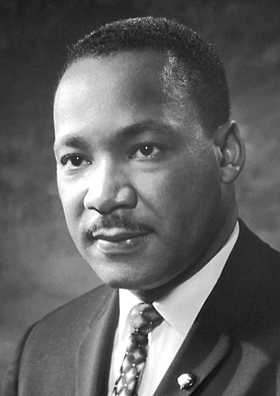

Martin Luther King Jr – Civil Rights Leader and Peace Advocate

Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his life for the poor of the world, the garbage workers of Memphis and the peasants of Vietnam. The day that Negro people and others in bondage are truly free, on the day want is abolished, on the day wars are no more, on that day I know my husband will rest in a long-deserved peace.

—Coretta King

This article is part of a series on human rights forebears. Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. lived a life beyond the ordinary and writing about him is challenging. His life made the world that came after him better. This article will not do justice to his contribution. Nonetheless, as with previous articles, the aim is to learn what Martin Luther King teaches us for the human rights issues of today. The focus of this article will be on Martin Luther King’s thought, mainly as expressed in his recorded speeches, rather than on the civil rights movement as a whole.

In popular media, Martin Luther King is projected almost solely as a leader of the civil rights movement. This of course he was, and it was central to his work. But the picture is incomplete. Other aspects of his thought include the spiritual reservoir from which he drew; his advocacy of nonviolent methods; his profound belief in the interconnectedness of all human beings and his advocacy of peace.

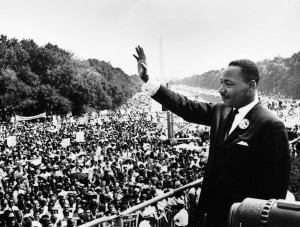

He is a figure who stands at the birth of the world in which we now live. His life and work marked a watershed. In our world, racism is a condemned ideology. We are so used to this reality that we may unconsciously project our realities back to the world as it was in his time. Over and over we hear Martin Luther King’s words echoed in our popular media: “I have a dream“. We enjoy the benefits of the translation of Martin Luther King’s dream into reality. As a civil rights leader, he worked for, and gave his life to end racial segregation and racism in the United States. His work was part of a global trend which has rejected the ideology of racism. While racism still exists in the world, while it is still virulent and hateful, it is an ideology of the past, not the future.

Martin Luther King’s human rights work was deeply motivated by what he drew from his personal history and commitment as a Christian leader. This source can be seen in how he conceived of the struggle to contribute to a more just world, and as a spiritual reservoir which gave strength and resilience to his work. His adoption of the methods of nonviolence to pursue civil rights goals is an important aspect of what he did. A further aspect of his life that attracts less attention than it ought, is his advocacy of peace. This is one of the main pieces of unfinished work which he left us. While we may be tempted to think of these dimensions as separate, it is likely that for him, they were part of one integral whole. All of these aspects belong together. For example, his advocacy for peace built on his advocacy for human rights, and he explained it, as a necessary extension of the work he did in the civil rights movement.

Martin Luther King lived from 1928 until his assassination on 4 April 1968. His death, along with the killings of John and Robert Kennedy in the space of a few years brought to an end an era of visionary progressive leadership in the United States.

Before looking further at his life and thought, a review of the changes associated with the Civil Rights Movement, give a sense of the scope of the transformation to which Martin Luther King contributed. The following are pieces of legislation designed to address the injustices that were among the fruits of the civil rights movement.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, colour or national origin in employment and public accommodation. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 protected the right of all citizens to vote. The Immigration and Nationality Services Act of 1965 opened immigration to the United States to non-Europeans and the Fair Housing Act of 1965 banned discrimination in the sale and rental of private housing.

Each item of legislation addressed a real and deep field of injustice, most that were particularly experienced by African Americans. Martin Luther King’s words capture some of these profound denials, in ways that such a list can never capture.

Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, “Wait.” But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate filled policemen curse, kick and even kill your black brothers and sisters; when you see the vast majority of your twenty million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society; when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six year old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky, and see her beginning to distort her personality by developing an unconscious bitterness toward white people; when you have to concoct an answer for a five year old son who is asking: “Daddy, why do white people treat colored people so mean?”; when you take a cross county drive and find it necessary to sleep night after night in the uncomfortable corners of your automobile because no motel will accept you; when you are humiliated day in and day out by nagging signs reading “white” and “colored”; when your first name becomes “nigger,” your middle name becomes “boy” (however old you are) and your last name becomes “John,” and your wife and mother are never given the respected title “Mrs.”; when you are harried by day and haunted by night by the fact that you are a Negro, living constantly at tiptoe stance, never quite knowing what to expect next, and are plagued with inner fears and outer resentments; when you are forever fighting a degenerating sense of “nobodiness”–then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait.

The oppression the civil rights movement addressed was as pervasive and profound as any in human history.

As a civil rights leader, Martin Luther’s achievement is of course captured in his “I have a dream” speech of 28 August 1968. It is so well-known that it hardly needs repetition. As a speaker he was masterful, but that mastery was not only in respect of words, it was in respect of ideas. He framed the civil rights movement as a universal movement for the fulfilment of the accepted but unrealised values of the society to which he belonged. In doing so he enabled those around him to see and conceive of the civil rights movement not as an African-American movement solely concerned with African-American rights – but rather a universal movement concerned with the realisation of deeply shared human values and aspirations. In its fullest sense his vision of justice included all human beings.

Martin Luther King Jr. – What role did Christianity play in his civil rights advocacy?

Martin Luther King Jr. was born in Atlanta Georgia, the second son of Martin Luther King Sr. and Alberta Williams King.

Martin Luther King Jr. was by vocation a Baptist minister. He was in the fourth generation of his family to take up this vocation. It is impossible to fully appreciate Martin Luther King’s work without understanding the role that Christian thought and inspiration played in his advocacy of human rights.

Martin Luther King’s letter from a Birmingham prison to fellow Christian clergymen gives insight to the role his religious commitment played in generating and sustaining his commitment to work for justice. Further, the people from whom he came, the African Americans who struggled against centuries of slavery and racism, drew from deep spiritual and human reservoirs in the long and bitter journey from slavery, through oppression and segregation, before the civil rights reforms were won.

In setting out why he was in Birmingham he explicitly drew on a ‘prophetic role’.

“I am in Birmingham because injustice is here. Just as the prophets of the eight century B.C. left their villages and carried their “thus saith the Lord” far beyond the boundaries of their home towns … so I am compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my home town.”

In explaining the nonviolent methods he practised, criticism of which he was responding to, he wrote:

“We have waited more than 340 years for our constitutional and God-given rights.”

He drew on biblical precedents for civil disobedience to the law, “on the ground that a higher moral law was at stake“. Human rights, as he conceived them, do not depend on the decision of any human agency. As a consequence, they can never be overridden by any human decision. It is a perspective which in the final analysis places human rights beyond the reach of any tyrant, no matter how powerful, and beyond the reach of any rationalisation offered by the powerful that claims a justification for the oppression of human beings.

In thinking about Martin Luther King’s Christianity, we would again miss something significant to his human rights advocacy if we didn’t consider how his spiritual practice was engaged in that work. The role that prayer played in Martin Luther King’s work, is captured in a recollection from his wife Coretta King.

Prayer was a wellspring of strength and inspiration during the Civil Rights Movement. Throughout the movement, we prayed for greater human understanding. We prayed for the safety of our compatriots in the freedom struggle. We prayed for victory in our nonviolent protests, for brotherhood and sisterhood among people of all races, for reconciliation and the fulfillment of the Beloved Community.

For my husband, Martin Luther King, Jr. prayer was a daily source of courage and strength that gave him the ability to carry on in even the darkest hours of our struggle.

I remember one very difficult day when he came home bone-weary from the stress that came with his leadership of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. In the middle of that night, he was awakened by a threatening and abusive phone call, one of many we received throughout the movement. On this particular occasion, however, Martin had had enough.

After the call, he got up from bed and made himself some coffee. He began to worry about his family, and all of the burdens that came with our movement weighed heavily on his soul. With his head in his hands, Martin bowed over the kitchen table and prayed aloud to God: “Lord, I am taking a stand for what I believe is right. The people are looking to me for leadership, and if I stand before them without strength and courage, they will falter. I am at the end of my powers. I have nothing left. I have nothing left. I have come to the point where I can’t face it alone.”

Later he told me, “At that moment, I experienced the presence of the Divine as I had never experienced Him before. It seemed as though I could hear a voice saying: ‘Stand up for righteousness; stand up for truth; and God will be at our side forever.'” When Martin stood up from the table, he was imbued with a new sense of confidence, and he was ready to face anything. (Coretta King – Standing in the Need of Prayer)

If one happens not to share Martin Luther King’s faith, what meaning can be drawn from what is described here? Within the act of prayer, part of what is described is Martin Luther King’s search for and discovery of knowledge in a time of deep uncertainty.

