The Kitab-i-Aqdas: A New Paradigm

The term “paradigm” is used in a way now familiar in everyday speech – such as in the phrase “a new paradigm” or “paradigm shift”. But this kind of usage has a particular and recent origin. It comes from a philosopher of science whose name was Thomas Kuhn. In the late 20th century, this philosopher undertook a systematic study of the history of science and it how progresses. What he persuasively showed was that science from time to time undergoes “scientific revolutions” — it enters a new paradigm or undergoes a paradigm shift.

The term “paradigm” is used in a way now familiar in everyday speech – such as in the phrase “a new paradigm” or “paradigm shift”. But this kind of usage has a particular and recent origin. It comes from a philosopher of science whose name was Thomas Kuhn. In the late 20th century, this philosopher undertook a systematic study of the history of science and it how progresses. What he persuasively showed was that science from time to time undergoes “scientific revolutions” — it enters a new paradigm or undergoes a paradigm shift.

Such revolutions arise when an existing scientific paradigm encounters more and more unanswered questions that it is unable to deal with. At first, a small number of new thinkers propose entirely different ways of solving these problems – and more traditional thinkers will vociferously oppose change. Through processes that involve community as well as theory and experiment, eventually, one of these new ways of thinking may become a new paradigm. Scientists will switch from the old paradigm – no longer defending it — but devoting themselves to exploring and drawing insights from the new paradigm. We may, for example, think of the shift from Ptolemaic to Copernican astronomy or from Newtonian science to Relativity theory. A critical feature of the shift is that the new and old paradigms are “incommensurable”. That is, we cannot use the new paradigm as a measure of the old one and vice versa. Within its own limits, each scientific paradigm is “correct” and it provides its own criteria for measurement.

Bahá’u’lláh’s discussion of “seven heavens” and “extrasolar planets” provides a beautiful example. Both ways of thinking of the heavens are drawn from humanity’s history of science — yet the two ways of understanding the world cannot be used as a measure of each other. One must simply think about reality in a different way to understand each way of thought.

In the Kitab-i-Aqdas Bahá’u’lláh describes his teachings essentially in terms of a “new paradigm”.

O leaders of religion! Weigh not the Book of God with such standards and sciences as are current amongst you, for the Book itself is the unerring Balance established amongst men. In this most perfect Balance whatsoever the peoples and kindreds of the earth possess must be weighed, while the measure of its weight should be tested according to its own standard, did ye but know it.[1]

This is the infallible Balance which the Hand of God is holding, in which all who are in the heavens and all who are on the earth are weighed, and their fate determined, if ye be of them that believe and recognize this truth.[2]

It is easy to unconsciously bring our own culture, assumptions and prejudices to a reading of Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings. Or we might have our own lens through which we try to “measure” his teachings. This is essentially incoherent – because such approaches often seek to apply the measure of historical paradigms, which, as in the case of scientific paradigms are “incommensurable” with each other. As Bahá’u’lláh observes later in his teachings:

… it is true to say that they object to that which they comprehend, not to the expositions given by the Expounder, nor the truths imparted by the One true God, the Knower of things unseen. Their objections, one and all, turn upon themselves, ….[3]

In drawing on the history of science, it is not intended to suggest that science and religion are the same. Science, for example, is (primarily) concerned with “reading” the “book of creation”, while religion is concerned (primarily) concerned with reading the “book of revelation”. Nonetheless, we may observe that as bodies of knowledge they share in common the phenomenon of periodic paradigm shifts.

Selected references:

Allan Chalmers, What is this Thing Called Science?

Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

(This article is the 150th in a series of what I hope will be 200 articles in 200 days for the 200th anniversary of the birth of Bahá’u’lláh. The anniversary is being celebrated around the world on 21 and 22 October 2017, The articles are simply my personal reflections on Bahá’u’lláh’s life and work. Any errors or inadequacies in these articles are solely my responsibility.)

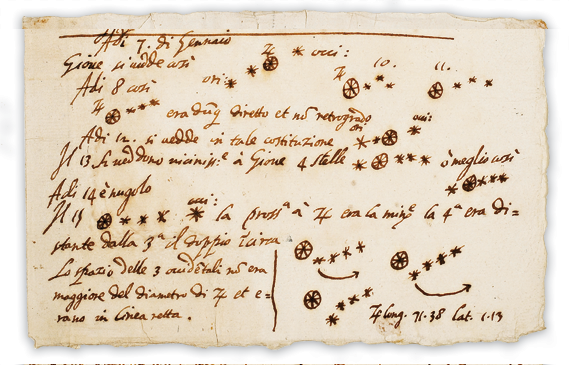

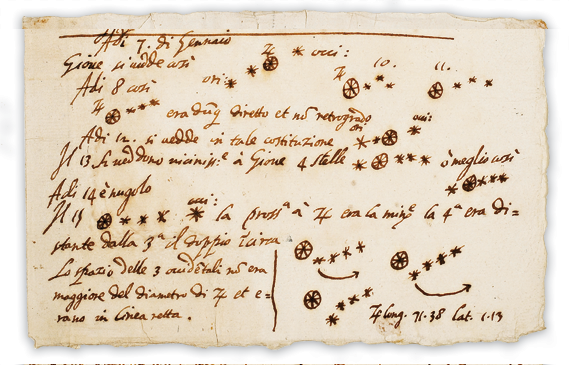

Image: Part of ‘an image of a draft letter written by Galileo Galilei in August 1609 to Leonardo Donato, Doge of Venice, and currently held in the University of Michigan Harlan Hatcher Graduate Library’s Special Collections. The University of Michigan says the following about its history: “In 1609 [Galileo] received a description of a telescope which had been developed the year before in the Dutch town of Middelburg by an optician, … this sheet shows the use to which Galileo put this optical device: as he viewed the skies on successive evenings in January, 1610, he noted his first observations of the planet Jupiter and four of Jupiter’s moons.” Galileo’s observations contributed to a paradigm shift away from Ptolemaic astronomy. Wikimedia commons