Caruso: Dalla’s Song of Love, Pain and Death

The song Caruso has genius in its verses, and it is one of the most popular songs Italy has given the world. The verses of Caruso came to singer songwriter Lucio Dalla in a burst of inspiration. “Ti voglio bene assai”: I love you very much. Such words (in any language) are among the most meaningful human beings share with each other.They are words which, with “Tanto tanto bene sai” – So much, so much, you know, resonate in the chorus of the song.

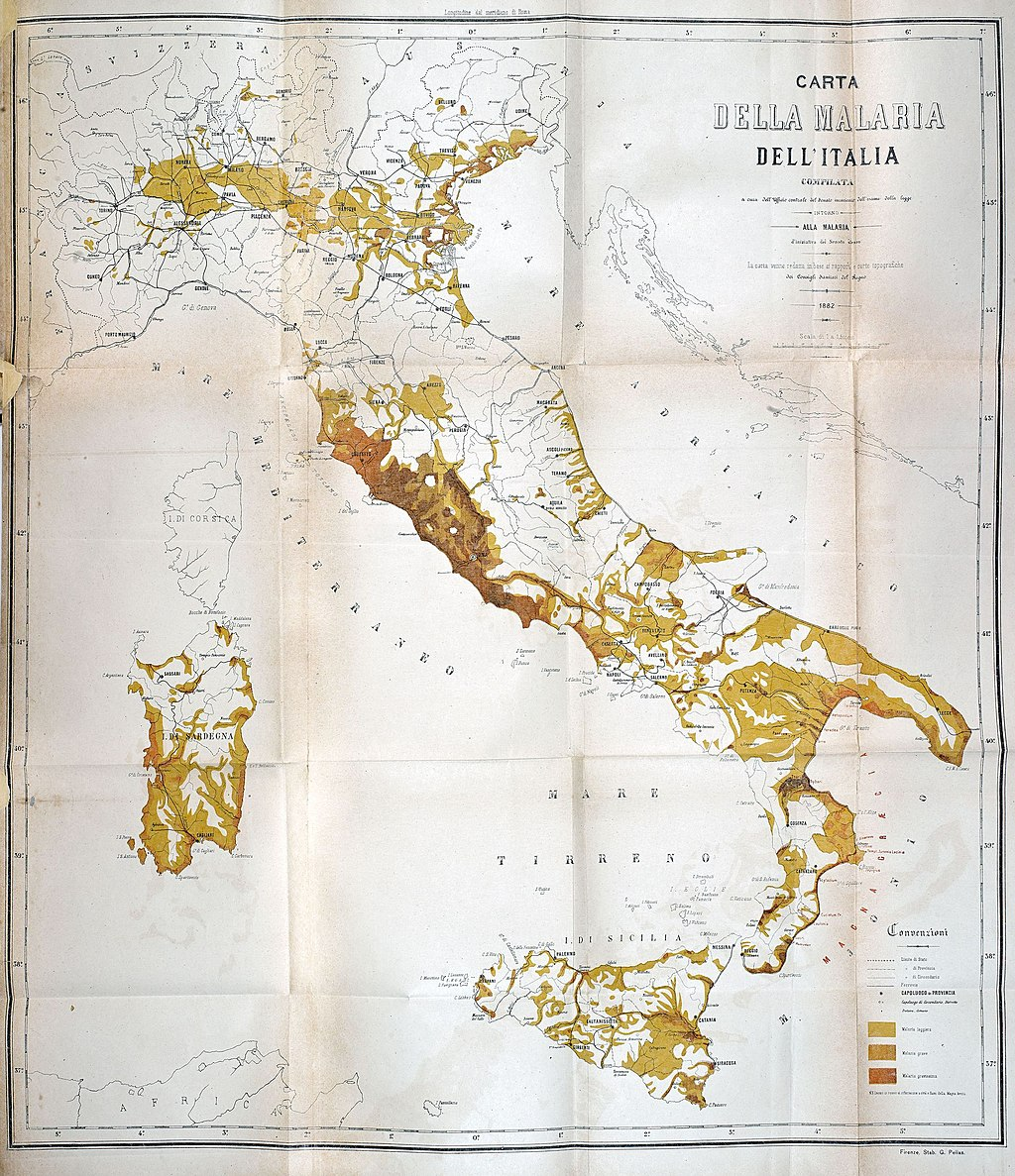

Yet these words are not where the song begins. Rather we are on a Terrazza, overlooking the “Golfo di Sorriento“. It is one of Italy’s most iconic and beautiful locations. The chorus too is evocative of this geography and the Neapolitan dialect. For Dalla, born in Bologna, Naples and Neapolitan music are objects of admiration. In part, the song gives expression to that admiration.

