Martin Luther King Civil Rights Leader and Peace Advocate (Part 1 of 4)

Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his life for the poor of the world, the garbage workers of Memphis and the peasants of Vietnam. The day that Negro people and others in bondage are truly free, on the day want is abolished, on the day wars are no more, on that day I know my husband will rest in a long-deserved peace.

—Coretta King

This article is part of a series on human rights forebears. Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr lived a life beyond the ordinary and writing about him is challenging. His life made the world that came after him better. This article will not do justice to his contribution. Nonetheless, as with previous articles, the aim is to learn what Martin Luther King teaches us for the human rights issues of today. The focus of this article will be on Martin Luther King’s thought, mainly as expressed in his recorded speeches, rather than on the civil rights movement as a whole.

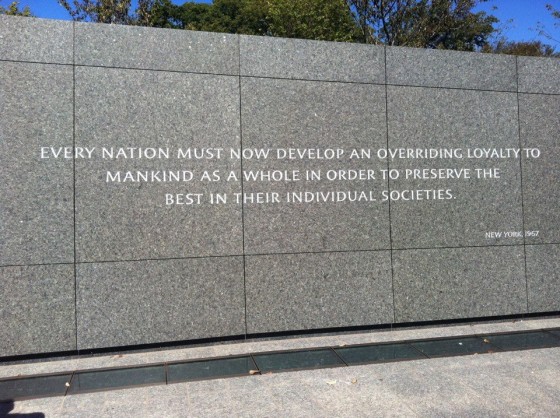

In popular media, Martin Luther King is projected almost solely as a leader of the civil rights movement. This of course he was, and it was central to his work. But the picture is incomplete. Other aspects of his thought include the spiritual reservoir from which he drew; his advocacy of nonviolent methods; his profound belief in the interconnectedness of all human beings and his advocacy of peace.

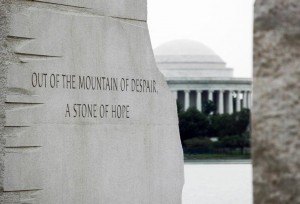

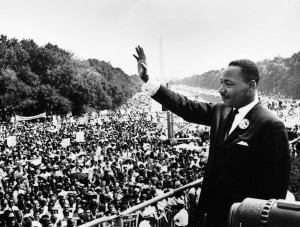

He is a figure who stands at the birth of the world in which we now live. His life and work marked a watershed. In our world, racism is a condemned ideology. We are so used to this reality that we may unconsciously project our realities back to the world as it was in his time. Over and over we hear Martin Luther King’s words echoed in our popular media: “I have a dream“. We enjoy the benefits of the translation of Martin Luther King’s dream into reality. As a civil rights leader, he worked for, and gave his life to end racial segregation and racism in the United States. His work was part of a global trend which has rejected the ideology of racism. While racism still exists in the world, while it is still virulent and hateful, it is an ideology of the past, not the future.

Martin Luther King’s human rights work was deeply motivated by what he drew from his personal history and commitment as a Christian leader. This source can be seen in how he conceived of the struggle to contribute to a more just world, and as a spiritual reservoir which gave strength and resilience to his work. His adoption of the methods of nonviolence to pursue civil rights goals is an important aspect of what he did. A further aspect of his life that attracts less attention than it ought, is his advocacy of peace. This is one of the main pieces of unfinished work which he left us. While we may be tempted to think of these dimensions as separate, it is likely that for him, they were part of one integral whole. All of these aspects belong together. For example, his advocacy for peace built on his advocacy for human rights, and he explained it, as a necessary extension of the work he did in the civil rights movement.

Martin Luther King lived from 1928 until his assassination on 4 April 1968. His death, along with the killings of John and Robert Kennedy in the space of a few years brought to an end an era of visionary progressive leadership in the United States.

Before looking further at his life and thought, a review of the changes associated with the Civil Rights Movement, give a sense of the scope of the transformation to which Martin Luther King contributed. The following are pieces of legislation designed to address the injustices that were among the fruits of the civil rights movement.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, colour or national origin in employment and public accommodation. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 protected the right of all citizens to vote. The Immigration and Nationality Services Act of 1965 opened immigration to the United States to non-Europeans and the Fair Housing Act of 1965 banned discrimination in the sale and rental of private housing.

Each item of legislation addressed a real and deep field of injustice, most that were particularly experienced by African Americans. Martin Luther King’s words capture some of these profound denials, in ways that such a list can never capture.

Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, “Wait.” But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate filled policemen curse, kick and even kill your black brothers and sisters; when you see the vast majority of your twenty million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society; when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six year old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky, and see her beginning to distort her personality by developing an unconscious bitterness toward white people; when you have to concoct an answer for a five year old son who is asking: “Daddy, why do white people treat colored people so mean?”; when you take a cross county drive and find it necessary to sleep night after night in the uncomfortable corners of your automobile because no motel will accept you; when you are humiliated day in and day out by nagging signs reading “white” and “colored”; when your first name becomes “nigger,” your middle name becomes “boy” (however old you are) and your last name becomes “John,” and your wife and mother are never given the respected title “Mrs.”; when you are harried by day and haunted by night by the fact that you are a Negro, living constantly at tiptoe stance, never quite knowing what to expect next, and are plagued with inner fears and outer resentments; when you are forever fighting a degenerating sense of “nobodiness”–then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait.

The oppression the civil rights movement addressed was as pervasive and profound as any in human history.

As a civil rights leader, Martin Luther’s achievement is of course captured in his “I have a dream” speech of 28 August 1968. It is so well-known that it hardly needs repetition. As a speaker he was masterful, but that mastery was not only in respect of words, it was in respect of ideas. He framed the civil rights movement as a universal movement for the fulfilment of the accepted but unrealised values of the society to which he belonged. In doing so he enabled those around him to see and conceive of the civil rights movement not as an African-American movement solely concerned with African-American rights – but rather a universal movement concerned with the realisation of deeply shared human values and aspirations. In its fullest sense his vision of justice included all human beings.

Part 2, released tomorrow, will look at the role Christianity played in Martin Luther King’s human rights work. Part 3 will explore Martin Luther King’s use of nonviolence as a vehicle for social change. Part 4 is on Martin Luther King as a peace advocate.