The Universal Declaration of Human Rights: insights from its first draft

Until recent years it was hard to find good information on the origin of human rights. This was particularly true about the creation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration in 1998 began to change that picture as scholars began to turn their attention to the history of human rights.

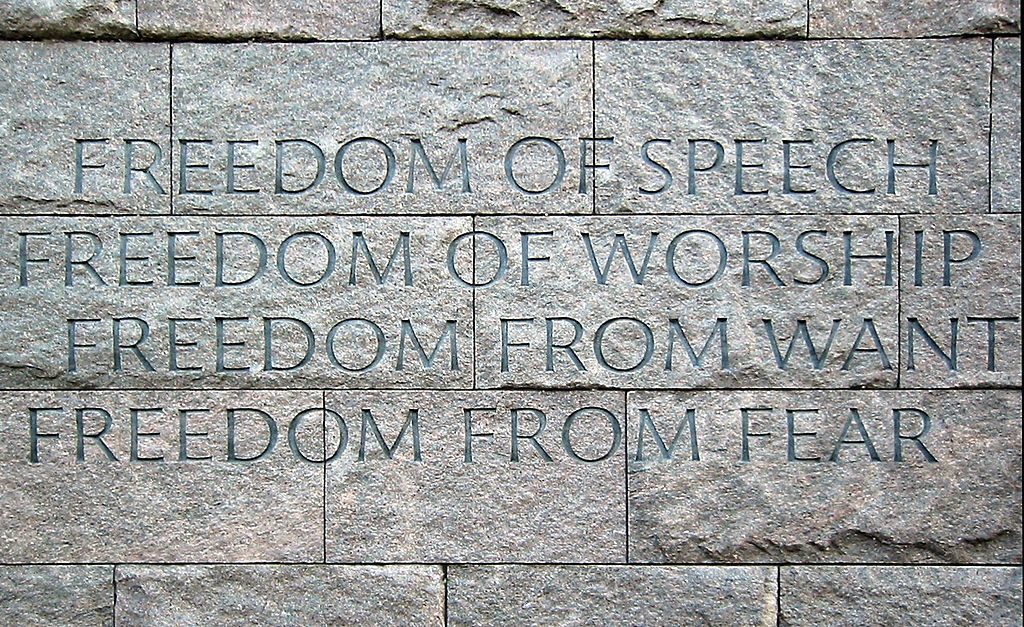

wikipedia cc

Among the books that have been written since, are Mary Ann Glendon’s book, A World Made New, and Johannes Morsink’s book The Universal Declaration of Human Rights Origins, Drafting & Intent. Both works tell the story of the how the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was created.

Glendon’s book also happens to be one of the few sources where the early drafts of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights can be found.

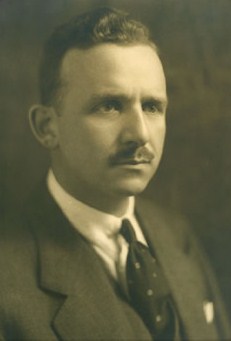

A particularly interesting draft is the very first draft produced by John Humphrey. John Humphrey was the Director of the Human Rights Division of the United Nations Secretariat, which assisted him in preparing the draft. For obvious reasons, Glendon, does not reproduce the hundreds of pages of notes and sources that accompanied that first draft. Many of the basic rights found in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights were set down in that first draft. Humphrey drew them from a wealth of materials including constitutions and proposals that had been submitted to the Secretariat.

The preamble of the the first draft is particularly notable. While much of Humphrey’s ‘rights’ were incorporated into the final version, much of his preamble disappeared as the drafting process continued.

The original preamble is reproduced below.