Accident and Inspiration

When Dalla was visiting Sorrento, accident and inspiration met. Dalla had not intended to stay at Sorrento’s Excelsior Hotel. But a faulty boat engine compelled his stay. Decades before, the great opera tenor Enrico Caruso had spent some of his last days at the hotel. While there, Dalla heard the local legends of Caruso’s stay: of his final inspired song heard far out to sea, and of his young lover. Caruso knows he is dying. His “lover”, although usually unnamed in the semi-legendary accounts still told there, was likely his much younger wife, Dorothy Benjamin. They had married in 1918, just three years before Caruso died.

This tragic love story inspired the verses of Dalla’s song “Caruso” which he wrote in in 1986, in the room in which Caruso had stayed many years before.

We can attempt a comparison of “Caruso” with “Ti Amo“, an equally famous Italian love song, but quickly find that Caruso is in a league of its own. Ti Amo by Umberto Tozzi (1977) is powerful in its melody and emotion, and it is a great song, but its lyrics let it down. It could be any lovers, anywhere. Its concepts are earthy, humdrum and focussed on the bedroom. There is something far deeper about Caruso: something Dantesque.

Love and Death

Caruso’s concatenation of death and love evokes Dante’s Vita Nuova, in which the beloved passes from life to death and in which love and loss are intimately entwined. As in Dante’s Commedia, love is the secret that transmutes loss into transcendence.

However also like Dante’s Vita Nuova, and so much else that male writers have written about love, the perspective, taken by Dalla, is that of a male voice speaking to or about the beloved. However, a quirk of Italian language, as noted by Laura Fabian, means that whether the singer is male or female, the words work almost equally well.

The opening words carry other echoes of Dante. Caruso begins by placing us in a dazzlingly beautiful place. Yet it is where the wind blows strongly: dove tira forte il vento. Soon we learn that an embrace follows tears: un uomo abbraccia una ragazza dopo che aveva pianto. We are lost in human anguish. Here Dante’s dark wood, and the midpoint of life, resonates. Quickly resolution follows. As in Canto 2 of Inferno where love moves Beatrice to send Virgil to redeem Dante, so also is love redemptive in Dalla’s Caruso. It redeems us from death. We are chained “ormai“; a word which evokes a forever “now”, resonant with regret. It could equally be translated as “alas”.

Also, like Inferno which is yet to really begin, as Dante is yet to reach hell in its opening cantos, Dalla’s Caruso also has a prelude. The song’s lyrics tell us that it begins again (“ricomincia il canto”) . Even the word canto, although it simply and primarily means song, reminds us of the cantos into which Dante divided his epic: each canto a song sung on street corners to passersby.

The connection of love, loss and beauty is of course about life itself. Although the following quote was minted in the 21st century, and is not a quote from Homer‘s Iliad, as prominently claimed across the internet, the words Brad Pitt’s Achilles utters in Wolfgang Peterson’s Troy (2004) are of the beauty and pathos of the human condition.

… any moment might be our last. Everything is more beautiful because we’re doomed. You will never be lovelier than you are now. We will never be here again.

Achilles in Troy 2004 cited in Troy, Chiasson, p 201

Even if Homer didn’t get this, Dante certainly did, including in his Canto of the doomed lovers Paolo and Francesca, whose tragic beauty he evokes in their eternal death. The same theme drives Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, as it drives Dalla’s Caruso.

Caruso weaves death throughout both its lyrics and in their resonances. Tears bring feelings of drowning. Death is better than the moon. And most evocatively, our lives are but the vanishing wake of a boat passing through a bay: Ti volti e vedi la tua vita, Come la scia di un’elica.

Caruso mentions only two places: Sorriento and America. And America too is poignant. It is a word of loss for all those who would never “Return to Sorrento” (another famous song set in the city). In the specific story of Enrico Caruso as a star of the opera, it is, as the song tells us, where, under the illusion of makeup, he loses his very self and becomes another.

There are many singers who have sung Caruso, including Lucio Dalla himself. Below are embedded to two music videos of Caruso. The first is Lucio Dalla’s official video, which is accompanied by images that tell the story of the song. The second is of Laura Fabian, whose interpretation perhaps best captures both the meaning and pathos of the song. The video is accompanied by an English translation.

Lucio Dalla Official Video of Caruso

Lara Fabian’s Interpretation of Caruso

Sources

Melisanda Massei Autunnali, Lucio Dalla e Sorrento – Il Rock i Tenori, Donzelli Editori, 2011

Charles C. Chiasson, Redefining Homeric Heroism in Wolfgang Peterson’s Troy, in Kostas Mirsiades (ed), Reading Homer in Film and Text, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press 2009, p 200

Images

Aida Giacchetti 1907 portrait by A. Galli. Aida Giachetti was Caruso’s first love. By Sailko – Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37889103

One Comment

Pingback: