Why Global Citizenship?

Plutarch said:

… nature has given us no country as it has given us no house or field.

… Socrates expressed it … when he said, he was not an Athenian or a Greek, but a citizen of the world (just as a man calls himself a citizen of Rhodes or Corinth).[1]

Plutarch urged his audience to become conscious of a wider reality and to exercise their imagination to overcome a narrow, localised conception of their identity. That is the role of my global citizenship claim too.

Plutarch and Socrates did not conceive of the world as a globe,[2] as I do: I have travelled across the world; my children are trial citizens; I have instant access to global communication.

I had the unique privilege of assisting about 150 refugees on Nauru to complete their application forms. They sought refuge in Australia. But they were repelled because they were Suspected Unauthorised Non-Citizens. The “SUNCs” and I were equally human beings. The difference between us was simple: I was an Australian citizen and they were not.

Writing this essay, I asked myself the question what is accomplished by having a global citizenship concept?[3]

I had set out to do four things by way of answer: first, establish that global citizenship is necessary; second, refute the statist critique of global citizenship; third, demonstrate global citizenship as an emergent reality; and fourth, say what it will look like. Satisfied I had accomplished the first three, I failed the fourth. Then, as I struggled, an unexpected picture, which puzzled and thrilled me, emerged from the fog: global citizenship requires action, not explanation, to manifest. It is something that must be done not described.

2. “Global citizenship”

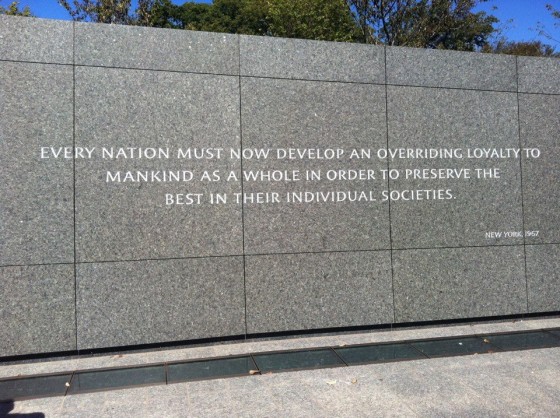

Thomas Paine wrote “my country is the world”.[4] Bahá’u’lláh, the founder of the Bahá’i faith, said “The earth is but one country, and [hu]mankind its citizens”.[5] Kant argued that the jus cosmopoliticum obliges all human beings to “extend hospitality to strangers as fellow ‘citizens of a universal state of humanity’…”[6] By using the term “global citizenship”, I intend to invoke a similar perspective.[7] I use it as a “critical trope” to challenge the notion that citizenship will, or ought to, stop at national citizenship,[8] to “remind citizens of the unfinished moral business of the sovereign state and draw their attention to the higher ethical aspirations which have yet to be embedded in political life”.[9]

“Citizenship” can be used to describe a number of “discrete but related phenomena”.[10] For example, formal citizenship laws tell us who society has deemed fit to vote.[11] But laws are neither fixed nor neutral.[12] The legal status of citizenship is, ideally, an expression of a polity’s conception of membership and collective identity. There are “strong forces” maintaining the nation-state as the ultimate site of citizenship and the manner in which citizenship status is conveyed as a birthright.[13] But legal status is only the manifestation of the less tangible aspects of citizenship. I therefore look for an emergent form of global citizenship, which can be transformed into future legal status.

Language defines how we see the present. By investing in new linguistic meaning, we affect the future.[14] I agree that “[t]here is a great deal at stake … in the way we use the term citizenship”.[15]

My conception of “global citizenship” is consciously both empirical and moral:[16] it is a way of seeing what is emerging and creating what ought to be. It is intended to be not explanatory but evocative, a call to “performative citizenship” as a way of creating the future.[17] Like David O’Byrne’s, my “global citizenship” is intended to move from theoretical possibility[18] to pragmatic reality.[19]

I will argue the transition to global citizenship is a necessary development. And performative global citizenship requires action to bring what is necessary into reality.

3. Global citizenship is necessary

National citizenship is inherently exclusive and divisive. It privileges compatriots at the expense of non-citizens. When one country declares war on another, the citizens of the first country are at war with the citizens of the second,[20] and they may be enlisted to kill each other. The citizen may freely move in and out of her country, but the non-citizen meets razer-wire fences. This is causally related to global inequality and poverty.[21]

Australian citizenship as “ethnic” entitlement

A person born in Australia, “the lucky country”, to at least one Australian citizen parent is an Australian citizen by birthright (a true-blue Aussie).[22] A person born today, outside Australia, to a true-blue Aussie parent is entitled to acquire citizenship by application.[23] These mechanisms ensure that citizenship is passed by true-blue Aussies to their children, at birth, as an entitlement.

Ayalet Shachar describes citizenship entitlement of this kind as more characteristic of an “ethnic” nation, in which “intergenerational continuity [figures] prominently in the reproduction of the collective”,[24] than a “civic” nation, in which “choice and consent … play a key role in the acquisition of membership”.[25]

Choice and consent play a far greater role for the citizen “by conferral”[26] who has migrated to Australia. She must first find a “migration pathway” to become a permanent resident.[27] Then, she must satisfy a residence requirement.[28] Unless exempt,[29] she must pass the citizenship test.[30] Finally, she must be likely to reside in Australia, or maintain a close and continuing connection to it, (what Shachar might call a jus nexi requirement[31]) and be of good character.[32] She must pledge her commitment to Australia.[33] The permanent residence criterion for citizenship by conferral is the most difficult of these to meet.

In 2009-10, 107,868 skilled migrants were granted permanent residence in Australia.[34] There were also 13,770 humanitarian visas granted.[35]

But the vast majority of Australian citizens drew citizenship in the birthright lottery; they deserved it no than the colour of their eyes. As far as lottery tickets go, it’s the jackpot: Australia is the second most developed country in the world.[36]

National citizenship and exclusion

National citizenship is inherently exclusive.[37] That is so in Australia. The Commonwealth Constitution was constructed on a bedrock of racism and rejection of “the other”:[38] “[c]itizenship in the 1890s was a matter of exclusion rather than inclusion”.[39] In 1947, two per cent of Australian residents were born outside of Australia, the British Isles or New Zealand.[40] The recent introduction of the citizenship test[41] was attended by “vague button-pushing and dog-whistling about Australian values”.[42] The second reading speech emphasised the need for integration[43] into “our way of life”.[44] The test was divisive – designed “to separate people into one group that is deserving of Australian citizenship and another group that is not deserving”[45] and to send “a message about excluding people from being able to be citizens”.[46]

National citizenship demands the equal treatment of citizens[47] and the differential treatment of non-citizens. For example, the Migration Act 1958 is founded on discrimination between citizens and non-citizens.[48] A non-citizen may be granted a visa[49] allowing her to enter or remain in Australia. Without a visa, she cannot travel to Australia,[50] she may be detained,[51] even indefinitely,[52] or removed.[53] Thus, abuse of human rights recognised by international agreement is allowed by Australia against human beings who are non-citizens.[54]

This discrimination influences constitutional law as well. For example, the High Court has derived a principle from Chapter III of the Constitution that “the ‘exceptional cases’ aside, the involuntary detention of a citizen in custody by the State is permissible only as a consequential step in the adjudication of criminal guilt of that citizen for past acts.”[55]

In Ruddock v Vadarlis,[56] French J (with whom Beaumont J agreed) held that:

… the Executive power of the Commonwealth, absent statutory extinguishment or abridgement, would extend to a power to prevent the entry of non-citizens and to do such things as are necessary to effect such exclusion. … The power to determine who may come into Australia is so central to its sovereignty that it is not to be supposed that the Government of the nation would lack under the power conferred upon it directly by the Constitution, the ability to prevent people not part of the Australia [sic] community, from entering.[57]

This discrimination contradicts the promise of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:[58] “[a]ll human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights”;[59] “[e]veryone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind” (including national origin);[60] “[a]ll are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law”;[61] everyone has the right to not be subjected to arbitrary detention.[62] It is a basic premise of most human rights treaties that citizens and non-citizens will be treated alike, subject to appropriate exceptions.[63] For example, the “general rule is that each one of the rights of the [International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights] must be guaranteed without discrimination between citizens and aliens”.[64] But many non-citizens still face discrimination, and non-citizens are particularly vulnerable to arbitrary detention.[65]

The fundamental principle of international human rights law – that all humans are born equal in dignity and rights – derives from the “golden rule”, a moral precept common to religions and ethical codes across the globe. Both fundamental principle and golden rule are thwarted by the exclusionary project of national citizenship

National citizenship and global inequality

Not only does national citizenship legitimate unequal protection of rights, it is responsible for the unequal distribution of global wealth.[66]

The usual objection to opening borders – that people with less opportunity would come to Australia[67] – is founded on the premise that Australians are entitled to enjoy better living conditions than our neighbours. The argument that each wider concentric circle of citizenship necessarily evokes a lesser set of citizenship duties is not morally justifiable.[68] Any value that exclusivity might be seen to confer on citizenship[69] does not outweigh the global injustice caused by citizenship as discrimination.

Only 3.1 per cent of the world’s population reside outside their country of birth.[70] Citizenship of a “lucky country” is therefore an incredibly valuable commodity, acquired by most on the basis of “a morally arbitrary set of criteria”.[71] National jus soli and jus sanguinis citizenship laws “perpetuate and reify dramatically differentiated life prospects”.[72] Shachar powerfully invokes William Blake: “Some are born to sweet delight, Some are born to endless night”.[73] She analyses citizenship as a form of property, transmitted at birth. She,[74] and others,[75] argue that a globally regulated tax or dividend should be paid, by those born in lucky countries, to poorer countries by way of aid.

Pogge argues that favouring one’s compatriots is a global form of nepotism, and that it is as morally unacceptable as a public official favouring her child.[76] What he calls “explanatory nationalism” – an approach which explains that national governments are ultimately responsible for global inequality – allows us (the lucky) not to see any connection between our actions and global poverty.[77] “How”, he asks, “can our ever so free and fair agreements with tyrants give us property rights in crude oil, thereby dispossessing the local population and the rest of humankind?”[78] By these and other actions of our governments, we are, he argues, deeply implicated in the harms caused by tyrannical regimes.

