When Malaria in Italy was a National Disease

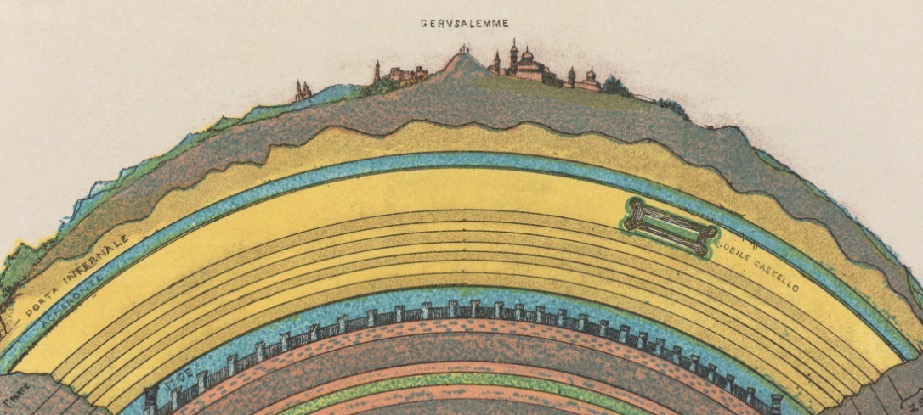

At the end of the 19th century, up to 20,000 Italians died every year from malaria and millions were infected. Even the word is Italian: “la mal’aria” – the bad air – a phrase to describe the mysterious and then unknown causes of the disease, which was attributed to the “bad air” of swampy ground. Malaria arrived in Italy in ages past, and was there when the ancient Greeks began to build their cities on Italy’s shores. The story of the effects of malaria is recorded in the collapse of the once flourishing city of Posaedonia (today Paestum). Founded about 600BC, its ancient Greek temples still draw tourists from around the world. The city is said to have collapsed at least in part because of malaria.

Before Italy became a single country, English gentlemen (and others) of the eighteenth century who took their Grand Tour to Italy would warn of the disease and give information on its treatment. The areas around Rome were particularly notorious, and to visit Rome in summer was to take your life in your own hands. Horace Walpole in 1740 wrote:

“There is a horrid thing called the malaria, that comes to Rome every summer, and kills one.”

J. A. H. Murray (editor), New English dictionary on historicalprinciples, Oxford, Clarendon

Press, 1908, vol. 6, p. 78.

When in 1792, Lady Palmerston and her husband were visiting Verona, he fell ill with intermittent fevers (a sure sign of malaria). Worried for her husband, she summoned a doctor.

“We sent for Doctor Farga, the most eminent physician of Verona. He found it to be a fever of the country; a kind of intermitting which in the autumn the inhabitants are extremely subject to […] He gave him the bark [quinine] […] It has agreed with him extremely.”

cited in Caroline Webb, Visitors to Verona: Lovers, Gentlemen and Adventurers, p 170

The ‘bark’ often known in English as Jesuit’s Bark, came from South America. The name gives credit to Jesuit missionaries (like the name cinchona does to a European lady). In truth the discovery was in fact indigenous knowledge of Peru. While malaria was gifted to the Americas by the arrival of Europeans, its treatment was affected by red or yellow bark of the native Cinchona tree. The healers of Peru already knew its efficacy in treating fevers and in their hands, it proved just as effective in treating the newly arrived malaria fever.

Despite the widespread knowledge of the existence of malaria and effective treatments for it, the impacts in Italy, especially among the poor, were poorly understood. This situation began to change after the unification of Italy. There was and remained for some decades a correlation between poverty and the spread of malaria as evidenced by researchers.

The disease inspired the nineteenth century realist writer Giovanni Verga to write a work titled Malaria.

“È che la malaria v’entra nelle ossa col pane che mangiate, e se aprite bocca per parlare, mentre camminate lungo le strade soffocanti di polvere e di sole, e vi sentite mancar le ginocchia, o vi accasciate sul basto della mula che va all’ambio, colla testa bassa. Invano Lentini, e Francofonte, e Paternò, cercano di arrampicarsi come pecore sbrancate sulle prime colline che scappano dalla pianura, e si circondano di aranceti, di vigne, di orti sempre verdi; la malaria acchiappa gli abitanti per le vie spopolate, e li inchioda dinanzi agli usci delle case scalcinate dal sole, tremanti di febbre sotto il pastrano, e con tutte le coperte del letto sulle spalle.”

“… malaria enters your bones with the bread you eat, and when you open your mouth to eat, and while you walk the road, suffocating in dust and sun, and your knees weaken, and when tiredness overtakes you on the back of a mule ambling along, its head lowered. Fruitlessly, like clambering sheep, the villagers of Lentini and Francofonte and Paterno seek refuge in the first hills that rise from the plain, and which surround it with orange groves, vineyards and evergreen orchards. Malaria seizes the people on roads emptied of inhabitants, it skewers them at the thresholds of their homes, whitened by the blazing sun, shivering with fever in their enormous coats and the blankets covering their shoulders.”

Verga, Malaria

The first to really draw a conclusion that malaria was a national problem and to seek to do something about it was the Italian parliamentarian, Luigi Torelli. In 1878 the construction of a railway in Sicily brought to consciousness the scale of the problem to national consciousness. 1455 of 2200 of the workers building the railway needed treatment for malaria. Torelli, who served on the Parliament’s Railway Commission made it a personal mission to understand and address the malaria problem.

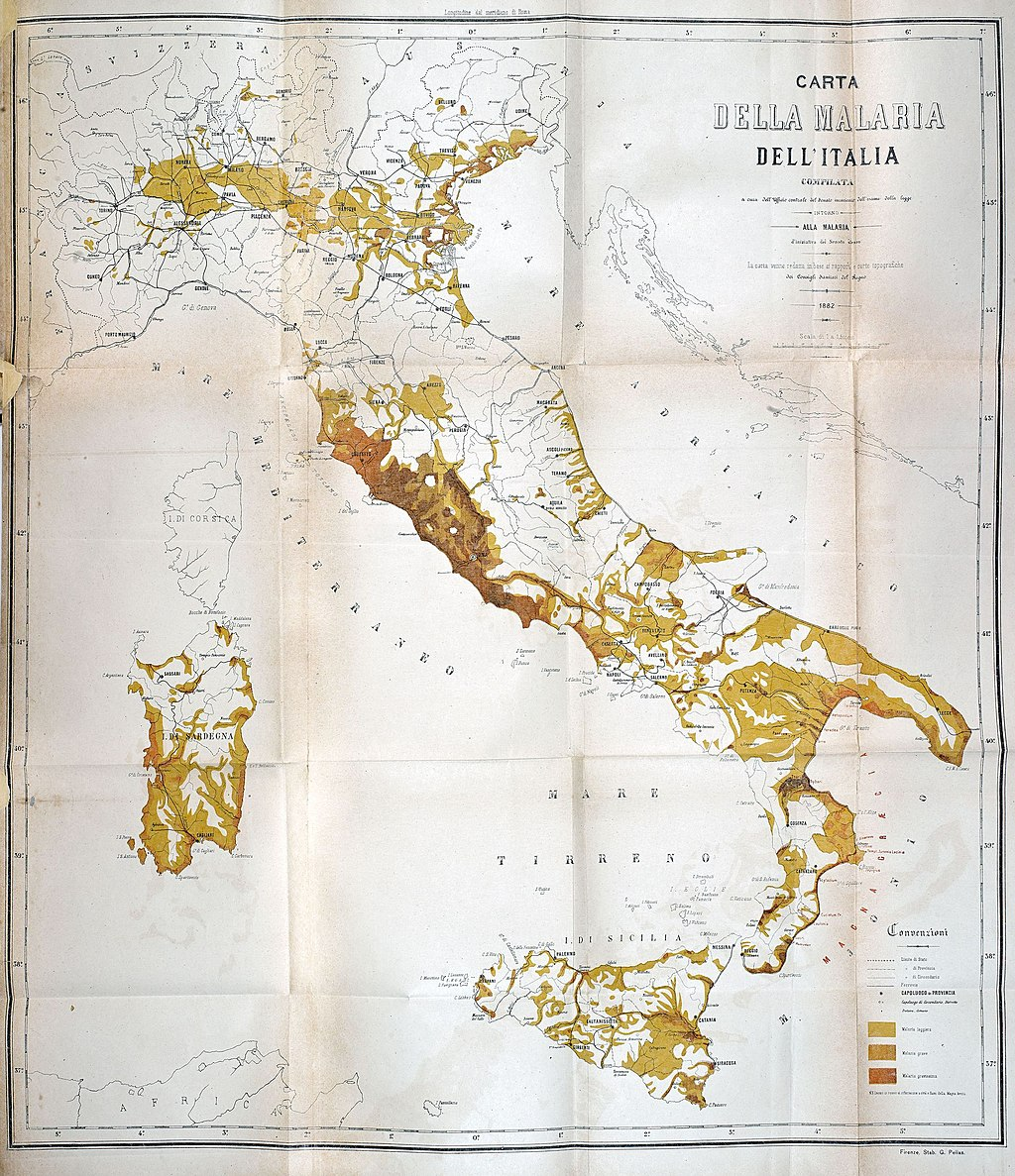

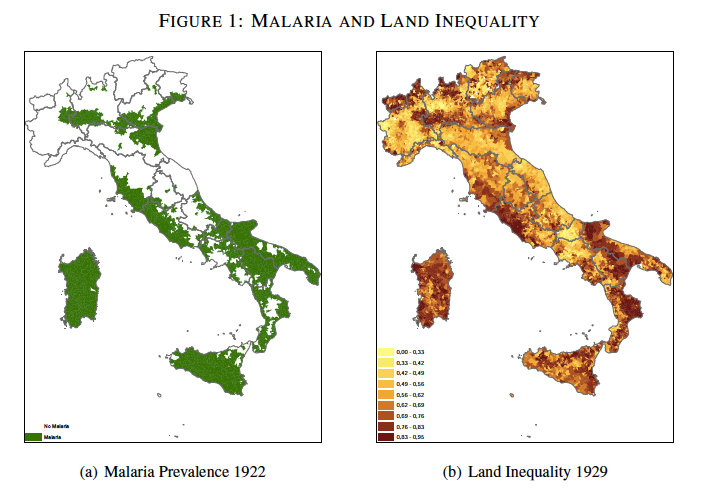

He sought information from around Italy, allowing him to publish the first ever map of malaria in Italy which he published in 1882. He sponsored bills in Parliament to encourage land reclamation (as malaria and swampy lands were so closely associated). He called for a “national war” on malaria.

The diseases became the subject of succeeding national reports eliciting reports such as the following from Sardinia.

“In the faces of our men, women, and children one can see the grayish pallor of repeated attacks of fever. It is well known that the dominant disease in many parts of the island is swamp fever, and that neglect and complications can make it serious or even fatal.”

Cited in Snowden, The Conquest of Malaria in Italy, p 11

That the scale of the problem was truly national was underlined by the fact that of Italy’s 8300 odd localities, over 3000 were malaria ridden. In areas struck by malaria, the already abysmal average life expectancy of 35.7 years for non-malarial regions at the beginning of World War 1, fell to 22.5 years. Most of the dead (as is still the case for malaria today) would have been infants and young children, implying a truly horrific toll of child mortality.

The provinces of Foggia and Rome, which were most afflicted had the lowest life expectancy. Such a toll of death was so profound as to leave a mark in the genome of many Italians. Six percent of Italians carry the Beta Thalassemia gene. Inheriting the gene from both parents’ results can cause severe disease or early death. Having the gene from just one parent usually involves no or minor symptoms through most of life, but it evolved in malaria endemic areas and is believed to protect the carrier against the effects of malaria.

The rich of Italy were well aware of the presence of malaria. For centuries, they had escaped the malarial dangers of summer by retreating to cooler hill country free of the disease. What is surprising is how many centuries it took before the powers that be in Italy to became aware that an enormous health crisis (borne primarily by the poor), surrounded them, and how long it took them to reach the conclusion that they should do something about it. Many of the poor themselves were unaware that they were ‘ill’ considering their malarial symptoms a normal condition of life. Mild fevers, distended bellies, fatigue and indigestion typical of the mild disease were not something that they recognised as needing treatment, as long as they remained able to work. Distrust of what had always been oppressive systems of government was another factor bringing suspicion on new government efforts to address the disease.

By the late nineteenth century however, the crisis was beginning to be understood in economic and well as health terms. Such a tide of illness and death undermined Italy’s desire to compete in agricultural production and had to be addressed for that reason as well. It was indeed oppressive conditions of agricultural production that contributed to the prevalence of disease. Where the disease was worst, inequality was highest with agricultural workers brutally exploited: insecure conditions of work, poor and unhygienic accommodation and poor access to health services. Malaria also began to be seen as one of the drivers of Italian emigration, which was so prominent in the early twentieth century, depriving the nation of needed workers. The military was affected as well with many called up for service simply unfit to serve and many already serving having to be discharged if they fell ill with malaria.

By the turn of the twentieth century the battle started in earnest and many others joined Torelli’s project. National campaigns to distribute quinine to the poor began, together with the establishment of rural clinics providing not only treatment for malaria, but also for other medical conditions. In some places carabinieri (Italy’s most professional police forces) were mobilised to assist doctors in meeting the enormous demands facing them. Medical professionals were inspired to join what had become a national crusade to eradicate malaria. Education campaigns were undertaken to overcome suspicion of government efforts, including in the new schools that were being established for agricultural workers and poor farmers. Land reclamation also proceeded apace, reducing the territory available to mosquitoes to propagate malaria, with the side benefit of opening new land to agricultural production. Chemical spraying was another strategy that was adopted.

Wars between men, as so often, undermined progress. The dislocations of World War 1 saw new outbreaks of malaria which reached epidemic conditions. World War 2 had similar effects.

The interwar years unleashed another kind of human disaster: the excesses and the logic of adulation of the Fascist leader demanded that the regime demonstrate its ability to exceed the success of previous regimes in the eradication of malaria.

One project involving the promotion of a scientist with Fascist credentials rather than scientific merit and led to a project in which Italians became experimental subjects of their own government. A control group of thousands was denied quinine and another group was injected with mercury as an unproven remedy promoted by this scientist. Apart from being unethical, the project was a failure.

A more well known project was the “bonifica integrale” of the Pontine Marshes – intended to showcase and pursue a Fascist vision. In propaganda terms it was a huge success. The methods used were those already developed before the Fascist era but carried to an extreme.

Tens of thousands of workers were sent in to clear the marshes, unprotected from the ravages of malaria which had depopulated the marshes: they were expendable foot soldiers of the new Fascist vision. Official statistics of their death and illnesses were not collected.

For a time, the project succeeded and as new settlers (selected on racial grounds) were moved into the new demonstration province of Littoria malaria fell (according to the official statistics) to negligible levels by 1939.

Mussolini’s decision to enter the war destroyed these hard won gains. By 1942 malaria was returning to the Pontine Marshes because a lack of workers meant drainage was no longer maintained. Even worse, after the surrender of Italy, and in the puppet regime nominally led by Mussolini, the Germans unleashed revenge on the Italians as well as furthering their military objectives. They re-flooded the Pontine Marshes in the rainy season with the calculation that it would unleash a devastating malaria epidemic (something known and planned for by their scientists), with the added benefit of providing a physical barrier to impede the allies.

They chose a specific combination of salty and fresh water (pumping sea water into the marshes) and destroying infrastructure to ensure that the mosquitoes that bred were the most virulent carriers of malaria. To ensure treatment would be difficult, the Germans also confiscated and hid a large stockpile of quinine that had been in held Rome. It was a diabolical deployment of biological warfare against a civilian population in an act of wartime revenge.

Further, countless bomb craters (many the result of allied bombing) provided fertile new places for infestations.

As a result, central and southern Italy experienced a return to malarial conditions during the war years.

Despite these horrors the long struggle was eventually to succeed. The engineering in the pontine marshes was sound and restored not long after the war. The postwar presence of the Americans led to reinvigorated campaigns against malaria using massive amounts of DDT across Italy, before its adverse effects were widely understood (although some scientists in the US were beginning to sound the alarm as early as 1944).

Finally, the many measures taken in fits and starts over generations were attaining success. By 1970, the World Health Organisation declared Italy free of malaria, more than eighty years after serious efforts to eradicate it began.

Sources

The Sacred Bark: A History of Quinine

Paolo Buonanno, Elena Esposito, Giorgio Gulino, Social Adaptation to Diseases and Inequality: Historical Evidence from Malaria in Italy, Barcelona GSE Working Paper Series Working Paper nº 1220, 2020

Crawford, Matthew James. The Andean Wonder Drug : Cinchona Bark and Imperial Science in the Spanish Atlantic, 1630-1800, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2016.

Majori G. (2012). Short history of malaria and its eradication in Italy with short notes on the fight against the infection in the mediterranean basin. Mediterranean journal of hematology and infectious diseases, 4(1), e2012016.

Pinto, Valeria Maria, et al. “Management of the aging beta-thalassemia transfusion-dependent population–The Italian experience.” Blood reviews 38 (2019): 100594.

David J. Roberts & Thomas N. Williams (2003) Haemoglobinopathies and

resistance to malaria, Redox Report, 8:5, 304-310, DOI: 10.1179/135100003225002998

Snowden, Frank. The Conquest of Malaria : Italy, 1900-1962, Yale University Press, 2006.

Giovanni Verga, Malaria in Verga Tutte le Novelle