Bartolome de las Casas: An early human rights worker

Bartolome de las Casas is one of those remarkable people in history who arose at the very beginning of the modern human rights movement. A great humanitarian; he learnt human rights in his encounter with the people of Central and South America during the sixteenth century European invasion of the Americas. He used his office as Dominican friar and later Bishop to uphold the human rights of the indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Las Casas came to the America’s as part of the colonial expeditions from Spain, arriving in 1502 in Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic), at the very beginning of the encounter between the Europeans and the people of the Americas.

Unlike the great bulk of his contemporaries Las Casas very early reaches the conclusion that nothing can justify what the Spaniards are doing in the Americas. He was influenced by a group of Dominican preachers led by Antonio de Montesinos who in 1511 put the issues squarely before the Spaniards:

Tell me by what right of justice do you hold these Indians in such a cruel and horrible servitude? On what authority have you waged such detestable wars against these people who dealt quietly and peacefully on their own lands? Wars in which you have destroyed such an infinite number of them by homicides and slaughters never heard of before. Why do you keep them so oppressed and exhausted, without giving them enough to eat or curing them of the sicknesses they incur from the excessive labor you give them, and they die, or rather you kill them, in order to extract and acquire gold every day?

The colonists, rejecting these arguments had the preachers recalled to Spain. Las Casas himself became a Dominican and in 1513 accompanied a military campaign against Cuba where he personally witnessed atrocities and, as a colonist, was awarded the usual plot of land and slaves with his friend Pablo de Renteria under the encomienda system which applied to all colonists. In 1514 when reading a passage from Ecclesiasticus he concluded that both slavery and the conquests were wrong. He and his friend, who had reached the same conclusion, freed their slaves and sold their plot of land and Las Casas returned to Spain to appeal to the King to end the abuses.

This was the beginning of a life-long human rights campaign against the colonial abuses. To understand Las Casas’ journey, it is useful to attempt to see the issues through his own eyes. In order to present evidence to the King and others he records what was happening in the Americas painful detail. The following provides some extracts from his work A Brief Report on the Destruction of the Indes:

… driving the Christians from their country. They took up their weapons, which are poor enough and little fitted for attack, being of little force and not even good for defence; For this reason, all their wars are little more than games with sticks, such as children play in our countries.

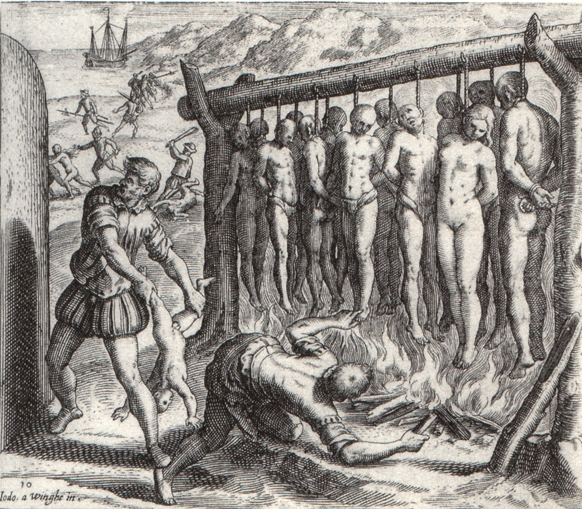

The Christians, with their horses and swords and lances,began to slaughter and practise strange cruelty among them. They penetrated into the country and spared neither children nor the aged, nor pregnant women, nor those in child labour, all of whom they ran through the body and lacerated, as though they were assaulting so many lambs herded in their sheepfold.

They made bets as to who would slit a man in two, or cut off his head at one blow: or they opened up his bowels. They tore the babes from their mothers’ breast by the feet, and dashed their heads against the rocks. Others they seized by the shoulders and threw into the rivers, laughing and joking, and when they fell into the water they exclaimed: “boil body of so and so!” They spitted the bodies of other babes, together with their mothers and all who were before them, on their swords.

