Further inside, in the second area, are the living quarters. Here a communal meal is being shared. The mealtime conversation is in a language that we do not recognise. It may be an ancestor of the ancient Italic languages that would be spoken here a thousand years later. It may be another language – we are not sure. They squat in a circle – each has a bowl which can be rested on a pottery stand. Nearby there is an oven and a rich aroma emerges from the ceramic pot hung over it.

The final room of the building is a storage area. There are pots of many kinds. Some contain dried figs. Some contain almonds. Wheat and flour is stored in others. Dried berries and acorns in others. The pots are of a variety of shapes and sizes. Some are marked with linear designs – zig zags and triangles. Some are decorated with white shading. Larger vessels are dug into the earth and filled with wheat. Cured portions from animal carcasses hang along one side of the building.

In another part of the village we find furnaces for the smelting of copper.

Although we cannot see them, outside the main building small pottery vessels have been buried. Inside are placed 6 month old fetus’: pre-term children who did not survive birth. They are interred close to the family home. A larger interment is further away where other dead of the village are placed in a communal cemetery.

The village of Nola is part of a culture that is spread across this area and much of the Italian peninsula.

Closer to the sea – directly to the west of Nola lies the village of Afragola. It lies near an ancient river that flows a kilometre from it. It is surrounded by oak woodlands. The village has 24 buildings. Six of these are homes. Like the buildings we have seen in Nola, they have the same basic shape: horseshoes – which have a flat face at the south-west oriented entrance – with the oval side of the building oriented to the north-east. Although these buildings are smaller than the large ‘long house’ found in Nola. The same high pitched thatched roofing has been used. The other buildings have practical uses. They are arranged as out-buildings for the main residential building. One is used for the store room holding wicker baskets full of wheat. The building also contains pottery measuring cups and vessels of various sizes. Another building is used to store wood. The villages is divided into plots by straight and curved wickerwork fencing. As in Nola there are no defensive structures.

The people of this time and place, whatever they may have feared, they did not fear attack from their neighbours.

When the volcano exploded – it caught them by surprise. Like the eruption that happened near 2000 years later and which buried Pompeii, the villagers would first have seen a sudden and dramatic explosion. Dark clouds of super heated ash and pumice would have risen far into the sky. To add to its terrifying aspect, the dark clouds would have been punctuated by lightning generated by the electrical storm accompanying the cloud.

Soon the column would shoot up kilometres into the sky. Shortly after pumice would have begun raining down from the sky. Although each pumice stone was light, the thousands raining down like a thunder storm would quickly kill anyone caught out in the open.

Such was the fate of the young woman and her older father who had ventured out to gather mushrooms. Pumice rained down on them. They might have tried to seek shelter under a tree. But it was of no help. Suffocating gases and ash disoriented and separated them. Then they collapsed, their hands desperately trying to shield their lungs from air that had become deadly. Four thousand years later their remains would be discovered where they had fallen.

Back in the village of Nola the community would have first taken shelter in the buildings. As the pumice continued to rain down the roofs began to collapse. Their high angle however helped and no one was killed. A break came in the downfall. As they emerged from their ruined homes, the community would have seen a poisoned landscape covered with grey ash as thick as a deep snowfall. There would be no survival here. The people gathered their most important belongings and planned their escape. Whether they survived is not known, although their footprints as they fled were found imprinted in the ash. The goats tied in the pen did not survive. Neither did a dog which in its fear hid in one of the long houses.

At the same time that the volcano destroyed this village, it preserved its story. We do know this was not the end of the culture of these communities. Within a generation people would return here . New farms and settlements arose and continued the ancient way of life as if the volcano had never erupted. The names we have used for the villages are the names they have in our own time. Afragola is now a suburb in the city of Naples. Nola is a small town not far from its outer edge of urban development. The building of a supermarket and a freeway brought these Bronze Age villages to light.

Even this ancient story is not near the beginning of agriculture in this part of the world. It is an even older story, and it is connected with the arrival of a people who came from the sea and brought a way of life that had started far to the east.

Notes

The story as told above is based on archeological finds from the area from what is called the “Avellino Eruption” which occurred about 1800 BC. Below are some references to sources which describe the eruption and the archeology of the Nola and Afragola sites.

Giuseppe Mastrolorenzo, Pierpaolo Petrone, Lucia Pappalardo, and Michael F. Sheridan, The Avellino 3780-yr-B.P. catastrophe as a worst-case scenario for a future eruption at Vesuvius, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, March 2006, Vol 103, No. 12,

Claude Albore Livadie, A First Pompeii: the early Bronze Age village of Nola-Croce del Papa (Palma Campania phase), Antiquity, Dec 2002 76:294

Erik van Rossenberg, The discovery of an Early Bronze Age village at Nola (Campania, Italy). The Pompeii premise put to the test, PROFIEL, ARCHEOLOGISCH STUDENTEN TIJDSCHRIFT 11/2-3

Gabriele Rosato, Storie Sepolte: Il Villagio Del Bronzo Antico di Nola,

Images:

Southern Campanian plain. By Morn the Gorncompass rose from Maps_template-fr.svg: Eric Gaba (Sting – fr:Sting) – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9918806. Edited to add sites of ancient villages.

“In Old Bronze Age (3800 BP) village of Nola, the mold of one of a group of huts found partially buried, its interior, including pottery, perfectly preserved.” By Giuseppe Mastrolorenzo, Pierpaolo Petrone, Lucia Pappalardo, and Michael F. Sheridan [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

“A human victim of the Avellino eruption (ca. 3800 BP) found buried in a self protecting position typical of death due to suffocation.” By Giuseppe Mastrolorenzo, Pierpaolo Petrone, Lucia Pappalardo, and Michael F. Sheridan [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons