The Flag without a Country: the Origins of the Italian Flag

The red, white and green of the Italian flag is well-known as a symbol for Italy. The Margherita pizza celebrates its colours. Its colours are displayed at every national celebration. But where does the flag come from and how did it come to be the national banner of Italy?

As with many good stories, the story of the Italian flag has a backstory. Sure it was carried by Giuseppe Garibaldi and his thousand red-shirts when they landed in Sicily in 1860, but the flag was already more 60 years old by then.

The backstory indeed doesn’t start in Italy at all. The resemblance of the Italian flag to the French national banner is no accident as we shall see, although an accident made it unique.

The French blue, white and red banner was a revolutionary banner, it began as a “cockade”, a round arrangement of pleated cloth that can be pinned to a hat or a coat. After a bit of fussing around as to the colours to be adopted, by 1792, the French officially settled on blue, white and red as their revolutionary cockade. In 1794 it was followed by the French flag in the same colours.

Meanwhile, in the Italian peninsula (Italy didn’t exist yet), these developments hadn’t gone unnoticed. Green had been one of the colours tried out in France but abandoned. It had the advantage that you could grab a green leaf and pin it on. As early as 1789 protesters against the various oppressive regimes in place in Italy began to use green as a symbol of revolution and of the new ideas contained in documents such as the French Declaration of the Rights of Man. News didn’t travel as well in those days as it does now and newspapers in Italy were incorrectly reporting that the colours of the French revolution were green, white and red. By August 1789 demonstrators were seen in Genoa using these colours on their cockade, by some accounts the first use of the colours of the Italian flag. Making virtue out of an accident of history, the green white and red stuck in revolutionary circles as a distinctive Italian symbol.