Another article considers the semi-autobiographical work, The Strange Alchemy of Life and Law by, Justice Albie Sachs. From South Africa, much of Justice Sach’s life has also been devoted to human rights through the struggle against apartheid, as well as to law. Justice Sachs describes himself as Jewish but non-religious: “not practising in any way”. Yet he states in his book: “I did in fact have a strong set of beliefs, my own world view, in many ways a deeply spiritual one with overwhelming ethical implications.” Speaking of solving problems in the law, he speaks about moments of inspiration as being the most creative and productive: “only when I had been close to being in what my Buddhist friends would call a transcendental meditational state, would these formulations emerge, as if from nowhere … it so happened that the first three times I was cited in foreign jurisdictions, the formulations had all come to me at moments when my brain had been least engaged in hard legal reasoning”. Looked at in ways that transcend mere words, there is much that is common in the human experience. The inner resources that Martin Luther King drew upon do not depend on how we choose to describe ourselves nor on the particular model of reality we may hold. They likely do depend on some form of engagement with our inner “spiritual” life; however we might describe it.

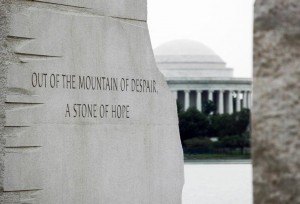

Most poignantly, the deep spirituality of Martin Luther King’s journey, is captured in the final words of the speech he delivered the evening before his murder. There were fears that evening. Threats had been made. He spoke of how happy he was to live in the time of the civil rights movement, having survived an earlier assassination attempt, and having seen the victories that had been won. How happy he was to have lived long enough to undertake the work he felt he had to do, and had now completed. In his last words he was a Moses to his people.

“Well, I don’t know what will happen to me now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t matter what happens to me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we, as a people will get to the promised land. And I’m happy tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

The spiritual roots of human rights on which he drew, are also seen in his speech titled “the American Dream”, delivered in 1964, where he spoke on the concept of rights, as found in the U.S. Declaration of Independence. He says of its well known opening phrases affirming the core values of human rights that, “This is a dream.” He means it is a dream that neither existed at the time the Declaration was originally written, nor did it exist in his own day. He identifies as distinctive of this dream that:

“It says that each individual has certain basic rights that are neither derived from nor conferred by the state. They are gifts from the hands of the Almighty God.”

In his speech in 1964 accepting the Nobel Peace Prize his words speak of the power of “faith”. In this case his words are not so much addressing “religious” faith, as addressing a “faith” that sustains the struggle against oppression, even in the direst circumstances.

“I refuse to accept the view that mankind is so tragically bound to the starless midnight of racism and war that the bright daybreak of peace and brotherhood can never become a reality. …

“I still believe that mankind will bow before the altars of God and be crowned triumphant over war and bloodshed … I still believe that we shall overcome.

“This faith can give us courage to face the uncertainties of the future. It will give our tired feet new strength as we continue our forward stride toward the city of freedom. When our days become dreary with low-hovering clouds and our nights become darker than a thousand midnights, we will known that we are living in the creative turmoil of a genuine civilization struggling to be born.”

These are the words of a man and a people whose faith have sustained them through centuries of oppression.

In international fora, and in the 21st century, human rights work is generally carried on without reference to any ‘higher authority’.

In part, this is a consequence of the need for universality – the necessity of adopting and speaking a language and concepts that are accessible for all human beings irrespective of historical background and irrespective of belief. Of using language that does not exclude the dreams of any human being for justice. Thus when, in 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights re-expressed “the dream”, it did not mention “God”. Not because faith was not important to a number of those involved in the creation of the Declaration, but because those involved felt this new language should be a wider dream inclusive of all human beings irrespective of “belief”.

Their insight was of course right.

However, a heavy price is paid if, from a justifiable concern for universality, we disconnect human rights from its genuine human history.

One price, is the unmooring of human rights from the lives of the human beings who gave us human rights. Many, as a matter of historical fact, were motivated by their religious beliefs. Many were not. But human rights cannot be understood if the actual stories of the human beings involved are not told and re-told. Each story gives us new insight. Where that story includes faith, it requires neither minimisation nor excuse. Rather the insights that they offer need to be gathered and contributed back into the flow of today’s and tomorrow’s human rights work. Without these human stories, the roots of human rights are stripped of their humanity. It was real human beings, with deep and complex motivations, who gave us human rights. By walking alongside them through their stories as they struggle to realise human rights, we learn what universality of human rights means far more deeply than from any philosophical argument.

Further if we do not tell the real history, other narratives are substituted that impoverish human rights history. Paul Gilroy in his oration Race and the Right to be Human has captured this well.

We meet this evening close to the 61st anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. As it became popular and influential, the political idea of human rights acquired a particular historical trajectory. The official genealogy it was given is extremely narrow. The story of its progressive development is usually told ritualistically as a kind of ethno-history. In that form, it contributes to a larger account of the moral and legal ascent of Europe and its civilizational offshoots.

The bloody histories of colonization and conquest are rarely allowed to disrupt that linear, triumphalist tale of cosmopolitan progress. Struggles against racial or ethnic hierarchy are not viewed as an important source or inspiration for human rights movements and ideologies. Advocacy on behalf of indigenous and subjugated peoples does not, for example, merit more than token discussion as a factor in shaping how the idea of universal human rights developed and what it could accomplish.

Needless to say, this substitute history is deeply inaccurate. In words that Martin Luther King might use, the “ought” of human rights and human aspiration is displaced and substituted by the “is” of the status quo. This status quo was, in Martin Luther King’s time, and remains in many ways in our own, profoundly unjust. To let an unjust present appropriate and clothe itself in human rights, places a high and unjustified barrier in the way further human rights progress. It disempowers those who like Martin Luther King, seek a better future than today.

Thirdly there is a specific methodology which human rights forebears like Martin Luther King employed with great effect in the cause of human rights. This methodology is lost when human rights are unmoored from its history. Gilroy refers to this aspect as “sentimentality”. The language of human rights, at its most effective, speaks both to the human mind and to the human heart, as Martin Luther King did. Others well before him also use language of both heart and mind, as Paul Gilroy also notes:

[Angelina] Grimké elaborated upon this inspired refusal of the reduction of people to things in a memorable (1838) letter to her friend Catherine Beecher (the older sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe). …:

“The investigation of the rights of the slave has led me to better understanding of our own. I have found the Anti- slavery cause to be the high school of morals in our land—the school in which human rights are more fully investigated and better understood and taught, than in any other. Here a great fundamental principle is uplifted and illuminated, and from this central light rays innumerable stream all around. Human beings have rights, because they are moral beings: the rights of all men grown out of their moral nature, they have essentially the same rights. ”

Again, the exclusion of these aspects of human rights create a vacuum which is filled with an imagined reality lacking genuineness and disconnected from the human beings who struggled for human rights.

That imagined reality sometimes has the character of a dry and soulless legalism that reduces the great principles and values of human rights to mere rules to be forensically applied to determine a legal outcome. They implicitly substitute treaty rules and legal regulation for true humanity and a true spirit of “brotherhood”. As we saw, above, Martin Luther King, was well aware that human rights do not come from documents: “they are neither conferred by nor derive from the state“.

Gandhi perhaps captured this well when responding to a letter from UNESCO asking for input towards the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The substance of his reply is brief:

I’m afraid I can’t give you anything approaching your minimum. That I have no time for the effort is true enough. But what is truer is that I am a poor reader of literature past or present much as I should like to read some of its gems. Living a stormy life since my early youth, I had no leisure to do the necessary reading.

I learnt from my illiterate but wise mother that all rights to be deserved and preserved come from duty well done. Thus the very right to live accrues to us only when we do the duty of citizenship of the world. From this one fundamental statement, perhaps it is easy enough to define the duties of Man and Woman and correlate every right to some corresponding duty to be first performed. Every other right can be shown to be an usurpation hardly worth fighting for.”

Indirectly, Gandhi expresses a source of human rights which is far deeper than any documentary, or even philosophical source. He communicates a life of struggle that billions have faced over history, and continue to face today: a life in which there is no leisure to read. It is from these human beings that the universal cry for justice has echoed through history. He also expresses human rights in terms that anyone in the human rights movement will understand. Human rights are not achieved without taking up our duty to contributing to their realisation.

Eleanor Roosevelt put it this way on the tenth anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

“Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home – so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person; the neighbourhood he lives in; the school or college he attends; the factory, farm or office where he works. Such are the places where every man, woman and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination. Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere. Without concerned citizen action to uphold them close to home, we shall look in vain for progress in the larger world.”

There are numerous insights we can draw from the spiritual foundations of Martin Luther King’s work, irrespective of our own beliefs. Not only does each of us have human rights, we owe them to no human institution. We possess human rights “inherently” in our humanity. The struggle for a more just world is a shared struggle, and we have a right and obligation to stand for others human rights, just as much as our own. Human rights are as much a characteristic of the human heart as the human mind. As much as laws may assist in the realisation of human rights; they are an inadequate repository for them. Only the human heart is sufficiently expansive to contain them. The struggle for human rights requires faith in our ability as human beings to create a more just order. It requires us to draw on our inner ‘spiritual’ reserve. No matter how dark the immediate horizon may be; no matter how far the dawn; the day will come when the oppressions of today are no more.