They made a gallows just high enough for the feet to nearly touch the ground, and by thirteens, in honour and reverence of our Redeemer and the twelve Apostles, they put wood underneath and, with fire, they burned the Indians alive.

They wrapped the bodies of others entirely in dry straw, binding them in it and setting fire to it; and so they burned them. They cut off the hands of all they wished to take alive, made them carry them fastened on to them, and said: “Go and carry letters”: that is; take the news to those who have fled to the mountains.

They generally killed the lords and nobles in the following way. They made wooden gridirons of stakes, bound them upon them, and made a slow fire beneath: thus the victims gave up the spirit by degrees, emitting cries of despair in their torture.

I once saw that they had four or five of the chief lords stretched on the gridirons to burn them, and I think also there were two or three pairs of gridirons, where they were burning others; and because they cried aloud and annoyed the captain or prevented him sleeping, he commanded that they should strangle them: the officer who was burning them was worse than a hangman and did not wish to suffocate them, but with his own hands he gagged them, so that they should not make themselves heard, and he stirred up the fire, until they roasted slowly, according to his pleasure. I know his name, and knew also his relations in Seville. I saw all the above things and numberless others.

We might be minded to disbelieve such obscene inhumanity but for the fact that modern history has been punctuated with just such genocides. In writing out these accounts to the King, La Casas says:

“So as not to keep criminal silence concerning the ruin of numberless souls and bodies that these persons cause, I have decided to print some, though very few, of the innumerable instances I have collected in the past and can relate with truth, in order that Your Highness may read them ….”

What Las Casas does is what human rights workers have done ever since: collect evidence of human rights abuses and draw them to the attention of those in authority so as to bring them to an end. What he records is the beginning of what is best described as an Apocalypse that was to engulf the cities, towns and villages of the Americas. Horrifically, that colonial process by which Europeans subjugated most of the world, was to continue for 400 years sweeping across the world killing and violating the rights of hundreds of millions of human beings. Las Casas makes its character clear to us.

We give as a real and true reckoning, that in the said forty years, more than twelve million persons, men, and women, and children, have perished unjustly and through tyranny, by the infernal deeds and tyranny of the Christians; and I truly believe, nor think I am deceived, that it is more than fifteen.

Two ordinary and principal methods have the self-styled Christians, who have gone there, employed in extirpating these miserable nations and removing them from the face of the earth. The one, by unjust, cruel and tyrannous wars. The other, by slaying all those, who might aspire to, or sigh for, or think of liberty, or to escape from the torments that they suffer, such as all the native Lords, and adult men; for generally, they leave none alive in the wars, except the young men and the women, whom they oppress with the hardest, most horrible, and roughest servitude, to which either man or beast, can ever be put. To these two ways of infernal tyranny, all the many and divers other ways, which are numberless, of exterminating these people, are reduced,resolved, or sub-ordered according to kind.

The reason why the Christians have killed and destroyed such infinite numbers of souls, is solely because they have made gold their ultimate aim, seeking to load themselves with riches in the shortest time and to mount by high steps, disproportioned to their condition: namely by their insatiable avarice and ambition, the greatest, that could be on the earth. These lands, being so happy and so rich, and the people so humble, so patient, and so easily subjugated, they have had no more respect, nor consideration nor have they taken more account of them (I speak with truth of what I have seen during all the aforementioned time) than,—I will not say of animals, for would to God they had considered and treated them as animals,—but as even less than the dung in the streets.

Having set out a general description of the oppression the Spaniards were visiting on the Indians, Las Casas then details case after case where such methods were used, tracing the invasions from the Caribbean, to Mexico, Central America and Peru. In every part of the Americas that the Spaniards reached they would violently subjugate the people, generally committing brutal and genocidal massacres, extracting tributes of gold and then reducing what remained of the the population to slavery. The Indians were brutally used for the financial gain, for sport, as tools in the oppression of other Indian populations, as pack animals and even as food for the Spaniards’ dogs.