The preamble of the first version

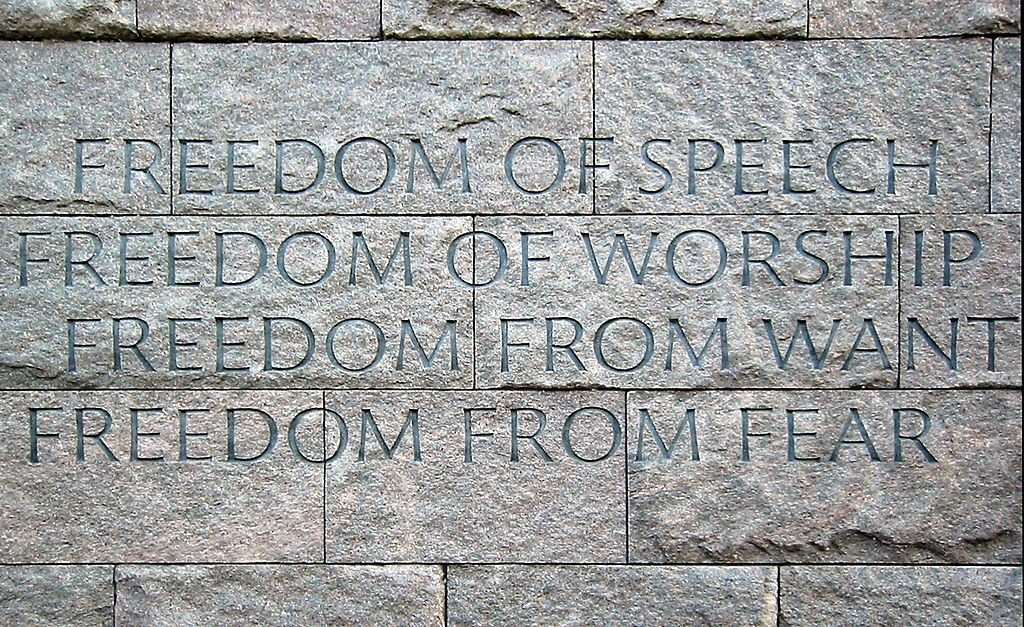

The Preamble shall refer to the four freedoms and to the provisions of the Charter relating to human rights and shall enunciate the following principles:

1. That there can be no peace unless human rights and freedoms are respected;

2. That man does not have rights only; he owes duties to the society of which he forms a part;

3. That man is a citizen both of his State and the world;

4. That there can be no human freedom or dignity unless war and the threat of war is abolished.

The four freedoms are freedom of speech; freedom of worship; freedom from want and freedom from fear. The four freedoms appeared in a 1941 speech by President Franklin Roosevelt. They were to become central war aims of the allied powers, which constituted the “United Nations” during the Second World War.

The four freedoms were among the factors that led to inclusion of human rights concepts in the United Nations Charter. These beginnings led to the work on the Declaration that Humphrey was called on to begin and others continued.

man is a citizen of … the world

Most striking in his first draft is the observation that “man is a citizen both of his State and the world”.

By the next draft, prepared by the French lawyer, René Cassin, this language disappears.

The loss of the concept of world citizenship is significant, given the increasing divergence between citizen rights and human rights. Despite the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a practical guarantee of rights often still depends on national citizenship. Further the practical denial of human rights is often connected with absence of a relevant national citizenship. Had the concept of world citizenship survived, the stranglehold of national citizenship might not be so pervasive.

A right to emigrate

It is also interesting to note that a potentially stronger concept appearing in the first draft is weakened by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights itself. In Humphrey’s draft article 10 states: The right of emigration and expatriation shall not be denied. This concept appears in article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the weaker concept that “Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.” Emigration is more suggestive. Perhaps it would have founded stronger obligations of receiving states.

Peace and Human Rights

Also notable in this first draft are the mirror opposites of peace and war. Humphrey connects these concepts with the realization of human rights. He identifies a feed-back loop between peace and human rights. No human rights – no peace – so, implicitly, we must have rights. No peace – no human rights – so, implicitly, we must have peace. Cassin preserves this concept in his second draft.

A recognition of the first half of the chain of causation, further survived into the preamble of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in a more elaborate form.

The mirror concept that human rights cannot survive in conditions of war or threat of war disappeared. This is regrettable, as clearly the second half of the loop is as correct as it is significant. Martin Luther King Jr. was to come to the same conclusions as his journey through the civil rights movement ultimately led to him to speak out in opposition to the Vietnam War. The loss is also curious in the context of the UN Charter itself. The Charter refers to its goal of protecting succeeding generations from the “scourge of war”.

Instead the preamble of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states:

Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law,

This concept, introduced after lengthy debate about whether the Declaration should contain a “right of rebellion”, arose from the substantive article 29 in the Humphrey draft. That article affirmed the right to “resist oppression and tyranny”. While not explicit in ratifying violence, it was interpreted as having such a potential. In the context of the post-war 1940’s, the delegates lacked unanimity whether there should be such a “right”. Ultimately they decided that rebellion was not a “right”, it was however a “last resort”, and they recorded it as such in the preamble.

