Romeo and Juliet Go Down to Egypt

As far as we know, the first recognisable version of Romeo and Juliet was written by Masuccio Salernitano, or, by his proper name: Tommaso Guardati. (His nickname just means: “Tommy of Salerno.”) In 1476, when he wrote his version of Romeo and Juliet, he didn’t use the names we now know today. Yet even though he calls the lovers “Mariotto and Gianozza,” and they lived in Siena instead of Verona, it’s clear these lovers are Romeo and Juliet.

The journey from Masuccio’s tale to that of Shakespeare passes through several versions. First, Luigi da Porto took the story and put it in Verona. He gave the lovers the names we know today. Then Matteo Bandello polished and extended the story (by a third) giving us its final Italian form. Next, Pierre Boaistuau translated the story into French, and then Arthur Brooke rendered his translation into English. Shakespeare, worked mainly from Brooke’s version, but also perhaps directly from the versions of Bandello and Da Porto and others. He converted the story into a play, and the rest is history. More than 200 years separates Masuccio’s version from the first printing of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

Romeo and Juliet – A rose by any other name …

Masuccio’s version of the story is not as polished as it later became. Writers that followed added dialogue and made the story longer, but the differences are fascinating. Juliet, or Gianozza, is not a Capulet. She is, as the story says, perhaps “di casa Saraceni”, “of the Saraceni house.”

Noting the epoch of the story, this is likely a surname. It indicates that our Juliet or Gianozza descends (on her paternal side) from a Muslim ancestor. Such a circumstance is not unique in Italy, there being many Italian surnames indicating Muslim, or North African, descent. Moro, Morelli, Musa and Pagano are just a few of many examples of such surnames. They speak to the connections between the northern and southern shores of the Mediterranean over many centuries. The Saraceni or Saracini surname is still quite common in Italy. Masuccio may have used it because it was the surname of a historical noble family of Siena.

Mariotto’s surname is “Mignanelli,”, rather than “Montecchio.” Mignanelli, was also a real surname among the nobles of the city. In fact, not long before the events in the story, a Beltramo Mignanelli, a merchant of a noble family of Siena, lived for many years in Damascus and later in Egypt. He wrote an eyewitness biography of Sultan Barquq of Egypt, the founder of the Burji Mamluk dynasty. This more Mediterranean orientation of the story, continues as we shall see below. But let us turn to the story as Masuccio tells it.

Masuccio Salernitano’s Romeo and Juliet

The lovers meet and fall desperately in love. To be together, they bribe an Augustinian monk to secretly marry them. Fate intervenes. Mariotto becomes involved in a fight with another citizen of Siena, killing the other. As in later versions of the story, he must flee the city. Mariotto confides in his brother to keep him informed of anything that might bear on Gianozza. Mariotto sails to Egypt to seek refuge in Alexandria. He has an uncle there, Ser Nicolo Mignanelli, who is a successful merchant. (These details are of course consistent with the historical Mignanelli mentioned above).

In any case, after Mariotto leaves for Egypt, Gianozza’s father decides that she must marry. Finding no escape, she turns again to the monk, who devises a potion that will put her to sleep and in seeming death for three days. This successful ruse sees her buried and after she wakes, she is smuggled out of the city dressed as a monk. She boards a ship for Alexandria from the Port of Pisano trying to reach Mariotto. Fate intervenes again. Various incidents of the journey delay her ship.

In the meantime, Mariotto’s brother, believing Gianozza dead, writes to Mariotto in Alexandria to share the bitter news. The caravel on which the letter travelled, sails on quickly and Mariotto receiving his brother’s letter, and hearing no other news, takes it for certain that Gianozza is dead. So taking a Venetian galley for Italy, he returns by way of Naples and disguised as a pilgrim makes his way to Siena. There he makes his way to Gianozza’s tomb, weeping and wishing he could enter the tomb with her. As fate would have it, he is discovered. Despite the tears of the ladies of the city, who judge him to be the truest lover who ever lived, he is put to death.

The unfortunate Gianozza meanwhile, finally arrives in Alexandria and finds the house of Mariotto’s uncle. He receives her kindly and helps her. She dresses once more in disguise as a man, and he accompanies her back to Siena, where she hides in an estate which he owns. There she learns the heartrending news that only three days earlier, Mariotto had been decapitated. Despite all Ser Nicolo can do, the disconsonsolate Gianozza is so heart broken that after some days she dies of grief.

Of course, although recognisable as ‘Romeo and Juliet‘ many things are different in the story. The essentially core of desperate lovers who end up giving their lives for each other, is there. The role of a monk who helps with a sleeping potion is also present. The flight is to a different city and the miscommunication between them is yet another common element. Of course we also see many differences.

Romeo and Juliet’s Compass Shifts Northward

The Mediterranean orientation we see in Masuccio Salernitano’s version was to disappear in later versions. In the era in which he wrote, the Mamluks were still and independent kingdom. The kind of maritime commerce in Egypt that the story fictionalises was commonplace. So commonplace, as to be entirely believable for the story. Siena was still an independent republic, although the Black Death so much affected it, that eventually its rival Florence, absorbed it.