Las Casas did all he could not only to expose these abuses but to change the situation. He travelled to Spain to appeal to the King. In 1542 his efforts resulted in the New Laws which were designed to protect the Indians. Although the laws were flouted by the colonists, they sought to bring to an end the encomiendas system, which were so oppressive to the Indians. Las Casas famously debated both the injustice of the forceable conquest of the Indes and the enslavement of the Indians before the Spanish Court as being contrary both to divine and Spanish law. As Bishop of Chiapas in Central America, he denied his European parishioners absolution if they kept slaves. His long life was devoted to ameliorating and ending the human rights abuses he saw. His life has repeatedly drawn fruit, in the eighteenth century abolitionists recalled his work, in the nineteenth century South American liberation movements used his name, and his name is associated with Liberation Theology in the 20th century and the Latin American tradition of human rights in the 21st. It is also, perhaps, no coincidence, that the countries of South America where indigenous populations and cultures have best survived, are among those countries where Las Casas worked and focussed his attention.

Viggo Mortensen reads Bartolome de Las Casas, “The Devastation of the Indies: A Brief Account” (1542) in Spanish and English from Voices of a People’s History (English starts at 5:15).

The meeting between the Europeans and the peoples of the Americas in the sixteenth century raised a central issue: what was the relationship between these two groups of people? There was no history which could be offered to justify oppression. Accordingly, its injustice was clear. Yet, as we have seen above, the Spaniards largely resolved this new relationship in terms of brutality, exploitation and subjugation. Las Casas saw things differently:

All the races of the world are men, and of all men and of each individual there is but one definition, and this is that they are rational. All have understanding and will and free choice, as all are made in the image and likeness of God … Thus the entire human race is one.

Like the later abolitionists of the eighteenth century who took as their slogan ‘Am I not a man, and a brother?” in their efforts to abolish the Atlantic slave trade, Las Casas upholds human equality and human fraternity. These ideas were to appear in the rights declarations of the enlightenment and in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights are expressed as follows:

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Las Casas saw this hundreds of years before it was universally acknowledged. In part, his insight comes from the scholarly and religious traditions from which he comes, but just as surely it was realized in the experience of witnessing human rights abuses and in the faces, lives and dignity of the Indians who he met, whom he repeatedly extolled and who helped him see how those traditions led to this answer. He was deeply ashamed of the conduct of his countrymen who called themselves “Christian” but he held in high regard the civilised conduct of Indians who the Spaniards so cruelly oppressed.

The question “are we one people with equal rights?” is still before us today. It is the central question which arises in the discrimination inflicted on non-citizens. Are non-citizens to be treated as lesser human beings – driven them from communities where they are said not to belong; imprisoned; vilified by the media; exploited to advance the careers of politicians; solely valued when in their home countries for the delivery of goods such as chocolate, coffee and textiles; denied access if they are poor, but admitted if it suits a state’s immigration needs, or the need for workers to do the menial jobs which the native population does not want to undertake?

Or is this entire model profoundly immoral and unacceptable?

It ought not escape our notice, that in many cases the denial of equal treatment and access, is made by the places where those who benefitted from the processes of colonization reside: places such as Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia and that those excluded are, in large measure, the descendants of the populations oppressed during colonial days.

Sources:

Bartholomew de Las Casas; his life, apostolate,and writings By Francis Augustus MacNutt Cleveland, U.S.A. The Arthur H. Clark Company 1909

From Conquest to Constitutions: Retrieving a Latin American Tradition of the Idea of Human Rights Paolo G. Carozza Human Rights Quarterly 25 (2003) 281–313

Bartolome de Las Casas: Witness: Writing of Bartolome de Las casas. ed and trans by George Sanderlin (Maryknoll: Orbis books, 1993) 66-67

Images:

Wikipedia Creative Commons

“http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Chichicastenango-004.jpg”

“http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Qichwa_conchucos_01.jpg”

“http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:De_Bry_1c.JPG”