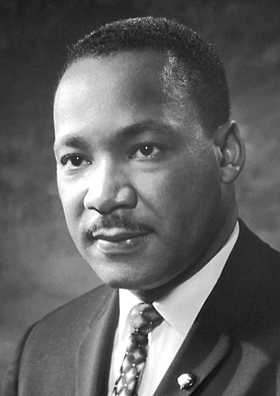

The Peace Advocacy of Martin Luther King (Part 4 of 4)

To appreciate Martin Luther King’s thoughts on peace, we must understand his thoughts about the relationship between human beings.

He saw all human beings as caught “in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.” He expands on this thought in his 1964 speech, “The American Dream”.

All I’m saying is simply this, that all life is interrelated. And we are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny — whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. For some strange reason I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be, and you can never be what you ought to be until I am what I ought to be. This is the interrelated structure of reality. … I think this is the first challenge and it is necessary to meet it in order to move on toward the realization of the American Dream, the dream of men of all races, creeds, national backgrounds, living together as brothers.

In this context he recasts the American Dream as a universal dream.

I would like to start on the world scale, so to speak, by saying if the American Dream is to be a reality we must develop a world perspective. It goes without saying that

the world in which we live is geographically one, and now more than ever before we are challenged to make it one in terms of brotherhood. … through our scientific genius we have made of this world a neighborhood, and now through our moral and ethical commitment, we must make of it a brotherhood. We must all learn to live together as brothers or we will all perish together as fools. This is the challenge of the hour. No individual can live alone, no nation can live alone. Somehow we are interdependent.

The implications of these insights on the nature of human relationships lead to his advocacy of peace in the context of the Vietnam War.

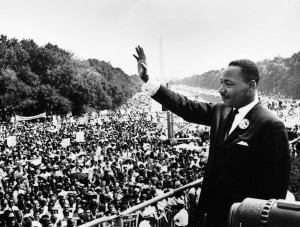

In April 1967 in a speech titled “Beyond Vietnam”, he outlined the reasons why he felt he had to speak out on the war in Vietnam.

“Over the past two years, as I have moved to break the betrayal of my own silences and to speak from the burnings of my own heart, as I have called for radical departures from destruction of Vietnam, many persons have questioned me about the wisdom of my path.”

He offered seven reasons for his opposition.

First was the adverse impact of warfare on his efforts to alleviate poverty of African-Americans.

There is at the outset a very obvious and almost facile connection between the war in Vietnam and the struggle I and others have been waging in America. A few years ago there was a shining moment in that struggle. It seemed as if there was a real promise of hope for the poor, both black and white, through the poverty program. … Then came the buildup in Vietnam, and I watched this program broken and eviscerated as if it were some idle political plaything on a society gone mad on war. And I knew that America would never invest the necessary funds or energies in rehabilitation of its poor so long as adventures like Vietnam continued … So I was increasingly compelled to see the war as an enemy of the poor and to attack it as such.

Second was the direct harm of the war on the lives of African American young men and families.

it became clear to me that the war was doing far more than devastating the hopes of the poor at home. It was sending their sons and their brothers and their husbands to fight and to die in extraordinarily high proportions … We were taking the black young men … and sending them eight thousand miles away to guarantee liberties in Southeast Asia which they had not found in southwest Georgia and East Harlem. So we have been repeatedly faced with the cruel irony of watching Negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools.

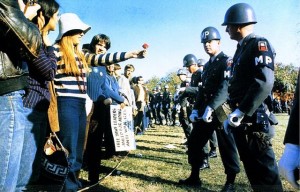

Third was the need to speak against violence as a solution to problems.

As I have walked among the desperate, rejected, and angry young men, I have told them that Molotov cocktails and rifles would not solve their problems. … But they asked, and rightly so, “What about Vietnam?” They asked if our own nation wasn’t using massive doses of violence to solve its problems, … Their questions hit home, and I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today: my own government.

Fourth was the American Dream, that any solution must realise that dream in larger proportions.

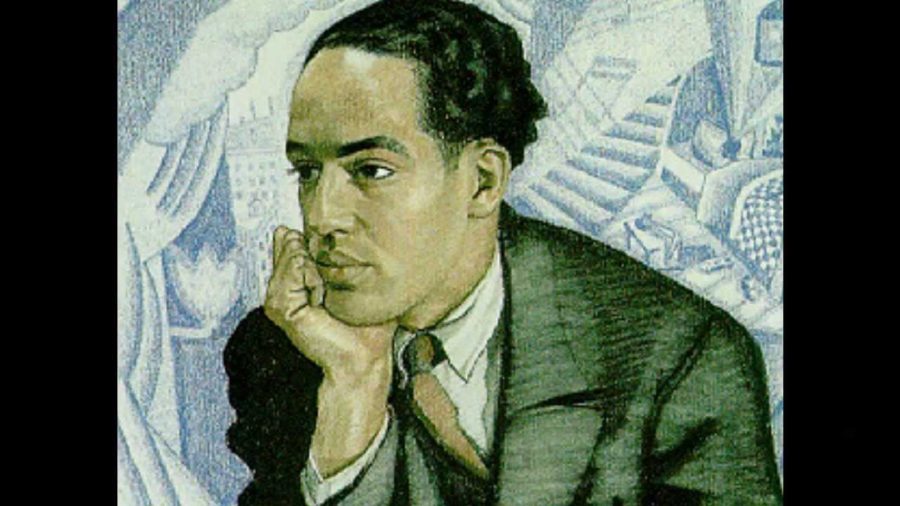

In a way we were agreeing with Langston Hughes, that black bard from Harlem, who had written earlier:

O, yes, I say it plain,

America never was America to me,

And yet I swear this oath—

America will be!Now it should be incandescently clear that no one who has any concern for the integrity and life of America today can ignore the present war. … America’s soul … can never be saved so long as it destroys the hopes of men the world over. So it is that those of us who are yet determined that “America will be” are led down the path of protest and dissent, working for the health of our land.

Sixth, he cites his commitment as a Christian minister, in addition to the charge laid on him by the Nobel Peace Prize.

To me, the relationship of this ministry to the making of peace is so obvious that I sometimes marvel at those who ask me why I am speaking against the war. … Have they forgotten that my ministry is in obedience to the one who loved his enemies so fully that he died for them?

Finally he cites the oneness of humanity, the theme of “brotherhood”.

Beyond the calling of race or nation or creed is this vocation of sonship and brotherhood. Because I believe that the Father is deeply concerned, especially for His suffering and helpless and outcast children, I come tonight to speak for them. This I believe to be the privilege and the burden of all of us who deem ourselves bound by allegiances and loyalties which are broader and deeper than nationalism and which go beyond our nation’s self-defined goals and positions. We are called to speak for the weak, for the voiceless, for the victims of our nation, for those it calls “enemy,” for no document from human hands can make these humans any less our brothers.

Here his words, in respect of how we view our fellow human beings, recall words he wrote to his fellow Ministers from his prison cell in Birmingham.

Segregation, to use the terminology of the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber, substitutes an “I-it” relationship for an “I-thou” relationship and ends up relegating persons to the status of things.

Later in his speech he turns to the question of values, calling for a “revolution of values”.

I am convinced … we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights, are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.

He continues on poverty:

A true revolution of values will soon look uneasily on the glaring contrast of poverty and wealth.

On war:

A true revolution of values will lay hand on the world order and say of war, “This way of settling differences is not just.”

War is not the answer.

Finally the capstone of the revolution in values for which he calls is an expansion of loyalties from the particular to the universal:

A genuine revolution of values means in the final analysis that our loyalties must become ecumenical rather than sectional. Every nation must now develop an overriding loyalty to mankind as a whole in order to preserve the best in their individual societies.

It is a re-orientation to humanity as a whole as the highest value. It is not however a vague “emotional bosh” he means:

This call for a worldwide fellowship that lifts neighborly concern beyond one’s tribe, race, class, and nation is in reality a call for an all-embracing and unconditional love for all mankind. This oft misunderstood, this oft misinterpreted concept, … has now become an absolute necessity for the survival of man. When I speak of love I am not speaking of some sentimental and weak response. I’m not speaking of that force which is just emotional bosh. I am speaking of that force which all of the great religions have seen as the supreme unifying principle of life. … We can no longer afford to worship the god of hate or bow before the altar of retaliation. The oceans of history are made turbulent by the ever-rising tides of hate.

It is impossible to separate Martin Luther King’s advocacy of peace from the other aspects of his thought, they are part of a the same cloth, understood from different perspectives. In his views on war, he still speaks primarily to the same audience: the “oppressed” who have come on the journey of civil rights, but the audience is now re-conceptualised as the “privileged”, members of a society benefiting from wider global inequities. Here he thus speaks with the same self-critical voice that the earlier abolitionists of the slave trade spoke.

When we consider his words, we see that they are far more than rhetoric. They communicate the insights of a complex world-view. We see that his words have considerable courage. Of course to oppose segregation itself took great courage. To speak out against the Vietnam War, when he did, was an act of courage. To speak out for a wider loyalty to humanity as a whole was an act of courage. It is evident that he saw these stances as necessary for the welfare of those he served, and the dispossessed in the world as a whole.

As a human rights advocate he spoke for peace in a time of war. Almost half a century later the world remains beset by wars. The same concerns of the adverse impacts of war on the attainment of human rights in his time, remain pertinent. It is moreover hardly possible to separate the cause of peace from the cause of human rights. They are in reality, one and the same cause. For human rights workers, peace is a necessary precondition of progress in human rights. When fear and war seizes the public mind, human rights are stalled for years or decades and often hard won principles are torn to shreds. In the case of the abolition of the slave trade, the Napoleonic Wars delayed abolition for 20 years. In conditions of war human rights cannot progress. Appallingly, in the 21st century, while borders, barbed wire and walls, are erected with ever greater efficiency between people, the boundaries between war and peace have virtually broken down. This represents an existential threat to human rights.

Finally, few seem to appreciate the importance of what Martin Luther King communicated when he spoke of “wider loyalties”, the deeper “dream”, the journey which is still incomplete. For reasons which are mystifying, the establishment of a world society based on ‘love – agape’ between human beings, are rarely considered a ‘serious’ contribution to public policy.

Few advocate for the “revolution in values” which Martin Luther King espoused. It is difficult to find those who take the brother and sisterhood of humankind seriously in our halls of learning. Regretfully. Rarely do the words of our political leaders rise to such a noble orientation worthy of human dignity. Sadly. Even in the advocacy of those who stand for and devote their lives to human rights, often the theme of ‘brother/sisterhood’ falls far behind in a race in which equality and freedom are out in front, and brother/sisterhood almost forgotten.

If human rights is to achieve its purpose in the world, this third theme of human rights must be recaptured. If Martin Luther King is right, it must be brought to the centre of human rights advocacy, with all that implies.