Women’s Work

Few of the millions who visit Pompeii every year would imagine that thousands of women laboured to clear the ancient streets on which they walk. Like other elements of Italian culture, ideas about “women’s work” have changed over time. The phrase of course brings to mind times when society pressured women to remain in the domestic sphere of the home. Yet even in the past, women could be found working outside the home as much as within it. The painting above by Filippo Palizzi shows women at work during the excavation of Pompeii. Palizzi was not the only painter to capture this theme. Below we see Eduard Sain’s painting of the same topic.

It is of course part of a broader pattern of the invisibility of women’s stories, as well as the purposeful exclusion of women from aspects of public life in most of history and in most cultures.

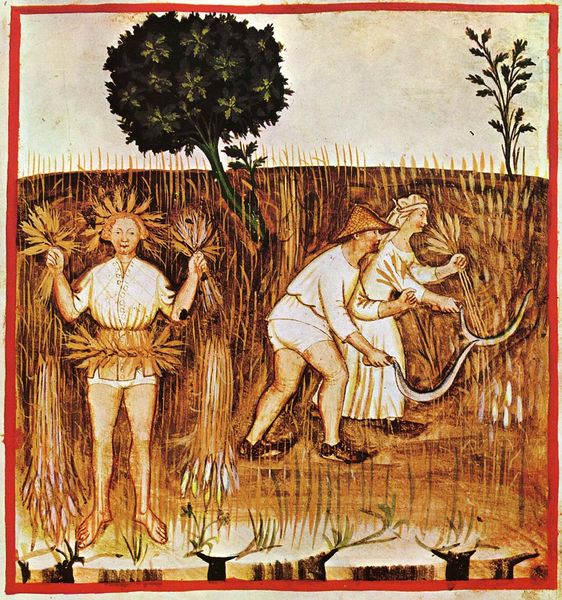

Women’s Work Among the Poor

As we explore this topic we find that we are as likely to encounter a “contadina” as often as a “contadino” in the historical record.

The American traveller John Headley, in his 1842 Letters From Italy, describes a variety of “women’s work”. He remarks that unlike his own country where field work: “is chiefly confined to men (except in the slave districts), [it] is here also performed by women.” He portrays a complex image of joyfulness and dignity coupled with the exploitative economic difficulties of life, particularly as they affected women.

“The peculiar costumes of the peasantry often gives them a very picturesque appearance in the fields. I have seen in the wheat fields near Naples twelve or fifteen women in a group, each with a napkin folded on the top of her head, to protect it from the sun — while the dark spencer and red skirt open in front and pinned back so as to disclose a blue petticoat beneath — contrasted beautifully with the bright green field that spread away on every side.

“They usually go to their work in the morning with their distaffs in their hands, spinning as they walk. … In the country between Naples and Rome, some parts of which are very beautiful, the wages of a woman in the field is a Carline, or eight cents per day, and she finds herself. One can hardly conceive how eight cents would buy her daily food, much less clothe and shelter her, but it is incredible on what a small sum an Italian will live. …

“… go back into the mountains and the extreme politeness and civility you meet at every turn endear them to you before you are aware of it. Male and female salute you as you pass, and in such a pleasant manner that you scarcely regard yourself as a foreigner.

“Visiting the silver mines on the borders of Lucca and Carrara, … the pleasure I received was soon forgotten in the sad spectacle that met me as I approached the mines. I never saw paler and more woe-begone faces than those of the females I found myself among. They were mostly young women, but poor, with sunken eyes, and colorless cheeks, and a perfect marble expression of features. They are employed in various departments, but chiefly in washing silver dust. Whether it be the cold mountain water in which their arms are constantly bathed, or the influence of the metal they separate, or both, I know not — but our hard-driven factory girls look like rose-buds, compared to them. …

“The next day we went into the mountains to visit the Seravezza quarry, and also the Mercury mines …, I entirely lost track of my companions. … while I stood midway on the mountain doubtful what course to take, a young woman about eighteen years of age overtook me. She was decidedly pretty, with a slight and graceful form. The everlasting distaff was in her hand, and she spun away as she slowly ascended the zigzag path. I inquired the road to the quarries, she told me she was on her way there and would accompany me. … I asked her if she was carrying the dinner to her friends in the quarries. ” Oh no,” she replied. Ah, said, I, in true Yankee inquisitiveness, I suppose you are going up to visit your husband? She burst into a clear laugh and replied, ” Oh, no, I am not married.” Well, then, said I in perfect wonder, what are you climbing this tremendous hill for? ” Oh, I carry quadrette,” she answered. ” Quadrette!” I exclaimed, what’s that?

“On inquiry I found that she was employed all day in bringing square blocks of marble dressed for pavements from the quarry to the plain. A thick napkin was folded on the top of her head, on which she placed the ” quadrette,” square pieces of marble, and descended with them to the manufactory below. It was a mile from the bottom to the top, and she spun as she ascended the mountain, and then returned with her “quadrette.” A mile up and a mile back, made each trip two miles long. She made seven a day, and received for each only a cent and a half. Thus she travelled fourteen miles a day, and carried seven miles, a heavy stone, and received for it ten cents. I looked at her with astonishment. Her features and form were delicate, and her voice and manner and all were so gentle and sweet, that I could not conceive for a moment that such a life of drudgery was her lot. Yet she seemed cheerful and happy. The wages of the men were about twenty cents per day.