The easiest focal point for global inequality is poverty.[79] 1 billion children worldwide are deprived of services essential to survival and development; in 2008, 8.8 million children died worldwide before their fifth birthday.[80] In 2009, global military expenditure was $ US 1531 billion;[81] the same year, the G8 countries provided only $US 82.175 billion in development funding.[82]

Pogge finishes his book with these two sentences: “[world poverty] kills one-third of all human beings born into our world. And its eradication would require no more than 1 percent of the global product.”[83]

In a recent research paper for the World Bank, Branko Milanovic analysed income data from 120 countries.[84] 80 per cent of variability in incomes around the world is determined by (i) place of birth and (ii) parental income. Once a person’s income class is determined, their country of residence accounts for 95 per cent of variability in their income. In many countries, the mean income is so low that the wealthiest class earns less than the poorest class in a more affluent country. For example, India’s income distribution runs from $PPP 200 to $PPP 2,000; the United States’, $PPP 2,000 to $PPP 70,000. Milanovic has also analysed the changes in global inequality between 1820 and 2002.[85] He found that global inequality increased from 43-45 Gini points[86] in the early 19th Century to 65-70 today. And “[e]ven more remarkable is that the composition of global inequality changed from being driven by class differences within countries to being driven by locational income differences (that is, by the differences in mean country incomes)”.[87]

Globalisation has increased and entrenched global inequality.[88] This is despite two recent changes making global inequality even more difficult to justify: practically, the opportunity cost of shifting global income distribution to eradicate poverty is much less than it would have been fifty years ago; philosophically, moral universalism has replaced colonial and imperial attitudes to rights.[89]

“Radical inequalities” – that is, “global inequalities that are absolutely extreme, relatively extreme, persistent, pervasive, and avoidable” – are inherently objectionable, and place a moral obligation on those at the top of the pile to do something.[90] I agree with Pogge that “[b]y helping to impose the present global institutional order, we are participants in the largest human-rights violation in human history.”[91] Cruelly, “[e]ven as citizenship is multiplying and transforming, dualizing and deterritorializing, for those without citizenship, there is less than ever”.[92]

4. Refuting the statist critique

Citizenship is not inherently national

Against the claim of global citizenship, it has been asserted that citizenship is necessarily a national enterprise.[93] There is nothing about citizenship that is inherently and inevitably restricted to the nation-state.[94]

The Howard Government’s citizenship test promoted Australian “citizenship as the single most unifying force in our community”;[95] such a claim is unrealistic in a modern world.[96] With instantaneous global information and communication, affiliations unrelated to state boundaries are “often, and increasingly, experienced as primary”.[97] For example, religious identification is often experienced more strongly than national identity.[98] Young Australians may be more loyal to an NGO, international corporation or pop star than to their country.

As nations become more defined by each other and their interrelationship, our national identity becomes more global.[99] The national citizen’s duties extend beyond borders because she is responsible for the nation’s actions, and the nation has obligations beyond its borders.[100] The fact of “compatriot partiality” does not require the abandonment of cosmopolitanism; rather, cosmopolitanism can inform our understanding and conceptualisation of patriotism.[101]

Three “spheres” of citizenship

Blank has identified three territorial “spheres of citizenship”, each with its own internal logic.[102]

Local spheres of citizenship – which in Australia would comprehend municipalities, States and territories – are defined by the logic of mere presence, what Blank calls jus domicile:[103] local citizenship is attained primarily, or merely, by residence. Its character is “civic”, by contrast to the “ethnic” character of national citizenship. Local citizenship holds greater possibilities for political participation.[104]

National citizenship – still largely regulated by jus soli and jus sanguini – “remains arcane and based either on unfounded mystique or defunct racism”.[105]

As to the global sphere, Blank points out that the territorial boundaries of the world are more definite and real than national boundaries.[106]

National citizenship and global citizenship not mutually exclusive

There is no reason national citizenship cannot exist within global citizenship, in the same way that local citizenship currently exists within national citizenship.[107] Indeed, citizenship’s evolution suggests that as the likely course: Socrates was Athenian and Greek; in 1901, the separate Australian colonies became States within the Commonwealth; since then, the countries of Europe have become member states of the European Union. There is nothing magical about the nation-state to preserve it eternally from absorption into a regional or global community. If it were absorbed, the nation-state would not be abolished. National citizenship and global citizenship “form a continuum whose contours, at least, are already becoming visible”.[108]

Pogge argues for an institutional cosmopolitanism which – by re-setting the “economic ground rules that regulate property, cooperation, and exchange and thereby condition production and distribution”[109] – would disperse sovereignty “in the vertical dimension”.[110] He argues, by analogy to federalist regimes, that vertical dispersal of sovereignty is just as important as horizontal dispersal (between different arms of government).[111] John Hoffman has argued that “[e]ach layer, if it is democratically constructed, strengthens the other. Global citizenship … does not operate in contradiction with regional, national and local identities. It expresses itself through them.”[112]

When global citizenship is conceptualised in such a way that it would transform, rather than end, nation-state citizenship, many of the statist attacks on global citizenship fall away.

- Global citizenship is not incoherent:[113] only some incidents of citizenship will transfer from the state to the globe, and the transfer will be iterative and gradual.

- I agree that, presently, “international repercussions furnish compelling rationales for nationality”.[114] Global citizenship need neither deprive the global citizen of a nationality nor deprive international law of the nation to protect global citizens.

- Nor is there any psychological difficulty with overlapping identities as a national and world citizen.[115] Surveys done in 2000 revealed that 15 percent of the world’s inhabitants identified most strongly with the global sphere, only 38 percent with the national and 47 percent with the local.[116]

Seeing global citizenship emerging

Performative global citizenship is aided by the image of the future emerging in the present. Global citizenship is emerging in many places, but its character is distinct from that of national citizenship. Some examples follow.

- In 1993, Richard Falk identified five different extant pictures of global citizenship: the global reformer; the man of transnational affairs;[117] the response to global environmental ecologic and economic issues; the rise of regional political consciousness; and the emergence of transnational activism.[118]

- In 10 years time the economic contribution of the 107,868 skilled migrants who became permanent residents in Australia in 2009-10 will be $11.6 billion.[119] Australia has made an economic decision to let these persons through the migration gateway because they have something to offer which the Australian demos finds desirable. Citizenship entitlement for them is more “civic” in character than the “ethnic” entitlement of the true-blue Aussie. The criteria for membership are not arbitrary; the process resembles merits-based employment in a global market.

- As multiple nationalities become a global reality, the notion of exclusive identification is challenged.[120]

- Blank suggests that the logic of national citizenship is gravitating towards the logic of local citizenship, with many countries adopting residency tests for provision of social and economic rights.[121]

Socrates and Plutarch’s consciousness was limited by their constrained understanding of the world. Now, the rapid expansion in global communication and information flows has induced a global consciousness.[122] The more conscious we are of similarities between ourselves and members of other nations, the way in which the activities of nations affect one another, and the global challenges faced by all peoples, the greater the capacity for collective identity across national borders. [123] Global consciousness is creating a transnational identity, which is forming the basis for global citizenship. Communication media like Facebook make it possible to have a global community accessible from a mobile telephone. New global communities are coming to life, structured around common interests and concerns rather than physical proximity.[124] Globalisation has allowed “social and cultural identity to roam freely … beyond the limitations” imposed by the “nation-state”.[125]

It has been said that the existence of international law rights does not sustain a concept of global citizenship because the rights are enforceable only by nation-states.[126] But this argument confuses the existence of rights with their enforceability: the existence of a right and the manner in which it is enforced must be considered separately. A global citizen can already directly access international institutions for the enforcement of her rights. For example, she can send a communication to the Human Rights Committee under the First Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.[127] It is true that a negative finding by the Committee is politically, rather than legally, enforceable. But this does not make it is ineffective.[128] The Committee’s opinion in Toonen v Australia[129] undoubtedly led to the Commonwealth’s legislative over-riding of the Tasmanian law criminalising homosexuality.[130] Although it did not lead to legislative change, the Committee’s opinion in A v Australia[131] – to the effect that long detention of asylum seekers was arbitrary – gave national refugee advocates a strong external standard by which to criticise Australia’s detention policies. As global institutions become stronger, nations will be increasingly compelled to enforce international rights.[132]

International rights are being enforced in the local sphere.[133] As a Victorian citizen, my “negative” international law rights are recognised by Part 2 of the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006. Despite difficulties, these rights have been enforced to an extent.[134] International law is regularly cited, with mixed reactions by the judiciary.[135]

5. Imagining/creating the future

I have argued that global citizenship is a necessary development – as a matter both of morality and survival.

National citizenship is necessarily exclusive; global citizenship is necessarily inclusive. Each human being has a claim to global citizenship, and to have the same rights and opportunities as each other. There is no foundation for exclusion of a human being from the global citizenry. This makes global citizenship a necessity if the promise of the golden rule and international human rights law is to be fulfilled.

Human beings now experience global problems. I have discussed global inequality and poverty. Another example is climate change. It is clear that environmental degradation positively influences migration numbers[136] and will create problems requiring a global solution. The treatment of ecological refugees will be “a key terrain over which [inclusion and exclusion are] negotiated and accomplished.”[137]

In those circumstances, it is unhelpful to justify the status quo by explanatory nationalism. An exercise of imagination is required, to see new possibilities for the future, to make “a One-World Community … an emergent possibility”.[138]

Attempts at imagining the future

This can include imagining global institutions.

The failure of the UN climate change conference held in Copenhagen in December 2009 has led to calls for a specific UN parliamentary assembly.[139] Daniele Archibugi has proposed a global democracy with five dimensions: local, state, inter-state, regional and global.[140] The aim: to pursue “democracy at different levels of governance that are mutually autonomous but complementary”.[141] Majid Tehranian has also proposed democratic global governance, arguing that global democracy “must deepen democratic participation at the lower levels (local, national, regional), while broadening it at the higher level of global decision-making”.[142] These and other imaginative attempts are performative acts of global citizenship.

They are sometimes restricted in their imaginative reach by the ever-present mould of national citizenship. It is a mistake to think that global citizenship will look like national citizenship. The difficult task is to see its unique structure, still largely invisible, in the contours of what is becoming visible.[143]

Open borders and jus domicilis

As an act of performative global citizenship, I imagine a future without policed national borders. I am not alone. Veit Bader argues that until wealthy nations give sufficient financial assistance to poor countries, they are morally obliged to provide “fairly open” borders.[144] Steve Cohen attacks the notion of “fair” immigration controls, arguing that immigration controls were not historically inevitable, but were driven by wealthy nations trying to capture world markets and regulate world labour.[145]

The advent of multiple citizenship, developments in the European Union,[146] the increased opening of borders for skilled migration and the rapid pace of globalisation gesture, in my imagination, towards more open borders and a jus domicilis basis for national citizenship – first as an additional, and eventually as a preferable, basis for national citizenship. An extant step on the way is Shachar’s jus nexi.[147]

The mystic jus sanguinis and jus soli bases of citizenship, along with internal freedom of movement, properly belong to the globe. We are all born on the same earth, to human beings of the same species; we all “travel together, passengers on a little space ship, dependent on its vulnerable reserves of air and soil”.[148] This is the natural evolution – from the city-state to the nation-state to the regional, through the international, to the global as the proper, inclusive, site of ultimate identity and equality.

6. Conclusion – global citizenship as performance

I have mentioned imaginative gestures towards the shape of global citizenship. Ultimately, they are exciting to me because of what they do, not what they say.

Plutarch, citing Socrates’ example, urged his audience to imagine.

Global citizenship is an emerging empirical reality and a moral necessity. But the transformation from national to global citizenship is too delicate, too fraught, to happen on its own. It requires imagination and conscious action by the global citizenry to create it. We can observe the necessity, the emergence, the possibility, but beyond that it cannot be explanatory, it must be performative.

As Nelson Mandela said recently:[149]

Like slavery and apartheid, poverty is not natural. It is man-made and it can be overcome and eradicated by the actions of human beings.

And overcoming poverty is not a gesture of charity. It is an act of justice. It is the protection of a fundamental human right, the right to dignity and a decent life.

While poverty persists, there is no true freedom.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

(see footnotes for web addresses)

Articles, chapters, papers, reports etc

Afifi, Tamer and Koko Warner, The Impact of Environmental Degradation on Migration Flows across Countries (2008)

Bader, Veit, “Fairly Open Borders” in Citizenship and Exclusion (1997) 28

Benhabib, Seyla, “Twilight of Soverignty or the Emergence of Cosmpolitan Norms? Rethinking Citizenship in Volatile Times” in Faist and Kivisto (eds), Dual Citizenship in Global Perspective: From Unitary to Multiple Citizenship (2007) 247

Blank, Yishai, “Spheres of Citizenship” (2007) 8 Theoretical Inquiries in Law 411

Bosniak, Linda “Citizenship Denationalised” (2000) Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies 447

Bummel, Andreas, Fernando Iglesias and Duncan Kerr, Democratizing Global Climate Policy through a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly (2010)

Charlesworth, Hilary, Human Rights: Australia versus the UN (2006)

Chubb, Ian, “Inaugural annual address on immigration and citizenship” 22 Public Administration Today 8

Dauvergne, Catherine, “Refugee Law and the Measure of Globalisation” (2005) 22(2) Law in Context 62

Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Annual Report 2009-10 (2010)

Falk, Richard, “The Making of Global Citizenship” in Brecher, Childs and Cutler (eds), Global Visions: Beyond the New World Order (1993) 39, 41-8.

Golmohamad, Muna, “Education for World Citizenship: Beyond national allegiance” (2009) 41(4) Educational Philosophy and Theory 466

Harris Rimmer, Susan, “Examining the character of Australian citizens” (2009) 20 (2) Public Law Review 95

International Organization for Migration, “Facts and figures, global estimates and trends”

Kluvers, Ron and Pillay, Soma, “Participation in the budgetary process in local government” (2009) 68(2) Australian Journal of Public Administration 220

Legomsky, Stephen, “Why Citizenship” (1994) 35 Virginia Journal of International Law 279

Milanovic, Branko, Global inequality of opportunity: How much of our income is determined at birth? (2009)

Milanovic, Branko, Global Inequality and the Global Inequality Extraction Ratio: The Story of the Past Two Centuries (2009)

Muskoka Accountability Report: Assessing action and results against development-related commitments (2010)

Nolan, Mark and Rubenstein, Kim, “Citizenship and Identity in Diverse Societies” (2009) 15 Humanities Research 1

Rubenstein, Kim, “Citizenship in an Age of Globalisation: The Cosmopolitan Citizen” (2007) 25(1) Law in Context 88

Rubenstein, Kim, “Citizenship in the Constitutional Convention Debates: A Mere Legal Inference?” (1997) Federal Law Review 295

Rubenstein, Kim “The Lottery of Citizenship: The Changing Significance of Birthplace, Territory and Residence to the Australian Membership Prize” (2005) 22(2) Law in Context 45

Shachar, Ayalet, “The Worth of Citizenship in an Unequal World” (2007) 8 Theoretical Inquiries in Law 367

Shue, Henry, “Global Accountability: Transnational Duties Towards Economic Rights” in Coicaud, Doyle and Gardner (eds), The Globalization of Human Rights (2003) 160

Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, SIPRI Yearbook 2010 (2010)

Tehranian, Majid, “Democratizing Governance” in Democratizing Global Governance (2002) 55

UNICEF, The State of the World’s Children (2009)

United Nations Development Program, Human Development Report 2010 (2010)

Vandenberg, Andrew, “Cybercitizenship and Digital Democracy” in Citizenship and Democracy in a Global Era (2000) 289

Walzer, Michael, “Spheres of Affection” in Joshua Cohen (ed), For Love of Country: Debating the Limits of Patriotism (1996), 125.

Weale, Albert, “Citizenship Beyond Borders” in Vogel and Moran (eds), The Frontiers of Citizenship (1991)

Weinrib, Jacob, “Kant on citizenship and universal independence (2008) 33 Australian Journal of Legal Philosophy 1, 10

Weissbrot and Stephen Meili, “Human rights and protection of non-citizens : wither universality and indivisibility of rights?” (2009) 28(4) Refugee Survey Quarterly 34

Williams, John, “Race, Citizenship and the Formation of the Australian Constitution: Andrew Inglis and the 14th Amendment” (1996) 42 Australian Journal of Politics and History 10

Books

Archibugi, Daniele, The Global Commonwealth of Citizens (2008)

Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh (1976)

Carter, April, The Political Theory of Global Citizenship (2001)

Cohen, Steve, No One is Illegal (2003)

Dauvergne, Catherine, Making People Illegal (2008)

Habermas, Jürgen, Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy (1996)

Hanafan, Patrick, Constituting Identity (2001)

Hoffman, John, Citizenship Beyond the State (2004), 130.

Hutchings, Kimberley and Dannreuther, Roland (eds), Cosmopolitan Citizenship (1999)

Kinley, Civilising Globalisation (2009)

Paine, Thomas, Rights of Man (1792)

Plutarch, Plutarch’s Morals: Vol 3 (corrected and revised by William Goodwin, 1878)

Pogge, Thomas, World Poverty and Human Rights (2008)

Rubenstein, Kim, Australian Citizenship Law in Context (2002)

O’Byrne, David, The Dimensions of Global Citizenship (2003)

Shachar, Ayalet, The Birthright Lottery: Global Citizenship and Global Inequality (2009)

Tan, Kok-Chor, Justice Without Borders (2004)

Case law

Al-Khateb v Godwin (2004) 219 CLR 562

Castles v Secretary to the Department of Justice [2010] VSC 310.

Chu Kheng Lim v MILGEA (1992) 176 CLR 1

Fardon v Attorney General (Qld) (2004) 223 CLR 575

Kracke v Mental Health Review Board & Ors [2009] VCAT 646

Ruddock v Vadarlis (2001) 110 FCR 491.

South Australia v Totani [2010] HCA 39

WBM v Chief Commissioner of Police [2010] VSC 219.

Legislation

Australian Citizenship Act 2007

Migration Act 1958

International law

A v Australia [1997] UNHRC 7; CCPR/C/59/D/560/1993 (30 April 1997)

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, General Comment No. 15: The position of aliens under the Covenant, 11/04/1986

Toonen v Australia, [1994] UNHRC 15; CCPR/C/50/D/488/1992 (4 April 1994)

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, GA Res 217A (III), UN Doc A/810 (1948).

Other

Nelson Mandela, Speech for Make Poverty History Campaign, 3 February 2005

[1] Plutarch, Plutarch’s Morals: Vol 3 (corrected and revised by William Goodwin, 1878), 18-9.

[2] As to the evolution of cosmopolitanism, see Kimberly Hutchings, “Political Theory and Cosmopolitan Citizenship” in Hutchings and Dannreuther (eds), Cosmopolitan Citizenship (1999) (Hutchings) 3; David O’Byrne, The Dimensions of Global Citizenship (2003), 55-79.

[3] Cf Stephen Legomsky, “Why Citizenship” (1994) 35 Virginia Journal of International Law 279, 285.

[4] Thomas Paine, Rights of Man (1792), 472.

[5] Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh (1976), 250.

[6] Andrew Linklater, “Cosmopolitan Citizenship” in Hutchings, n 2, 35, 39.

[7] See also Linda Bosniak, “Citizenship Denationalised” (2000) Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies 447, 448 and 495.

[10] Kim Rubenstein, “Citizenship in an Age of Globalisation: The Cosmopolitan Citizen” (2007) 25(1) Law in Context 88, 89-90; Bosniak, n 7, 455.

[11] Immanuel Kant thought the only qualification for citizenship was fitness to vote (see, generally, Jacob Weinrib, “Kant on citizenship and universal independence (2008) 33 Australian Journal Of Legal Philosophy 1, 10), which rather begs the question.

[12] See Kim Rubenstein, “The Lottery of Citizenship: The Changing Significance of Birthplace, Territory and Residence to the Australian Membership Prize” (2005) 22(2) Law in Context 45, 46-7.

[13] Ayalet Shachar, The Birthright Lottery: Global Citizenship and Global Inequality (2009), 2; Michael Walzer, “Spheres of Affection” in Joshua Cohen (ed), For Love of Country: Debating the Limits of Patriotism (1996), 125.

[14] See Bosniak, n 7, fn 182.

[16] cf David Miller, “Bounded Citizenship” in Hutchings, n 2, 70-2.

[18] Yishai Blank, “Spheres of Citizenship” (2007) 8 Theoretical Inquiries in Law 411, 442.

[21] See, eg, Veit Bader, “Fairly Open Borders” in Citizenship and Exclusion (1997) 28; Thomas Pogge, World Poverty and Human Rights (2008).

[22] Australian Citizenship Act 2007, s 12(1)(a).

[23] Ibid, s 16(1) and (2)(a).

[24] Ayelet Shachar, “The Worth of Citizenship in an Unequal World” (2007) 8 Theoretical Inquiries in Law 367, 372.

[26] Australian Citizenship Act 2007, Subdivision B, Division 2, Part 2.

[28] Ibid, ss 21(2)(c), 22, 22A and 22B, unless she has completed relevant defence service: s 23.

[30] Ibid, s 21(2(d)-(f) and (2)(a).

[31] Shachar, n 13, Ch 6, 164ff.

[32] Australian Citizenship Act 2007, s 21(2)(g) and (h); Susan Harris Rimmer, “Examining the character of Australian citizens” (2009) 20 (2) Public Law Review 95.

[34] Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Annual Report 2009-10 (2010) – downloaded from <http://www.immi.gov.au/about/reports/annual/2009-10/pdf/report-on-performance.pdf>, 46 (all web documents downloaded 1-9 January 2011).

[36] United Nations Development Program, Human Development Report 2010 (2010), Table 1 – downloaded from <http://hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr2010/chapters/en/>.

[37] Bosniak, n 7, 501; O’Byrne, n 2, 37-44.

[38] See, generally, Kim Rubenstein, Australian Citizenship Law in Context (2002), [2.2.1]; Kim Rubenstein, “Citizenship in the Constitutional Convention Debates: A Mere Legal Inference?” (1997) Federal Law Review 295; John Williams, “Race, Citizenship and the Formation of the Australian Constitution: Andrew Inglis and the 14th Amendment” (1996) 42 Australian Journal of Politics and History 10.

[40] Ian Chubb, “Inaugural annual address on immigration and citizenship” in 22 Public Administration Today 8, 11.

[41] Citizenship Act 2007, s 23A.

[42] Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, Senate, 7 February 2007, 22 (Andrew Bartlett).

[43] Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, 30 May 07, 4-5 (Kevin Andrews, Minister for Immigration and Citizenship).

[45] Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, Senate, 13 August 2007, 65 (Kerry Nettle). (See also 7 February 2007, 25.)

[47] See, eg, Kok-Chor Tan, Justice Without Borders (2004), 180-1. Of course, this is not always realised: see, eg, Patrick Hanafan, Constituting Identity (2001), 47-62.

[48] This is laid bare by the objects in s 4. For a list of legislation discriminating on the basis of citizenship, see Rubenstein, n 38, Ch 5.

[49] Migration Act 1958, s 29.

[51] Ibid, ss 178-180 and Div 7, Part 2.

[52] Al-Khateb v Godwin (2004) 219 CLR 562.

[53] Migration Act 1958, s 181 and Div 8, Part 2.

[54] See, eg, A v Australia [1997] UNHRC 7; CCPR/C/59/D/560/1993 (30 April 1997).

[55] Emphasis added. Fardon v Attorney General (Qld) (2004) 223 CLR 575, 612 (Gummow J); South Australia v Totani [2010] HCA 39, [209] (Hayne J). See also Chu Kheng Lim v MILGEA (1992) 176 CLR 1, 29-31 (Brennan, Deane and Dawson JJ).

[58] GA Res 217A (III), UN Doc A/810 (1948).

[63] David Weissbrot and Stephen Meili, “Human rights and protection of non-citizens : wither universality and indivisibility of rights?” (2009) 28(4) Refugee Survey Quarterly 34, 37-47.

[64] Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, General Comment No. 15: The position of aliens under the Covenant, 11/04/1986, [2].

[65] Weissbrot and Meili, n 63, 52-3.

[66] See, generally, Pogge, n 21. From what follows, it is difficult for me to see how it can be said that no-one can “demonstrate how, in fact, the current [world] order is directly [harming the world’s poor]”: David Kinley, Civilising Globalisation (2009), 105.

[67] The morality of this view is discussed in Tan, n 47: see, eg, 123-132.

[69] See Rubenstein, n 38, [5.1.3].

[70] International Organization for Migration, “Facts and figures, global estimates and trends” – downloaded from <http://www.iom.int/jahia/Jahia/facts-and-figures/global-estimates-and-trends>.

[73] William Blake, Auguries of Innocence (c 1807).

[78] Ibid, 148. See also 182-5.

[80] UNICEF, The State of the World’s Children (2009) – downloaded from <http://www.unicef.org/rightsite/sowc/pdfs/SOWC_Spec%20Ed_CRC_Main%20Report_EN_090409.pdf>.

[81] Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Chapter 5 (summary), SIPRI Yearbook 2010 (2010) – downloaded from <http://www.sipri.org/yearbook/2010/05>.

[82] Under the Official Development Assistance Scheme – see Executive Summary, Muskoka Accountability Report: Assessing action and results against development-related commitments (2010) – downloaded from <http://www.g8.utoronto.ca/summit/2010muskoka/accountability/muskoka_accountability_report_executive_summary.pdf>.

[84] Branko Milanovic, Global inequality of opportunity: How much of our income is determined at birth? (2009) – downloaded from < http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTDECINEQ/Resources/Where8.pdf>.

[85] Branko Milanovic, Global Inequality and the Global Inequality Extraction Ratio: The Story of the Past Two Centuries – downloaded from < http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/IW3P/IB/2009/09/09/000158349_20090909092401/Rendered/PDF/WPS5044.pdf>

[86] The Gini co-efficient is a measure of equality.

[88] Henry Shue “Global Accountability: Transnational Duties Towards Economic Rights” in Coicaud, Doyle and Gardner (eds), The Globalization of Human Rights (2003) 160, 168-9.

[92] Catherine Dauvergne, Making People Illegal (2008), 138.

[93] See, eg, Miller, n 16; Bosniak, n 7, 447-448.

[94] See, eg, Bosniak, n 7, and Blank, n 18.

[95] Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, Senate, 24 Nov 2008, 19 (Concetta Fierravanti-Wells), responding to the Labour Government’s changes to the test.

[98] See Mark Nolan and Kim Rubenstein, “Citizenship and Identity in Diverse Societies” (2009) 15 Humanities Research 1, 29.

[99] See Muna Golmohamad in “Education for World Citizenship: Beyond national allegiance” (2009) 41(4) Educational Philosophy and Theory 466, 470-472.

[100] Albert Weale, “Citizenship Beyond Borders” in Vogel and Moran (eds), The Frontiers of Citizenship (1991), 155.

[101] Tan, n 47, 148 and 198. See also Daniele Archibugi, The Global Commonwealth of Citizens (2008), 284.

[104] See, eg, Ron Kluvers and Soma Pillay, “Participation in the budgetary process in local government” (2009) 68(2) Australian Journal Of Public Administration 220.

[107] See O’Byrne, n 2, 121-3.

[108] Jürgen Habermas, Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy (1996), 515.

[110] Ibid, 184. See also Bosniak, n 7, 506.

[112] John Hoffman, Citizenship Beyond the State (2004), 130.

[115] See, eg, Nolan and Rubenstein, n 98, 41 and 42.

[118] Richard Falk, “The Making of Global Citizenship” in Brecher, Childs and Cutler (eds), Global Visions: Beyond the New World Order (1993) 39, 41-8.

[119] Department of Immigration and Citizenship, n 34, 46.

[120] See Nolan and Rubenstein, n 98, 35-6; Rubenstein, n 10; Seyla Benhabib, “Twilight of Soverignty or the Emergence of Cosmpolitan Norms? Rethinking Citizenship in Volatile Times” in Faist and Kivisto (eds) Dual Citizenship in Global Perspective: From Unitary to Multiple Citizenship (2007) 247.

[123] See also Majid Tehranian, “Democratizing Governance” in Democratizing Global Governance (2002) 55, 65-7.

[124] For an outdated, pessimistic take on “cybercitizenship”, see Andrew Vandenberg, “Cybercitizenship and Digital Democracy” in Citizenship and Democracy in a Global Era (2000) 289. Organisations such as GetUp and Avaaz have shown the power of the internet to enhance domestic and global citizenship.

[126] Bosniak, n 7, 467-468; Blank, n 18, 443.

[127] Opened for signature 16 December 1966, [1991] ATS 39 (entered into force 23 March 1976), art 2.

[128] In Al-Khateb v Godwin (2004) 219 CLR 562, McHugh J said at 101, of laws allowing indefinite detention of aliens, that “Parliament and those who introduce them must answer to the electors, to the international bodies who supervise human rights treaties to which Australia is a party and to history” (emphasis added).

[129] [1994] UNHRC 15; CCPR/C/50/D/488/1992 (4 April 1994).

[130] See Human Rights (Sexual Conduct) Act 1994 (Cth).

[131] [1997] UNHRC 7; CCPR/C/59/D/560/1993 (30 April 1997).

[132] See also Blank, n 18, 444-6. For a critical examination of the Howard Government’s approach to adverse decisions by UN bodies, see Hilary Charlesworth, Human Rights: Australia versus the UN (2006) – downloaded from <http://www.democraticaudit.anu.edu.au/papers/20060809_charlesworth_aust_un.pdf>.

[134] See, eg, Kracke v Mental Health Review Board & Ors [2009] VCAT 646 and Castles v Secretary to the Department of Justice [2010] VSC 310.

[135] Compare, eg, Kracke, ibid, to WBM v Chief Commissioner of Police [2010] VSC 219.

[136] See, eg, Tamer Afifi and Koko Warner, The Impact of Environmental Degradation on Migration Flows across Countries (2008), downloaded from <http://www.ehs.unu.edu/file/get/3884>.

[137] Catherine Dauvergne, “Refugee Law and the Measure of Globalisation” (2005) 22(2) Law in Context 62, 76.

[139] Andreas Bummel, Fernando Iglesias and Duncan Kerr, Democratizing Global Climate Policy through a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly (2010) [Conference, “Democratizing Climate Governance”, Australian National University, 15-16 July 2010] – downloaded from <http://www.kdun.org/resources/2010canberra.pdf>. Such ideas are not new. In 1840, an American, William Ladd, called for the creation of an international congress: Archibugi, n 101, 1.

[140] Archibugi, n 101, 89-96.

[142] Tehranian, n 123, 56. See also O’Byrne, n 2, 130-2.

[143] See, also, O’Byrne, n 2, 126-7.

[145] Steve Cohen, No One is Illegal (2003), 241-265.

[146] See April Carter, The Political Theory of Global Citizenship (2001), 119-141.

[147] See Shachar, n 13, Ch 6.

[148] Adlei Stevenson, speech to the UN, 9 July 1965 in Roland Wilson and Rahill (eds), Adlai Stevenson of the United Nations (1965), 224.

[149] Speech for Make Poverty History Campaign, 3 February 2005, downloaded from <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/politics/4232603.stm> (emphasis added).

2 Comments

Stephen Stillwell

Oh, and global economic enfranchisement is specifically intended to “-disperse sovereignty “in the vertical dimension”.”

Stephen Stillwell

Such a comprehensive work, I’ll need to read it more closely

About this though: “We can observe the necessity, the emergence, the possibility, but beyond that it cannot be explanatory, it must be performative.”

Please imagine this: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:Tralfamadoran777

Specifically, I’m thinking about the possibility of manifesting global economic enfranchisement, extra governmentally, by requiring sovereign debt to be backed with Commons shares, that may be claimed by all adult humans, for deposit in trust with their bank, along with execution of a social contract.

In this way each share holder will receive an equal share of the interest paid on sovereign debt. and an equal structural connection will be established between all global citizens, along with (ideally, potentially) the means to access declared rights.