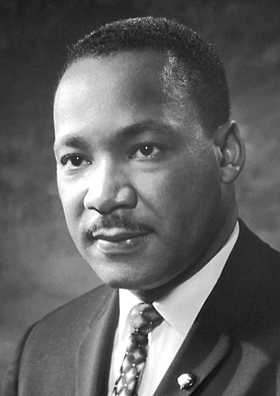

Martin Luther King and Non-violence (Part 3 of 4)

Martin Luther King thought deeply about the best methods to use to overcome the injustices facing African Americans. This in itself is an important observation. It is appropriate for us in the 21st century to also think deeply about questions of method.

His speeches frequently describe and defend nonviolence as the method he felt was both effective and moral for the issues on which he worked. Sometimes the description was in response to criticism of the method as “too extreme”, at other times it was to reject the violence advocated by some.

His explanations were patient and detailed.

The basic steps of the method are outlined to his fellow ministers in his letter from a Birmingham jail.

“In any nonviolent campaign there are four basic steps: collection of the facts to determine whether injustices exist; negotiation; self-purification; and direct action. We have gone through all these steps in Birmingham.”

In his American dream speech he identifies three characteristics of the method: its effectiveness, its moral grounding and its characteristic of love.

“First I should say that I am still convinced that the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom and human dignity is nonviolent resistance. I am convinced that this is a powerful method. It disarms the opponent, it exposes his moral defences, it weakens his morale and at the same time it works on his conscience, and he just doesn’t know how to deal with it. … If he beats you, you develop the courage of accepting blows without retaliating .. if he puts you in jail, you go in that jail and transform it from a dungeon of shame to a haven of freedom and human dignity … “

He thus saw it as an effective approach. He also saw it as a moral approach.

“[nonviolence] makes it possible for individuals to struggle to secure moral ends through moral means. … because in a real sense the end is pre-existent in the means. And the means represent the ideal in the making and the end in the process.”

As to love he explains:

“It says it is possible to struggle passionately and unrelentingly against an unjust system and yet not stoop to hatred in the process. The love ethic can stand at the centre of a nonviolent movement”.

He draws on his training in classical Greek which has three kinds of love to explain how it is possible, not to like, but to love an oppressor. He is not speaking of “eros” (aesthetic or romantic love) or “philia” (love grounded in friendship). Rather he means “agape”.

“Agape is understanding, creative redemptive good will for all men. It is an overflowing love that seeks nothing in return. Theologians would say that it is the love of God operating in the human heart. And when one rises to love on this level, he loves every man, not because he likes him but because God loves him. And he rises to the level of loving the person who does the evil deed while hating the deed that the person does. And this I think is the kind of love that can guide us through the days and weeks and years ahead. This is the kind of love that can help us achieve and create the beloved community”

These three underlying rationales of the method can be applied to consider questions of human rights methodology in a 21st century context.

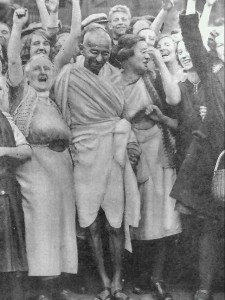

A further dimension of the nonviolent approach taught by Martin Luther King was the inspiration derived from Gandhi’s nonviolent movement for self-determination against British colonialism. In his American Dream speech Martin Luther King says “We will meet your physical force with soul force.” In the Gandhian original ‘soul force’ is ‘satyagraha’. In his speech on accepting the Nobel Peace Prize, Martin Luther King states explicitly the source of the nonviolent method:

“Negroes of the United States, following the people of India, have demonstrated that nonviolence is not sterile passivity, but a powerful moral for which makes for moral transformation.”

In his 1959 article “My trip to the land of Gandhi” he expands further:

What is striking about the Gandhian connection is that although drawing from completely different philosophical traditions, people facing oppressions a world apart, discovered common principles, values and methods for the attainment of human rights. This is universality.

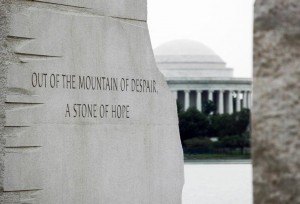

It is clear that Martin Luther King saw nonviolence as a method of addressing oppression and violence that is worthy of human dignity.

“… nonviolence is the answer to the crucial political and moral question of our time – the need for man to overcome oppression and violence without resorting to violence and oppression. Civilization and violence are antithetical concepts. … man must evolve for all human conflict a method which rejects revenge, aggression and retaliation. The foundation of such a method is love.”

Although proven to be more effective and of course more moral than violent methods, nonviolent methods of overcoming oppression have been attempted in recent decades with mixed results. In Eastern Europe they were often successful in ending totalitarian regimes and establishing inclusive governance that better served the needs of the people. The Philippines offers another example of effective nonviolent change.

In a number of cases attempts at nonviolent change were followed by an outbreak of violence that dragged society into profoundly worse conditions. Recent examples include Libya, Syria and Egypt, and conflicts in Eastern Europe.

