Martin Luther King Jr. – What role did Christianity play in his civil rights advocacy? (Part 2 of 4)

Martin Luther King Jr. was born in Atlanta Georgia, the second son of Martin Luther King Sr. and Alberta Williams King.

Martin Luther King Jr. was by vocation a Baptist minister. He was in the fourth generation of his family to take up this vocation. It is impossible to fully appreciate Martin Luther King’s work without understanding the role that Christian thought and inspiration played in his advocacy of human rights.

Martin Luther King’s letter from a Birmingham prison to fellow Christian clergymen gives insight to the role his religious commitment played in generating and sustaining his commitment to work for justice. Further, the people from whom he came, the African Americans who struggled against centuries of slavery and racism, drew from deep spiritual and human reservoirs in the long and bitter journey from slavery, through oppression and segregation, before the civil rights reforms were won.

In setting out why he was in Birmingham he explicitly drew on a ‘prophetic role’.

“I am in Birmingham because injustice is here. Just as the prophets of the eight century B.C. left their villages and carried their “thus saith the Lord” far beyond the boundaries of their home towns … so I am compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my home town.”

In explaining the nonviolent methods he practised, criticism of which he was responding to, he wrote:

“We have waited more than 340 years for our constitutional and God-given rights.”

He drew on biblical precedents for civil disobedience to the law, “on the ground that a higher moral law was at stake“. Human rights, as he conceived them, do not depend on the decision of any human agency. As a consequence, they can never be overridden by any human decision. It is a perspective which in the final analysis places human rights beyond the reach of any tyrant, no matter how powerful, and beyond the reach of any rationalisation offered by the powerful that claims a justification for the oppression of human beings.

In thinking about Martin Luther King’s Christianity, we would again miss something significant to his human rights advocacy if we didn’t consider how his spiritual practice was engaged in that work. The role that prayer played in Martin Luther King’s work, is captured in a recollection from his wife Coretta King.

Prayer was a wellspring of strength and inspiration during the Civil Rights Movement. Throughout the movement, we prayed for greater human understanding. We prayed for the safety of our compatriots in the freedom struggle. We prayed for victory in our nonviolent protests, for brotherhood and sisterhood among people of all races, for reconciliation and the fulfillment of the Beloved Community.

For my husband, Martin Luther King, Jr. prayer was a daily source of courage and strength that gave him the ability to carry on in even the darkest hours of our struggle.

I remember one very difficult day when he came home bone-weary from the stress that came with his leadership of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. In the middle of that night, he was awakened by a threatening and abusive phone call, one of many we received throughout the movement. On this particular occasion, however, Martin had had enough.

After the call, he got up from bed and made himself some coffee. He began to worry about his family, and all of the burdens that came with our movement weighed heavily on his soul. With his head in his hands, Martin bowed over the kitchen table and prayed aloud to God: “Lord, I am taking a stand for what I believe is right. The people are looking to me for leadership, and if I stand before them without strength and courage, they will falter. I am at the end of my powers. I have nothing left. I have nothing left. I have come to the point where I can’t face it alone.”

Later he told me, “At that moment, I experienced the presence of the Divine as I had never experienced Him before. It seemed as though I could hear a voice saying: ‘Stand up for righteousness; stand up for truth; and God will be at our side forever.'” When Martin stood up from the table, he was imbued with a new sense of confidence, and he was ready to face anything. (Coretta King – Standing in the Need of Prayer)

If one happens not to share Martin Luther King’s faith, what meaning can be drawn from what is described here? Within the act of prayer, part of what is described is Martin Luther King’s search for and discovery of knowledge in a time of deep uncertainty.

Another article considers the semi-autobiographical work, The Strange Alchemy of Life and Law by, Justice Albie Sachs. From South Africa, much of Justice Sach’s life has also been devoted to human rights through the struggle against apartheid, as well as to law. Justice Sachs describes himself as Jewish but non-religious: “not practising in any way”. Yet he states in his book: “I did in fact have a strong set of beliefs, my own world view, in many ways a deeply spiritual one with overwhelming ethical implications.” Speaking of solving problems in the law, he speaks about moments of inspiration as being the most creative and productive: “only when I had been close to being in what my Buddhist friends would call a transcendental meditational state, would these formulations emerge, as if from nowhere … it so happened that the first three times I was cited in foreign jurisdictions, the formulations had all come to me at moments when my brain had been least engaged in hard legal reasoning”. Looked at in ways that transcend mere words, there is much that is common in the human experience. The inner resources that Martin Luther King drew upon do not depend on how we choose to describe ourselves nor on the particular model of reality we may hold. They likely do depend on some form of engagement with our inner “spiritual” life; however we might describe it.

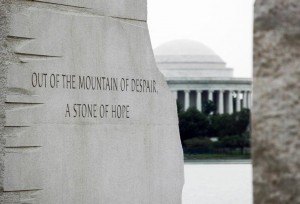

Most poignantly, the deep spirituality of Martin Luther King’s journey, is captured in the final words of the speech he delivered the evening before his murder. There were fears that evening. Threats had been made. He spoke of how happy he was to live in the time of the civil rights movement, having survived an earlier assassination attempt, and having seen the victories that had been won. How happy he was to have lived long enough to undertake the work he felt he had to do, and had now completed. In his last words he was a Moses to his people.

“Well, I don’t know what will happen to me now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t matter what happens to me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we, as a people will get to the promised land. And I’m happy tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

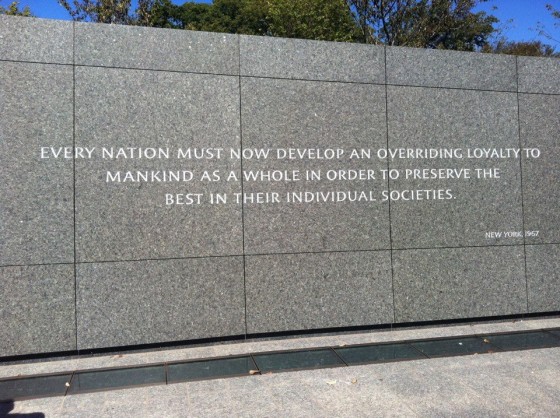

The spiritual roots of human rights on which he drew, are also seen in his speech titled “the American Dream”, delivered in 1964, where he spoke on the concept of rights, as found in the U.S. Declaration of Independence. He says of its well known opening phrases affirming the core values of human rights that, “This is a dream.” He means it is a dream that neither existed at the time the Declaration was originally written, nor did it exist in his own day. He identifies as distinctive of this dream that:

“It says that each individual has certain basic rights that are neither derived from nor conferred by the state. They are gifts from the hands of the Almighty God.”

In his speech in 1964 accepting the Nobel Peace Prize his words speak of the power of “faith”. In this case his words are not so much addressing “religious” faith, as addressing a “faith” that sustains the struggle against oppression, even in the direst circumstances.

“I refuse to accept the view that mankind is so tragically bound to the starless midnight of racism and war that the bright daybreak of peace and brotherhood can never become a reality. …

“I still believe that mankind will bow before the altars of God and be crowned triumphant over war and bloodshed … I still believe that we shall overcome.

“This faith can give us courage to face the uncertainties of the future. It will give our tired feet new strength as we continue our forward stride toward the city of freedom. When our days become dreary with low-hovering clouds and our nights become darker than a thousand midnights, we will known that we are living in the creative turmoil of a genuine civilization struggling to be born.”

These are the words of a man and a people whose faith have sustained them through centuries of oppression.

In international fora, and in the 21st century, human rights work is generally carried on without reference to any ‘higher authority’.

In part, this is a consequence of the need for universality – the necessity of adopting and speaking a language and concepts that are accessible for all human beings irrespective of historical background and irrespective of belief. Of using language that does not exclude the dreams of any human being for justice. Thus when, in 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights re-expressed “the dream”, it did not mention “God”. Not because faith was not important to a number of those involved in the creation of the Declaration, but because those involved felt this new language should be a wider dream inclusive of all human beings irrespective of “belief”.

Their insight was of course right.

However, a heavy price is paid if, from a justifiable concern for universality, we disconnect human rights from its genuine human history.

One price, is the unmooring of human rights from the lives of the human beings who gave us human rights. Many, as a matter of historical fact, were motivated by their religious beliefs. Many were not. But human rights cannot be understood if the actual stories of the human beings involved are not told and re-told. Each story gives us new insight. Where that story includes faith, it requires neither minimisation nor excuse. Rather the insights that they offer need to be gathered and contributed back into the flow of today’s and tomorrow’s human rights work. Without these human stories, the roots of human rights are stripped of their humanity. It was real human beings, with deep and complex motivations, who gave us human rights. By walking alongside them through their stories as they struggle to realise human rights, we learn what universality of human rights means far more deeply than from any philosophical argument.

Further if we do not tell the real history, other narratives are substituted that impoverish human rights history. Paul Gilroy in his oration Race and the Right to be Human has captured this well.

We meet this evening close to the 61st anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. As it became popular and influential, the political idea of human rights acquired a particular historical trajectory. The official genealogy it was given is extremely narrow. The story of its progressive development is usually told ritualistically as a kind of ethno-history. In that form, it contributes to a larger account of the moral and legal ascent of Europe and its civilizational offshoots.

