Do Foreigners Have the Same Human Rights as the Rest of Us?

At the core of human rights is the axiomatic truth that human beings have inherent rights: that all human beings are equal and possessed of dignity and that violation of such rights is both morally offensive and legally impermissible. An alternative ordering of human relationships is mandated by exclusive national citizenship. Implicitly and explicitly national citizenship counsels the primacy of the privileged ‘citizen’ over the ‘non-citizen’ ‘other’. Everywhere we see the manifestation of this ordering in gross, systematic and widespread human rights violations: in our laws, practices, attitudes and media. Some of ‘us’ are the privileged beneficiaries of those violations: and we violate the human rights of foreigners as if it were the most natural thing in the world.

by Michael Curtotti and Emrys Nekvapil

- Introduction

- Returning to the roots of the human rights movement

- Bartolome de las Casas

- Some abolitionists

- Violation

- Equal in dignity and rights

- Freedom from discrimination

- Freedom of Movement

- Interdicting Movement

- Death

- Denial of Liberty / Mandatory detention

- Migrant workers

- Refugees: Queues and Warehouses

- The laws of oppression – US case

- Universal rights – universal citizenship

- Beyond the Border: Poverty and the Denial of Rights

- A work in progress

Introduction[1]

We live in a world which proclaims that all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights, that all are endowed with conscience and entitled without discrimination to certain fundamental human rights.

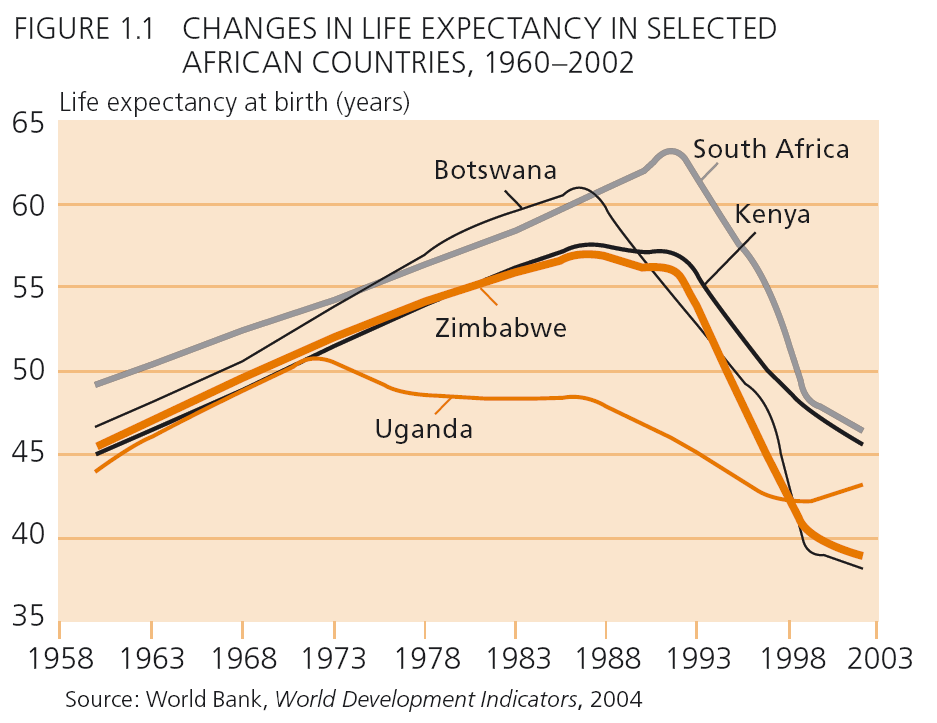

On the foundation of this idea an extensive edifice of laws, institutions and human endeavour has been built. Each of us is a beneficiary of this undeniable progress in human society. But we are beneficiaries unequally, for we also live in a world where 27 million people still live in slavery,[2] where 925 million are malnourished,[3] where genocide punctuates history, where racism still plagues our relationships and political systems, where women are denied human rights to some extent everywhere and profoundly in some places and where the benefits of historically unimaginable technologies are available to billions but effectively denied to equal numbers.

Parallel to, but even more powerfully than the legal and organisational structures of human rights, are the legal, administrative and military structures of the nation-state built upon and dedicated to the maintenance and promulgation of exclusive national citizenship and priority.

While these two structures have always been in tension, ‘foreignness’, and its abolition, is in the 21st century a pivotal human rights issue. By ‘foreignness’ we mean the treatment of our fellow human beings as ‘foreigners’: that is, violating their inherent human rights because they do not hold a citizenship status, or lesser right (such as residency), which we might recognise as entitling them to equal treatment. While human practises such as colonialism, slavery, segregation, gender discrimination and racism were the primary modalities of human oppression in previous centuries, in this century discrimination against non-citizens has displaced them as a primary justification on which hierarchies of privilege are constructed and in the name of which human rights violations are perpetrated.

The methods we seek to apply are those which come from the human rights movement. These methods teach us that insight is grounded in the experience of advocacy itself, leading, we hope, to action in the cause of human rights. While we could appeal to the words of the opening article of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as authority for such an approach and say that all human beings are endowed with ‘conscience’ and ‘should behave towards one another in the spirit of brotherhood’, to seek written authority would be to miss the point: for men and women have struggled in the cause of human rights long before they were embodied in clearly stated language. They did not need a written document such as the Universal Declaration to have ‘knowledge’ of the need to struggle for the realisation of human rights.

Looking to the history of the human rights movement – particularly the account of those who worked against colonialism, slavery and racism – brings inspiration. Yet human rights advocacy has always been about the possibility of an imagined future.

The future we imagine is one in which the human spirit has overcome the division between ‘foreigner’ and ‘native’ – where our national citizenship has no more moral or legal significance than our city of birth.

The full text of this paper can be read at: