Australia’s refugee intake at historic lows

Update November 2016: Since this post back in 2015, Australia has announced a special humanitarian intake for Syrian refugees. According to information published by the Department of Border Protection, in the 2015-16 year, 17,555 humanitarian visas were issued including almost 3800 to Syrian refugees. In a discussion paper issued for the 2015-16 year, the Department estimates that the 2019 program will be no less than 18,750 places. Meanwhile the global situation for refugees is no better. Such improvements while welcome are insufficient to the need. Australia cannot solve the problem alone. Yet, it is important to continue to ask if we are doing all we reasonably can and should in these global conditions, as still, the lucky country. Much of what is stated below remains broadly true. Global solutions are clearly necessary – including solving current political dysfunctions between states.[end update]

Update November 2016: Since this post back in 2015, Australia has announced a special humanitarian intake for Syrian refugees. According to information published by the Department of Border Protection, in the 2015-16 year, 17,555 humanitarian visas were issued including almost 3800 to Syrian refugees. In a discussion paper issued for the 2015-16 year, the Department estimates that the 2019 program will be no less than 18,750 places. Meanwhile the global situation for refugees is no better. Such improvements while welcome are insufficient to the need. Australia cannot solve the problem alone. Yet, it is important to continue to ask if we are doing all we reasonably can and should in these global conditions, as still, the lucky country. Much of what is stated below remains broadly true. Global solutions are clearly necessary – including solving current political dysfunctions between states.[end update]

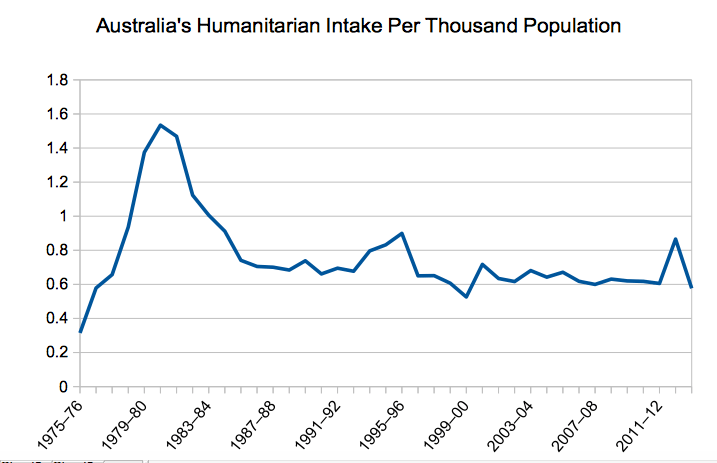

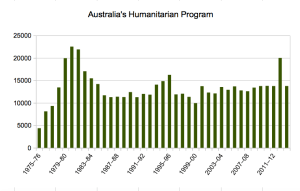

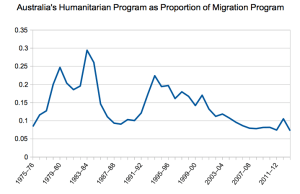

While the world is in crisis, Australia’s refugee intake stands at historic lows. In terms of per capita intake, and in terms of Australia’s overall migration program, Australia’s humanitarian program has declined systematically since the 1970’s. In absolute terms, Australia’s current humanitarian program compares poorly with Australia’s response during other points of global crisis – for example during the Vietnam War.

Recently a conversation has started suggesting that Australia may soon increase its refugee intake. Most immediately the tragedy of Syria and Syrian refugees streaming into Europe has prompted this conversation.

More broadly, there is a world crisis that has displaced more people since the Second World War. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees the number of refugees and displaced worldwide has been higher than ever before at 59,500,000.[1] Most of this displacement is due to war, conflict and persecution. For the first time, the numbers have topped the displacement of World War II. Half of these refugees are children. This crisis has built over the last decade and shows no signs of abating.

Australia’s official program is sometimes compared with official programs of other countries. This ignores that most refugee intakes arise for neighbouring countries which accept their international obligations not to turn refugees away. Thus the highest intakes per capita are Lebanon, hosting 232 refugees per 1000 of population, Jordan 87, Nauru 39, Chad 34, Djibouti 23, South Sudan 21, Mauritania 19, Sweden 15, Malta 14.[1, pp 15] These are numbers that dwarf Australia’s current official program. Interestingly Nauru appears in these figures – a statistical aberration as a result of Australia’s export of refugee flows to Nauru. On UNHCR figures, Australia hosts 2.4 refugees and displaced people per thousand. i.e. currently much less than these other countries. Of course Australia is in a far better position to manage refugee flows than less financially well off countries. These figures are also problematic however, as over time, refugees become long term residents.

Since World War 2, 800,000 refugees and displaced people have been settled in Australia.[2] Two conclusions can be drawn from these figures.

- over time Australia has made a significant contribution to resettling refugees and displaced people – Australia has a long-standing tradition of settling refugees

- currently Australia is low in the league table of countries receiving refugees and displaced people

Another way of assessing Australia’s current contribution is to compare Australia to itself.

From this viewpoint Australia’s refugee intake is at a historic low.

- per capita Australian resettlement has declined systematically for decades

- as a proportion of Australia’s migration program Australia’s refugee resettlement has declined systematically

- in total numbers Australia’s current refugee intake is low as compared with Australia’s intake at other times of global crisis, and has not increased to keep up with these changes.

Except for 1999-2000, on a per capita basis. Australia’s humanitarian program is lower than at any time since 1977 – i.e. we have to go back almost 40 years to find a time when Australia’s per capita contribution was systematically lower than it is today.

As a proportion of the migration program it is the same picture, with peaks in the 1970’s and the 1990’s. Again the proportion is lower than anytime since the 1970’s.

Both per capita comparisons and proportion of the migration program are appropriate bases on which to consider Australia’s current contribution. Both measures implicitly take account of Australia’s capacity to manage increased refugee flows.

If Australia were to do as much as it has done in the past it would double or treble its current humanitarian intake.

Such figures would, based on Australia’s historical contribution, be entirely manageable for Australia. It would not however be sufficient given the global crisis.

The overall global crisis undoubtedly requires a global response, both to address the underlying causes of global conflict and to fix a global refugee system that many now recognise is broken. Europeans, for example, are recognising the necessity of cooperation in face of this global crisis.

Notes:

Annual figures compare financial years for refugee flows with calendar years for population growth. Humanitarian and migration program statistics sourced from the Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection.[3]