The bloody histories of colonization and conquest are rarely allowed to disrupt that linear, triumphalist tale of cosmopolitan progress. Struggles against racial or ethnic hierarchy are not viewed as an important source or inspiration for human rights movements and ideologies. Advocacy on behalf of indigenous and subjugated peoples does not, for example, merit more than token discussion as a factor in shaping how the idea of universal human rights developed and what it could accomplish.

Needless to say, this substitute history is deeply inaccurate. In words that Martin Luther King might use, the “ought” of human rights and human aspiration is displaced and substituted by the “is” of the status quo. This status quo was, in Martin Luther King’s time, and remains in many ways in our own, profoundly unjust. To let an unjust present appropriate and clothe itself in human rights, places a high and unjustified barrier in the way further human rights progress. It disempowers those who like Martin Luther King, seek a better future than today.

Thirdly there is a specific methodology which human rights forebears like Martin Luther King employed with great effect in the cause of human rights. This methodology is lost when human rights are unmoored from its history. Gilroy refers to this aspect as “sentimentality”. The language of human rights, at its most effective, speaks both to the human mind and to the human heart, as Martin Luther King did. Others well before him also use language of both heart and mind, as Paul Gilroy also notes:

[Angelina] Grimké elaborated upon this inspired refusal of the reduction of people to things in a memorable (1838) letter to her friend Catherine Beecher (the older sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe). …:

“The investigation of the rights of the slave has led me to better understanding of our own. I have found the Anti- slavery cause to be the high school of morals in our land—the school in which human rights are more fully investigated and better understood and taught, than in any other. Here a great fundamental principle is uplifted and illuminated, and from this central light rays innumerable stream all around. Human beings have rights, because they are moral beings: the rights of all men grown out of their moral nature, they have essentially the same rights. ”

Again, the exclusion of these aspects of human rights create a vacuum which is filled with an imagined reality lacking genuineness and disconnected from the human beings who struggled for human rights.

That imagined reality sometimes has the character of a dry and soulless legalism that reduces the great principles and values of human rights to mere rules to be forensically applied to determine a legal outcome. They implicitly substitute treaty rules and legal regulation for true humanity and a true spirit of “brotherhood”. As we saw, above, Martin Luther King, was well aware that human rights do not come from documents: “they are neither conferred by nor derive from the state“.

Gandhi perhaps captured this well when responding to a letter from UNESCO asking for input towards the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The substance of his reply is brief:

I’m afraid I can’t give you anything approaching your minimum. That I have no time for the effort is true enough. But what is truer is that I am a poor reader of literature past or present much as I should like to read some of its gems. Living a stormy life since my early youth, I had no leisure to do the necessary reading.

I learnt from my illiterate but wise mother that all rights to be deserved and preserved come from duty well done. Thus the very right to live accrues to us only when we do the duty of citizenship of the world. From this one fundamental statement, perhaps it is easy enough to define the duties of Man and Woman and correlate every right to some corresponding duty to be first performed. Every other right can be shown to be an usurpation hardly worth fighting for.”

Indirectly, Gandhi expresses a source of human rights which is far deeper than any documentary, or even philosophical source. He communicates a life of struggle that billions have faced over history, and continue to face today: a life in which there is no leisure to read. It is from these human beings that the universal cry for justice has echoed through history. He also expresses human rights in terms that anyone in the human rights movement will understand. Human rights are not achieved without taking up our duty to contributing to their realisation.

Eleanor Roosevelt put it this way on the tenth anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

“Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home – so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person; the neighbourhood he lives in; the school or college he attends; the factory, farm or office where he works. Such are the places where every man, woman and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination. Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere. Without concerned citizen action to uphold them close to home, we shall look in vain for progress in the larger world.”

There are numerous insights we can draw from the spiritual foundations of Martin Luther King’s work, irrespective of our own beliefs. Not only does each of us have human rights, we owe them to no human institution. We possess human rights “inherently” in our humanity. The struggle for a more just world is a shared struggle and we have a right and obligation to stand for others human rights, just as much as our own. Human rights are as much a characteristic of the human heart as the human mind. As much as laws may assist in the realisation of human rights; they are an inadequate repository for them. Only the human heart is sufficiently expansive to contain them. The struggle for human rights requires faith in our ability as human beings to create a more just order. It requires us to draw on our inner ‘spiritual’ reserve. No matter how dark the immediate horizon may be; no matter how far the dawn; the day will come when the oppressions of today are no more.

There is something else. In a world that is in our own day so publicly secular and sometimes distrustful of the contribution that religion might make; something is surprising. We have largely forgotten how recently it was, that Christianity played a pivotal role in one of the key human rights struggles of history.

This article is the second part of four articles on Martin Luther King. Part 1 can be found here. Part 3, on nonviolence will be released tomorrow. Part 4 will look at Martin Luther King’s advocacy of peace.