So taken together, Humphrey’s unqualified concept for an end to war in his original preamble was replaced with a more conflicted concept. That concept runs: “in the last resort” – no human rights – peace might need to be sacrificed – then we shall have human rights.

It is interesting to note that these conclusions depart from the enlightenment declarations (the US Declaration of Independence and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen). In the 18th century, neither the US Continental Congress nor the French National Assembly had any hesitation in asserting a right to rebellion against tyranny into their Declarations.

By 1948 we see that human rights and violence are beginning to part company. There has been plenty of violence justified by human rights claims since: whether we think of the process of decolonization or more recent justifications of “humanitarian intervention”. Nonetheless the bulk of human rights work since the Declaration has been carried on by pacific means. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights set a direction away from violence that has strengthened over time.

Humphrey’s draft also reminds us that human rights become a nonsense, if they are allowed to be used to violate human rights. This point is made by the Universal Declaration itself.

Further, the enlightenment declarations are not the only sources of human rights. There are other non-violent pedigrees for human rights. We see these non-violent pedigrees for example expressed the U.S. civil rights movement. Similarly, in the work of Bartolome de las Casas, an early advocate of human rights. In the struggle to abolish the slave trade; and in the example of Lucretia Mott and her work for women’s movement. All of these examples of human rights advocacy were pursued without resort to violence. Non-violent methods have been the primary tools of the human rights movement, even before the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Interestingly in 2014, the International Day of Peace was dedicated to “the Right of Peoples to Peace”. It marked a commemoration of the 30th anniversary of the UN General Assembly’s Declaration of the Right of Peoples to Peace. That Declaration completes the idea against war that Humphrey first introduced but which was later lost.

The Right to Peace should be recognised as a supplementary amendment to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This is an implication we can draw from the Humprey’s draft. The Declaration on the Right of Peoples to Peace is reproduced below.

Declaration on the Right of Peoples to Peace

Approved by General Assembly resolution 39/11 of 12 November 1984

The General Assembly ,

Reaffirming that the principal aim of the United Nations is the maintenance of international peace and security,

Bearing in mind the fundamental principles of international law set forth in the Charter of the United Nations,

Expressing the will and the aspirations of all peoples to eradicate war from the life of mankind and, above all, to avert a world-wide nuclear catastrophe,

Convinced that life without war serves as the primary international prerequisite for the material well-being, development and progress of countries, and for the full implementation of the rights and fundamental human freedoms proclaimed by the United Nations,

Aware that in the nuclear age the establishment of a lasting peace on Earth represents the primary condition for the preservation of human civilization and the survival of mankind,

Recognizing that the maintenance of a peaceful life for peoples is the sacred duty of each State,

1. Solemnly proclaims that the peoples of our planet have a sacred right to peace;

2. Solemnly declares that the preservation of the right of peoples to peace and the promotion of its implementation constitute a fundamental obligation of each State;

3. Emphasizes that ensuring the exercise of the right of peoples to peace demands that the policies of States be directed towards the elimination of the threat of war, particularly nuclear war, the renunciation of the use of force in international relations and the settlement of international disputes by peaceful means on the basis of the Charter of the United Nations;

4. Appeals to all States and international organizations to do their utmost to assist in implementing the right of peoples to peace through the adoption of appropriate measures at both the national and the international level.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and spirit of brotherhood and sisterhood

Something absent in Humphrey’s draft that appears in the next draft and becomes central to the Universal Declaration itself is the concept of human solidarity: the spirit of brotherhood and the human family. So while we miss out on ‘world citizenship’ of the Humphrey’s first draft, the Universal Declaration gives us something else. In some ways it is more profound. Cassin introduced the concept in his second draft, in the words: All men, being members of one family are free, possess equal dignity and rights, and shall regard each other as brothers.

In the Universal Declaration itself, it appears as a definition of the human person and of the relationship of human beings to one another:

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

While its drafting was influenced by Cassin’s French heritage, the final language of article 1 is most closely connected in intent is to the slogans of those who worked to abolish the slave trade. “Am I not a Man and a Brother? Am I not a Woman and a Sister?” These abolitionist questions suggest the answer that after two centuries the Universal Declaration was, finally, to give.

Bibliography

Mary Ann Glendon, A World Made New Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Random House New York, 2001

Johannes Morsink, The Universal Declaration of Human Rights Origins, Drafting & Intent, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999