There is something else. In a world that is in our own day so publicly secular and distrustful of the contribution that religion might make; something is surprising. We have largely forgotten how recently it was, that Christianity played a pivotal role in one of the key human rights struggles of history.

Martin Luther King and Non-violence

Martin Luther King thought deeply about the best methods to use to overcome the injustices facing African Americans. This in itself is an important observation. It is appropriate for us in the 21st century to also think deeply about questions of method.

His speeches frequently describe and defend nonviolence as the method he felt was both effective and moral for the issues on which he worked. Sometimes the description was in response to criticism of the method as “too extreme”, at other times it was to reject the violence advocated by some.

His explanations were patient and detailed.

The basic steps of the method are outlined to his fellow ministers in his letter from a Birmingham jail.

“In any nonviolent campaign there are four basic steps: collection of the facts to determine whether injustices exist; negotiation; self-purification; and direct action. We have gone through all these steps in Birmingham.”

In his American dream speech, he identifies three characteristics of the method: its effectiveness, its moral grounding and its characteristic of love.

“First I should say that I am still convinced that the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom and human dignity is nonviolent resistance. I am convinced that this is a powerful method. It disarms the opponent, it exposes his moral defences, it weakens his morale and at the same time it works on his conscience, and he just doesn’t know how to deal with it. … If he beats you, you develop the courage of accepting blows without retaliating .. if he puts you in jail, you go in that jail and transform it from a dungeon of shame to a haven of freedom and human dignity … “

He thus saw it as an effective approach. He also saw it as a moral approach.

“[nonviolence] makes it possible for individuals to struggle to secure moral ends through moral means. … because in a real sense the end is pre-existent in the means. And the means represent the ideal in the making and the end in the process.”

As to love he explains:

“It says it is possible to struggle passionately and unrelentingly against an unjust system and yet not stoop to hatred in the process. The love ethic can stand at the centre of a nonviolent movement”.

He draws on his training in classical Greek which has three kinds of love to explain how it is possible, not to like, but to love an oppressor. He is not speaking of “eros” (aesthetic or romantic love) or “philia” (love grounded in friendship). Rather he means “agape”.

“Agape is understanding, creative redemptive good will for all men. It is an overflowing love that seeks nothing in return. Theologians would say that it is the love of God operating in the human heart. And when one rises to love on this level, he loves every man, not because he likes him but because God loves him. And he rises to the level of loving the person who does the evil deed while hating the deed that the person does. And this I think is the kind of love that can guide us through the days and weeks and years ahead. This is the kind of love that can help us achieve and create the beloved community”

These three underlying rationales of the method can be applied to consider questions of human rights methodology in a 21st century context.

A further dimension of the nonviolent approach taught by Martin Luther King was the inspiration derived from Gandhi’s nonviolent movement for self-determination against British colonialism. In his American Dream speech Martin Luther King says “We will meet your physical force with soul force.” In the Gandhian original ‘soul force’ is ‘satyagraha’. In his speech on accepting the Nobel Peace Prize, Martin Luther King states explicitly the source of the nonviolent method:

“Negroes of the United States, following the people of India, have demonstrated that nonviolence is not sterile passivity, but a powerful moral for which makes for moral transformation.”

In his 1959 article “My trip to the land of Gandhi” he expands further:

“While the Montgomery boycott was going on, India’s Gandhi was the guiding light of our technique of non-violent social change. We spoke of him often. … I was delighted that the Gandhians accepted us with open arms. They praised our experiment with the non-violent resistance technique at Montgomery. They seem to look upon it as an outstanding example of the possibilities of its use in western civilization.”

What is striking about the Gandhian connection is that although drawing from completely different philosophical traditions, people facing oppressions a world apart, discovered common principles, values and methods for the attainment of human rights. This is universality.

It is clear that Martin Luther King saw nonviolence as a method of addressing oppression and violence that is worthy of human dignity.

“… nonviolence is the answer to the crucial political and moral question of our time – the need for man to overcome oppression and violence without resorting to violence and oppression. Civilization and violence are antithetical concepts. … man must evolve for all human conflict a method which rejects revenge, aggression and retaliation. The foundation of such a method is love.”

Although proven to be more effective and of course more moral than violent methods, nonviolent methods of overcoming oppression have been attempted in recent decades with mixed results. In Eastern Europe they were often successful in ending totalitarian regimes and establishing inclusive governance that better served the needs of the people. The Philippines offers another example of effective nonviolent change.

In a number of cases attempts at nonviolent change were followed by an outbreak of violence that dragged society into profoundly worse conditions. Recent examples include Libya, Syria and Egypt, and conflicts in Eastern Europe.

Sometimes nonviolence was met with a violence that rendered the method futile. In the cases of Burma and China nonviolent protests were violently suppressed, although Burma ultimately moved towards democratic change.

Thus, nonviolence is not always effective. The factors that came together for success in the U.S. civil right movement, are not always present.

Finally in the early 21st century violence, even by a handful of individuals, has the power to destroy thousands of human lives, or to polarize and destabilize entire countries.

A question that we must seriously consider in the context of the increasingly easy and obscene resort to violence in the 21st century, is: are there even better methods than nonviolence? That is, are there methods which do not carry the risk of provoking violent responses, or the risk of contributing to a polarisation which leads to civil conflict, or the risk of empowering new violence prone oppressors?

In the South African case, the end of apartheid seems to have been at least in part mediated by a process of negotiation and pursuit of shared goals by community leaders on both sides of the racial divide. In that case, the heirs of an unjust system were active participants in its dismantlement. This was of course also true of the civil rights reforms in the United States, which depended on support from federal authorities.

It may be observed that the nonviolent method can be seen as a dramatisation. It casts the people and communities involved in archetypal “evil” and “good” roles. For example, these words of Martin Luther King illuminate the method:

Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored. …

Like a boil that can never be cured so long as it is covered up but must be opened with an its ugliness to the natural medicines of air and light, injustice must be exposed, with all the tension its exposure creates, to the light of human conscience and the air of national opinion before it can be cured.

While effective in its historical context, the method is necessarily polarising and therefore inherently risk prone. An aspect of Martin Luther King’s approach that perhaps was critical in achieving a successful outcome, was that his approach was not limited to making visible the evil of segregation; he also made visible a vision of a more enlightened community – ‘the dream’ – of which he often speaks. He led people towards that dream, as much as away from racism and segregation.

Such armchair observations, are easy for those of us who are beneficiaries of the current state of affairs. That is likely exactly what Martin Luther King would say. Whatever view we may have of nonviolence as a method, no action at all in the face of injustice is an abnegation of responsibility. The needs of justice, for those who are victims of injustice, are an immediate reality. They cannot be put off to a future time when the beneficiaries of a current order may be cajoled towards a more just state of affairs. Martin Luther King makes this point in phrases such as: “We are confronted with the fierce urgency of now … there is such a thing as being too late.”

In an oppressive situation there are at least two communities affected by oppression: those who are suffering and are its victims; and those who perpetrate oppression, or just as bad those who are the beneficiaries of oppression and do nothing to address it. Those who are oppressed, in a real sense, are not “the problem”. It is those who are beneficiaries of injustice and find it acceptable who have “the problem”.

Sometimes it is the beneficiaries of oppression who mobilize against it. A leading example is the struggle for abolition of the slave trade in the United Kingdom. There, members of UK society itself, were those who led the struggle against slavery. Although they did not themselves experience oppression, they recognised their responsibility to be part of the process of bringing it to an end. An examplar, is the voice of Thomas Clarkson, who as a young graduate of Cambridge University decided to dedicate himself to the struggle against slavery.

… the subject of [the slave trade] almost wholly engrossed my thoughts. I became at times very seriously affected while upon the road. I stopped my horse occasionally, and dismounted and walked. I frequently tried to persuade myself in these intervals that the contents of my Essay [on the slave trade] could not be true. The more however I reflected upon them, or rather upon the authorities on which they were founded, the more I gave them credit. Coming in sight of Wades Mill in Hertfordshire, I sat down disconsolate on the turf by the roadside and held my horse. Here a thought came into my mind, that if the contents of the Essay were true, it was time some person should see these calamities to their end. Agitated in this manner I reached home.

What are the best methods for addressing the injustices and maladies of the 21st century? There is no easy answer to this question. There are other movements that perhaps provide insights: the women’s movement (for which no single bullet was ever fired); and the peace movement. Are even more profoundly pacific methods or more nuanced nonviolent methods: perhaps something akin to non-adversarialism, needed today? Martin Luther King, who thought long and carefully about questions of method certainly teaches us that such thought is required if human rights are to be successfully pursued in a manner worthy of human dignity. We should at least aspire to no less enlightened methods than the ones he pursued. And to all those who use or justify violence in our century in the name of “justice”, Martin Luther King’s words and actions say clearly: “you are wrong”. If violence is not necessary to overcome 340 years of oppression; it is not necessary to any cause.

Something else that Martin Luther King observes in relation to nonviolence remains an important contribution of his thought – that the method of nonviolence transcends sectional interests and rejects the substitution of future tyrannies:

Martin Luther King, Peace and World Brotherhood

To fully appreciate Martin Luther King’s thoughts on peace, we must understand his thoughts about the relationship between human beings.