Sometimes nonviolence was met with a violence that rendered the method futile. In the cases of Burma and China nonviolent protests were violently suppressed, although Burma ultimately moved towards democratic change.

Thus nonviolence is not always effective. The factors that came together for success in the U.S. civil right movement, are not always present.

Finally in the early 21st century violence, even by a handful of individuals, has the power to destroy thousands of human lives, or to polarize and destabilize entire countries.

A question that we must seriously consider in the context of the increasingly easy and obscene resort to violence in the 21st century, is: are there even better methods than nonviolence? That is, are there methods which do not carry the risk of provoking violent responses, or the risk of contributing to a polarisation which leads to civil conflict, or the risk of empowering new violence prone oppressors?

In the South African case, the end of apartheid seems to have been at least in part mediated by a process of negotiation and pursuit of shared goals by community leaders on both sides of the racial divide. In that case, the heirs of an unjust system were active participants in its dismantlement. This was of course also true of the civil rights reforms in the United States, which depended on support from federal authorities.

It may be observed that the nonviolent method can be seen as a dramatisation. It casts the people and communities involved in archetypal “evil” and “good” roles. For example these words of Martin Luther King illuminate the method:

Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored. …

Like a boil that can never be cured so long as it is covered up but must be opened with an its ugliness to the natural medicines of air and light, injustice must be exposed, with all the tension its exposure creates, to the light of human conscience and the air of national opinion before it can be cured.

While effective in its historical context, the method is necessarily polarising and therefore inherently risk prone. An aspect of Martin Luther King’s approach that perhaps was critical in achieving a successful outcome, was that his approach was not limited to making visible the evil of segregation; he also made visible a vision of a more enlightened community – ‘the dream’ – of which he often speaks. He led people towards that dream, as much as away from racism and segregation.

Such armchair observations, are easy for those of us who are beneficiaries of the current state of affairs. That is likely exactly what Martin Luther King would say. Whatever view we may have of nonviolence as a method, no action at all in the face of injustice is an abnegation of responsibility. The needs of justice, for those who are victims of injustice, are an immediate reality. They cannot be put off to a future time when the beneficiaries of a current order may be cajoled towards a more just state of affairs. Martin Luther King makes this point in phrases such as: “We are confronted with the fierce urgency of now … there is such a thing as being too late.”

In an oppressive situation there are at least two communities affected by oppression: those who are suffering and are its victims; and those who perpetrate oppression, or just as bad those who are the beneficiaries of oppression and do nothing to address it. Those who are oppressed, in a real sense, are not “the problem”. It is those who are beneficiaries of injustice and find it acceptable who have “the problem”.

Sometimes it is the beneficiaries of oppression who mobilize against it. A leading example is the struggle for abolition of the slave trade in the United Kingdom. There, members of UK society itself, were those who led the struggle against slavery. Although they did not themselves experience oppression, they recognised their responsibility to be part of the process of bringing it to an end. An examplar, is the voice of Thomas Clarkson, who as a young graduate of Cambridge University decided to dedicate himself to the struggle against slavery.

… the subject of [the slave trade] almost wholly engrossed my thoughts. I became at times very seriously affected while upon the road. I stopped my horse occasionally, and dismounted and walked. I frequently tried to persuade myself in these intervals that the contents of my Essay [on the slave trade] could not be true. The more however I reflected upon them, or rather upon the authorities on which they were founded, the more I gave them credit. Coming in sight of Wades Mill in Hertfordshire, I sat down disconsolate on the turf by the roadside and held my horse. Here a thought came into my mind, that if the contents of the Essay were true, it was time some person should see these calamities to their end. Agitated in this manner I reached home.

What are the best methods for addressing the injustices and maladies of the 21st century? There is no easy answer to this question. There are other movements that perhaps provide insights: the women’s movement (for which no single bullet was ever fired); and the peace movement. Are even more profoundly pacific methods or more nuanced nonviolent methods: perhaps something akin to non-adversarialism, needed today? Martin Luther King, who thought long and carefully about questions of method certainly teaches us that such thought is required if human rights are to be successfully pursued in a manner worthy of human dignity. We should at least aspire to no less enlightened methods than the ones he pursued. And to all those who use or justify violence in our century in the name of “justice”, Martin Luther King’s words and actions say clearly: “you are wrong”. If violence is not necessary to overcome 340 years of oppression; it is not necessary to any cause.

Something else that Martin Luther King observes in relation to nonviolence remains an important contribution of his thought – that the method of nonviolence transcends sectional interests and rejects the substitution of future tyrannies:

And he will realize that a doctrine of black supremacy is as dangerous as a doctrine of white supremacy, and that God is not interested merely in the freedom of black men, and brown men, and yellow men; but God is interested in the freedom of the whole human race and the creation of a society where all men will live together as brothers, and every man will respect the dignity and worth of human personality. This is what the nonviolent discipline, when one takes it seriously, says.