John Tyler Headley, Headley’s Letters from Italy, pp 211-214

In Black Bread, the nineteenth century Sicilian writer Giovanni Verga presents a quite different picture, stripping his characters of all humanity, reducing “Red Head” a young mother who is breastfeeding her child on the way to the fields to “a real beast of burden … hoeing, mowing, sowing, better than a man, when she pulled up her skirts.”

Women’s Work in Literature: Trotula, Isotta Nogarola and Laura Terracina

These images of the life that was the common lot of the vast majority of women, is not however the full story as far as “women’s work” is concerned.

We have seen the fame of the writings attributed to the medical doctor Trotula of Salerno. Obstetrix (or midwifery), “ostetricia” in Italian, was long an almost an exclusively female profession. Women also dominated other professions such as “sarta” (tailor) and “tessitora” (weaver), “filatora” (spinner) and as the twentieth century approached teacher and nurse.

Italy has also had women who excelled (even in the Middle Ages) in fields such as science or literature, though of course far less well known than their male counterparts and often undertaking their work against societal and male opposition.

Isotta Nogarola (1418-1466) of Verona is such a case. A humanist and feminist she argued in one of her most well known works against the doctrine that Eve was primarily (if not solely) responsible for the “fall of man”. She wrote her argument in the form of a debate with Ludovico Foscarini. In the context of the time Isotta used male belief in the inferiority of women to argue for the greater responsibility of Adam. Her task is a difficult one. She uses Foscarini’s words towards the conclusion of the debate. “The first mother set torch to a great fire which, to our ruin, has not yet been extinguished.” Against such misogyny little could be done.

Hostility from the male humanists led her to withdraw into a life of religious seclusion on her family estate. Her writings from that time turned to religious themes.

Laura Terracina (1519 – 1577) of Naples was more fortunate in her career and became the most published Italian poet (male or female) of her century. Her greatest work was her response to Orlando Furioso. In it (among other things) she calls for women to leave behind the needle and thread and take up literature in defence of their sex. In her work she castigates violence and mistreatment of women and other social ills of her time. The video below demonstrates the continuing relevance of her work. It presents a reading of extracts from her work and is set to music.

Women’s work in Italian history and culture is of course a much larger topic than the brief dimensions explored here. It includes the work of many eminent women throughout history and in our own time. It includes the role of family, the economic and cultural systems in which it was embedded, and the political movements of the twentieth century.

Images

From Filippo Palizzi (1818-1899) – “Fanciulla pensierosa agli scavi di Pompeii” (1870) (Thoughtful Woman at the Excavation of Pompeii). For a discussion see Art in Pills: Pompei attraverso lo sguardo di Palizzi

Éduoard Sain, Excavations at Pompeii, (1865).

Video: Chi Nemico è di Donna” – Rime contro la violenza – Enna, 8 Marzo 2013 extracts from verses of Laura Terracina

Veggio il mondo fallir, veggiolo stolto,

e veggio la virtute in abandono,

e che le Muse a vil tenute sono,

tal che l’ingegno mio quasi è sepolto.

Veggio in odio ed invidia tutto volto

Il pensier degli amici, e in falso tono

Veggio tradito dal malvagio il buono,

E tutto a nostri danni il ciel rivolto.

Nessun alben comun tien fermo segno,

Anzi al suo proprio ognun discorre seco,

Mentre ha di vari alletti il petto pregno.

Io veggio, e nel veder tengo odio meco;

Talche vorrei vedere per disdegno

O me senz' occhi, o tutto il mondo cieco.

***

Ben vi percuote il cor d'invidia il telo,

Che tenete le donne si vilmente.

A la femina il maschio non fa guerra

Tutti gli altri animali in terra.

O nimico del cielo, e di natura,

Come hai baldanza tu di por la mano

Sopra di bella & giovenil figura?

Onde ti vien questo tuo ardir si strano?

Ti fè de la tua costa il buon fattore

Uscir la donna con si bel disegno,

Acciò, che d'una fede, e d'uno amore

Voi foste uniti in questo regno!

Ben ti poi annoverar, con darti vanto

Tra crudeli Leoni, e maligni Orsi,

Quantunque di natura sia mordace

A la femina il maschio non la face.

Ne sarai forse primo, ne secondo,

Darai a tuo malgrado quel che dei:

Deh vivi tu con la tua donna in pace:

La Leonessa appresso il Leon giace.

Sources

John Tyler Headley, Headley’s Letters from Italy, Baker and Scribner, New York, 1848

Black Bread in Giovanni Verga, Little Novels of Sicily, translated by D.H. Lawrence, 1883

Rinaldina Russell (ed), Italian Women Writers – A Bio-Bibliographical Sourcebook, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut (1994)

Rinaldina Russell (ed), The Feminist Encyclopedia of Italian Literature, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, 1997

Virginia Cox, Women’s Writing in Italy (1400-1650), John Hopkins University Press, 2008