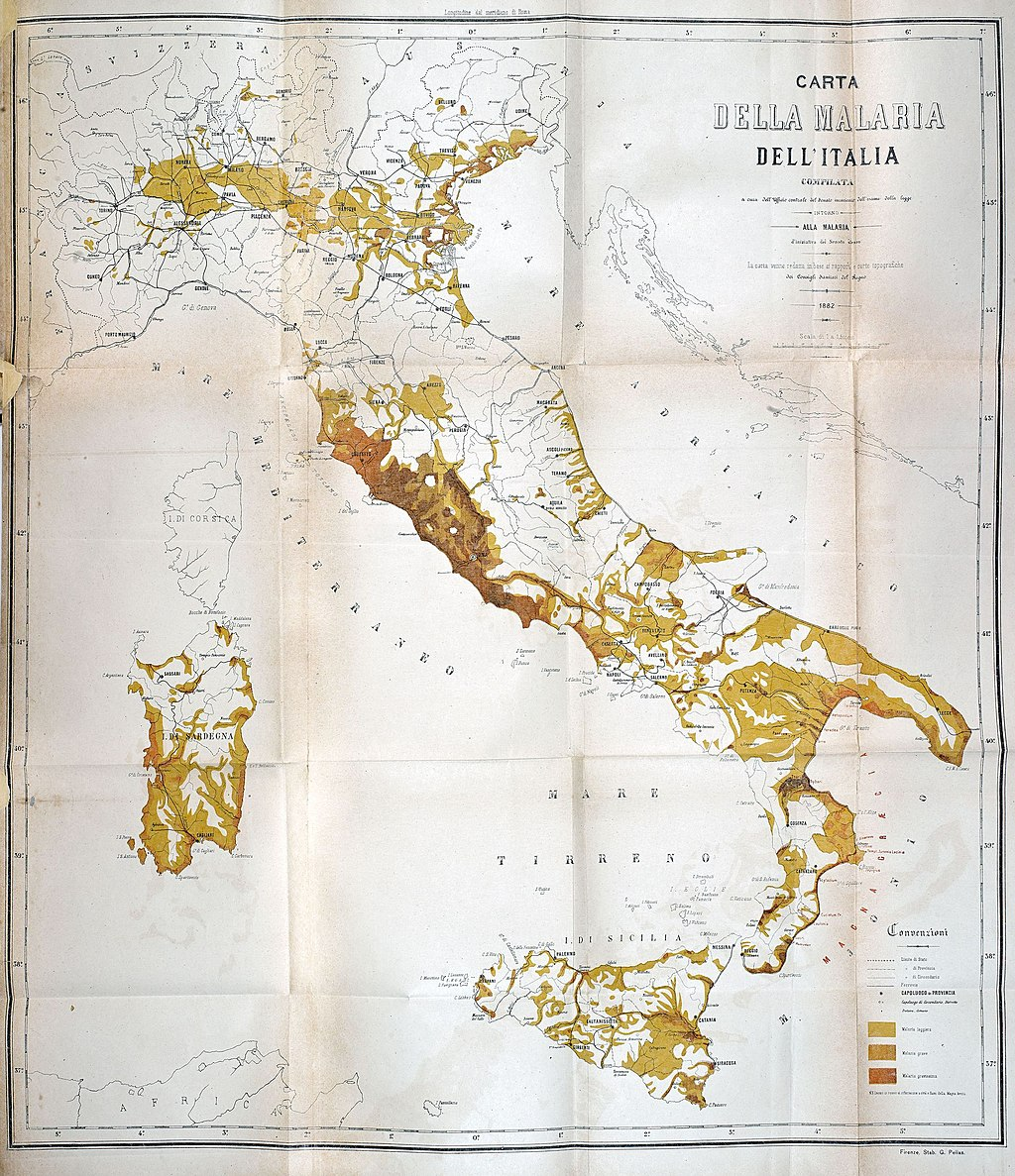

The patchwork of countries that inhabited Italy in this era included the Republics of Genoa and Venice, the Duchies of Modena, Parma and Milan, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Kingdom of Sardinia, the Papal States and the Kingdom of Naples (which included both southern Italy and Sicily). Bologna, the city of freedom, as proclaimed by the word “libertas” in its city shield, found itself a possession of the Pope. In 1794, an attempted insurrection there to overthrow papal rule used the colours of the Italian flag but ended in disaster. The leaders ended up in the notorious prison in Bologna called the Torrone. One was either murdered by cell mates or committed suicide after failing to escape. Another was publicly executed. Their father was tortured and killed by the authorities and his mother whipped through the streets and sentenced to life in prison.

But the winds of change were blowing and resistance to change would not last forever. The arrival of Napoleon in Italy in 1796, as a French general at the head of a French revolutionary army upended Italy and plunged it into a war that was spreading across Europe.

Pride of place at this point goes to the citizens of Reggio Emilia who successfully rose against their Duke. Similar to the Sicilian Vespers centuries before, the uprising started when a soldier of the Duke, mistreated a woman selling vegetables in the market. Citizens arose to defend her, and the uprising quickly spread and the Duke’s forces were driven from the city. The Duke himself fled with much of the country’s treasury to the Republic of Venice. The tree of liberty was raised in the city centre and its citizens formed a civic guard with the help of a small number of French grenadiers who had arrived there. This civic guard then attacked and drove out the Duke’s forces in the neighbouring castle of Montechiarugolo.

Napoleon meanwhile was sweeping through northern Italy, driving out Austrian forces present there. The French flag was still at this stage being used as the common symbol of the revolutionary era. The Italian colours were showing up in military banners such as that of the Lombard Legion, an Italian military unit allied with the French.

New, short-lived states started to spring up in these revolutionary areas. The Cispadane Republic was established in October 1796 covering the areas of Modena, Reggio Emilia, Ferrara and Bologna. Napoleon, in recognition of the symbolic importance of the events in Montechiarugolo, suggested the holding of a conference in Reggio Emilia. Bologna had already adopted the Italian tri-colour as its civic colours and as a ‘national’ symbol. At the conference in Reggio Emilia for the first time the green, white and red flag was adopted as the flag of a state. Unlike the future Italian flag, the stripes were horizontal, with a shield representing the four cities at its centre. In honour of this history the “Sala del Tricolore” celebrating the birth of the Italian flag is found in Reggio Emilia. Giuseppe Compagnoni who suggested the use of the flag to the convention is considered the “father” of the Italian flag.

But the revolutionary period was, well, revolutionary. The Cispadane Republic was replaced in 1797 by the Cisalpine Republic (now also covering Lombardy) and in 1798 for the first time the vertical green, white and red of the Italian flag became the flag of a state. It was not to last. The French were playing now a deciding role in Italian politics and the Cisalpine Republic become the Italian Republic which lasted from 1802-1805. It was then replaced by the Kingdom of Italy (with Napoleon as its king) which endured until Napoleon was defeated in 1814. These were states in north-eastern Italy. The flags of these states remained green, white and red, but the arrangement was completely changed and in the case of the Kingdom of Italy, included Napoleon’s imperial crest. (See the images below).

With the defeat of Napoleon, the Italian colours disappeared for a time. Many of the old states of Italy sprang back into being, although the two republics of Genoa and Venice disappeared forever. The Italian flag, however, would not die. It remained a revolutionary symbol. In the Austrian territories displaying the banner carried the death penalty. The flag was used during failed insurrections in the 1820s, 1830s and 1840s. In 1831 Giuseppe Mazzini adopted the flag for his revolutionary movement called “Young Italy”.

The revolutionary year of 1848 saw the banner again unfurled, this time in Milan. The Kingdom of Sardinia decided at this point to adopt the green, red and white, defaced with the shield of Savoy of it ruling house, as its national symbol. In 1849, Giuseppe Mazzini led a revolutionary government in Rome. Its symbol too was the Italian flag, although the republic was suppressed by invading French forces who were supporting the restoration of the Pope’s control of Rome.

We are now entering the era of the Risorgimento, when Italian unification was being advanced. The success of the Kingdom of Sardinia in is campaigns to liberate areas occupied by the Austrians and to absorb neighbouring Italian states into its territory assured the success of the Italian flag. By 1870, Italy was unified. The new Kingdom of Italy continued to use a green, white and red banner with the shield of Savoy. It remained the Italian flag until the end of World War 2. The flag of that era was also a symbol of Italian colonialism and later of fascism.

With a national referendum and the establishment of the Italian Republic on 13 June 1946, the Italian flag we know today was adopted. The shield of Savoy was removed. The old revolutionary green, white and red re-emerged and remains the flag of Italy today.