He saw all human beings as caught “in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.” He expands on this thought in his 1964 speech, “The American Dream”.

All I’m saying is simply this, that all life is interrelated. And we are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny — whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. For some strange reason I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be, and you can never be what you ought to be until I am what I ought to be. This is the interrelated structure of reality. … I think this is the first challenge and it is necessary to meet it in order to move on toward the realization of the American Dream, the dream of men of all races, creeds, national backgrounds, living together as brothers.

In this context he recasts the American Dream as a universal dream.

I would like to start on the world scale, so to speak, by saying if the American Dream is to be a reality we must develop a world perspective. It goes without saying that

the world in which we live is geographically one, and now more than ever before we are challenged to make it one in terms of brotherhood. … through our scientific genius we have made of this world a neighborhood, and now through our moral and ethical commitment, we must make of it a brotherhood. We must all learn to live together as brothers or we will all perish together as fools. This is the challenge of the hour. No individual can live alone, no nation can live alone. Somehow we are interdependent.

The implications of these insights on the nature of human relationships lead to his advocacy of peace in the context of the Vietnam War.

In April 1967 in a speech titled “Beyond Vietnam”, he outlined the reasons why he felt he had to speak out on the war in Vietnam.

“Over the past two years, as I have moved to break the betrayal of my own silences and to speak from the burnings of my own heart, as I have called for radical departures from destruction of Vietnam, many persons have questioned me about the wisdom of my path.”

He offered seven reasons for his opposition.

First was the adverse impact of warfare on his efforts to alleviate poverty of African-Americans.

There is at the outset a very obvious and almost facile connection between the war in Vietnam and the struggle I and others have been waging in America. A few years ago there was a shining moment in that struggle. It seemed as if there was a real promise of hope for the poor, both black and white, through the poverty program. … Then came the buildup in Vietnam, and I watched this program broken and eviscerated as if it were some idle political plaything on a society gone mad on war. And I knew that America would never invest the necessary funds or energies in rehabilitation of its poor so long as adventures like Vietnam continued … So I was increasingly compelled to see the war as an enemy of the poor and to attack it as such.

Second was the direct harm of the war on the lives of African American young men and families.

it became clear to me that the war was doing far more than devastating the hopes of the poor at home. It was sending their sons and their brothers and their husbands to fight and to die in extraordinarily high proportions … We were taking the black young men … and sending them eight thousand miles away to guarantee liberties in Southeast Asia which they had not found in southwest Georgia and East Harlem. So we have been repeatedly faced with the cruel irony of watching Negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools.

Third was the need to speak against violence as a solution to problems.

As I have walked among the desperate, rejected, and angry young men, I have told them that Molotov cocktails and rifles would not solve their problems. … But they asked, and rightly so, “What about Vietnam?” They asked if our own nation wasn’t using massive doses of violence to solve its problems, … Their questions hit home, and I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today: my own government.

Fourth was the American Dream, that any solution must realise that dream in larger proportions.

In a way we were agreeing with Langston Hughes, that black bard from Harlem, who had written earlier:

O, yes, I say it plain,

America never was America to me,

And yet I swear this oath—

America will be!Now it should be incandescently clear that no one who has any concern for the integrity and life of America today can ignore the present war. … America’s soul … can never be saved so long as it destroys the hopes of men the world over. So it is that those of us who are yet determined that “America will be” are led down the path of protest and dissent, working for the health of our land.

Sixth, he cites his commitment as a Christian minister, in addition to the charge laid on him by the Nobel Peace Prize.

To me, the relationship of this ministry to the making of peace is so obvious that I sometimes marvel at those who ask me why I am speaking against the war. … Have they forgotten that my ministry is in obedience to the one who loved his enemies so fully that he died for them?

Finally, he cites the oneness of humanity, the theme of “brotherhood”.

Beyond the calling of race or nation or creed is this vocation of sonship and brotherhood. Because I believe that the Father is deeply concerned, especially for His suffering and helpless and outcast children, I come tonight to speak for them. This I believe to be the privilege and the burden of all of us who deem ourselves bound by allegiances and loyalties which are broader and deeper than nationalism and which go beyond our nation’s self-defined goals and positions. We are called to speak for the weak, for the voiceless, for the victims of our nation, for those it calls “enemy,” for no document from human hands can make these humans any less our brothers.

Here his words, in respect of how we view our fellow human beings, recall words he wrote to his fellow Ministers from his prison cell in Birmingham.

Segregation, to use the terminology of the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber, substitutes an “I-it” relationship for an “I-thou” relationship and ends up relegating persons to the status of things.