Luigi da Porto wrote the next version of the story in 1527, fifty years after Masuccio’s. The world had changed in those fifty years. The Ottoman Empire had been growing in power for generations, the conquest of Constantinople in 1453 was just the beginning. By 1517 it had conquered Mamluk Egypt. From that time, Mediterranean trade to the East was an Ottoman monopoly.

Other powers were rising. In 1492, the Spanish began to colonise North America. Spain had become a single kingdom and a growing empire, which included parts of Italy. American gold was financing its power. In 1498, the Portuguese Vasco da Gama sailed around Africa from Europe to India. France also was a formidable rising power across the Alps. The Ottomans meanwhile continued to press westward in the Mediterranean. All these developments spelled the beginning of the end for the maritime trading empires of Italy. From 1494, France and Spain began to play out a series of great power wars in Italy, taking turns in conquering this or that part of the peninsula. Charles V, the new Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain controlled much of Europe and in 1527 his troops sacked Rome.

Luigi da Porto’s lived this new world. Himself a citizen of the now fading Venetian Republic, hailing from the town of Vicenza only a few kilometers from Verona, he shifted the story there. Trade flowed down the River Adige to Verona and travellers arrived along its valley from Germany beyond the Alps. The faraway places of the Mediterranean and the trade across it disappeared in his new Romeo and Juliet. Da Porto begins the story with a frame tale. Like other writers he pretends that he has heard the story told to him. A fellow soldier with whom on the road, to pass the time, and lighten the burdens of war, recounts to him the story of the tragic lovers.

Layla and Majnun

Of course, love stories are found in all cultures. It is no surprise that Romeo and Juliet is found in Arabic translation and is well-known in the Egypt where Masuccio Salernitano partly sets the story. One researcher suggests that there are resonances of Sufi love themes in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Certainly, stories from the East made their way into Italy and beyond. Boccaccio’s collection includes many, which he re-tells in Italian. In Shakespearean England, the Fables of Bidpai or the Moral Philosophy of Doni, translated by Sir Thomas North in 1570, brought Kalilah and Dimnah to England. That tale too came from India, through Arabic, Farsi and Italian translations on its journey to England.

However Layla and Majnun is the Middle East’s Romeo and Juliet. The story comes originally from the Arabian peninsula and is an ancient tale. “Majnun”, a nickname literally meaning “mad,” is about the pining love of Qays (Majnun) who can never be united with his beloved Layla. They are separated by an arranged marriage, forced on Layla by her family. (Similar to elements we find in Romeo and Juliet). Majnun seeks Layla ceaselessly but is never able to reach her. In the end he pines away. Layla, after her husband’s death, seeks out Majnun’s grave and mourns herself to death at his graveside (a similarity with Masuccio Salernitano’s Gianozza). The story has of course other shared themes with Romeo and Juliet. The most famous version is an epic poem by the Persian poet Nizami. However like Romeo and Juliet, Layla and Majnun has been translated into many languages. Perhaps the most striking resonance between the two love stories, is the theme of love madness. Returning to the Sufi themes, love of Layla, “the beloved,” is often understood as representing love for the divine. That idea certainly made its way to Europe. We find it in Dante’s divinisation of the feminine figure Beatrice, and we can be sure that it is an idea that Islamic civilisation contributed to Europe. A beautiful version of the story in its mystical context is recounted by Baha’u’llah, the founder of the Baha’i Faith in his work: The Seven Valleys:

It is related that one day they came upon Majnún sifting the dust, his tears flowing down. They asked, “What doest thou?” He said, “I seek for Laylí.” “Alas for thee!” they cried, “Laylí is of pure spirit, yet thou seekest her in the dust!” He said, “I seek her everywhere; haply somewhere I shall find her.”

Baha’u’llah, The Seven Valleys

Notes

The original of Masuccio Salernitano’s Mariotto e Gianozza can be read at this link: https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_21dCU4chVzoC/page/357/mode/2up (original)

The Legend of Romeo and Juliet explores the history of the story through numerous versions.

Image

Cupola of the Cathedral of Siena, author’s image.

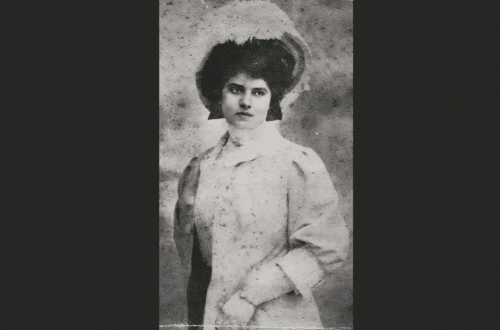

Layla Weeping at Majnun’s Tomb by Sharada Ukil, 1927, public domain image