Later in his speech he turns to the question of values, calling for a “revolution of values”.

I am convinced … we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights, are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.

He continues on poverty:

A true revolution of values will soon look uneasily on the glaring contrast of poverty and wealth.

On war:

A true revolution of values will lay hand on the world order and say of war, “This way of settling differences is not just.”

War is not the answer.

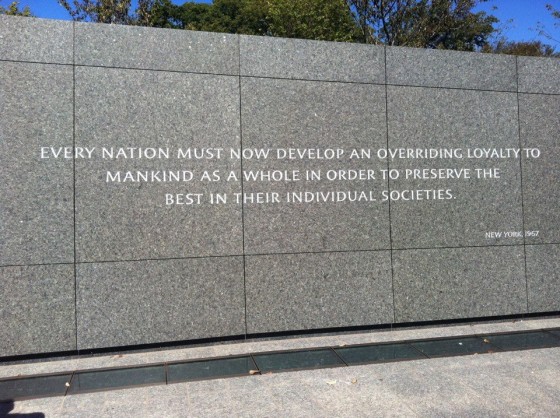

Finally, the capstone of the revolution in values for which he calls is an expansion of loyalties from the particular to the universal:

A genuine revolution of values means in the final analysis that our loyalties must become ecumenical rather than sectional. Every nation must now develop an overriding loyalty to mankind as a whole in order to preserve the best in their individual societies.

It is a re-orientation to humanity as a whole as the highest value. It is not however a vague “emotional bosh” he means:

This call for a worldwide fellowship that lifts neighborly concern beyond one’s tribe, race, class, and nation is in reality a call for an all-embracing and unconditional love for all mankind. This oft misunderstood, this oft misinterpreted concept, … has now become an absolute necessity for the survival of man. When I speak of love I am not speaking of some sentimental and weak response. I’m not speaking of that force which is just emotional bosh. I am speaking of that force which all of the great religions have seen as the supreme unifying principle of life. … We can no longer afford to worship the god of hate or bow before the altar of retaliation. The oceans of history are made turbulent by the ever-rising tides of hate.

It is impossible to separate Martin Luther King’s advocacy of peace from the other aspects of his thought, they are part of the same cloth, understood from different perspectives. In his views on war, he still speaks primarily to the same audience: the “oppressed” who have come on the journey of civil rights, but the audience is now re-conceptualised as the “privileged”, members of a society benefiting from wider global inequities. Here he thus speaks with the same self-critical voice that the earlier abolitionists of the slave trade spoke.

When we consider his words, we see that they are far more than rhetoric. They communicate the insights of a complex world-view. We see that his words have considerable courage. Of course, to oppose segregation itself took great courage. To speak out against the Vietnam War, when he did, was an act of courage. To speak out for a wider loyalty to humanity as a whole was an act of courage. It is evident that he saw these stances as necessary for the welfare of those he served, and the dispossessed in the world as a whole.

As a human rights advocate he spoke for peace in a time of war. Almost half a century later the world remains beset by wars. The same concerns of the adverse impacts of war on the attainment of human rights in his time, remain pertinent. It is moreover hardly possible to separate the cause of peace from the cause of human rights. They are in reality, one and the same cause. For human rights workers, peace is a necessary precondition of progress in human rights. When fear and war seizes the public mind, human rights are stalled for years or decades and often hard won principles are torn to shreds. In the case of the abolition of the slave trade, the Napoleonic Wars delayed abolition for 20 years. In conditions of war human rights cannot progress. Appallingly, in the 21st century, while borders, barbed wire and walls, are erected with ever greater efficiency between people, the boundaries between war and peace have virtually broken down. This represents an existential threat to human rights.

Finally, few seem to appreciate the importance of what Martin Luther King communicated when he spoke of “wider loyalties”, the deeper “dream”, the journey which is still incomplete. For reasons which are mystifying, the establishment of a world society based on ‘love – agape’ between human beings, are rarely considered a ‘serious’ contribution to public policy.

Few advocate for the “revolution in values” which Martin Luther King espoused. It is difficult to find those who take the brother and sisterhood of humankind seriously in our halls of learning. Regretfully. Rarely do the words of our political leaders rise to such a noble orientation worthy of human dignity. Sadly. Even in the advocacy of those who stand for and devote their lives to human rights, often the theme of ‘brother/sisterhood’ falls far behind in a race in which equality and freedom are out in front, and brother/sisterhood almost forgotten.

If human rights is to achieve its purpose in the world, this third theme of human rights must be recaptured. If Martin Luther King is right, it must be brought to the centre of human rights advocacy, with all that implies.