Extremes of Wealth and Poverty

The increasing gulf between rich and poor has recently re-emerged as an issue in public debate, both as an issue of economic justice and as an issue contributing to political instability in the world.[1]

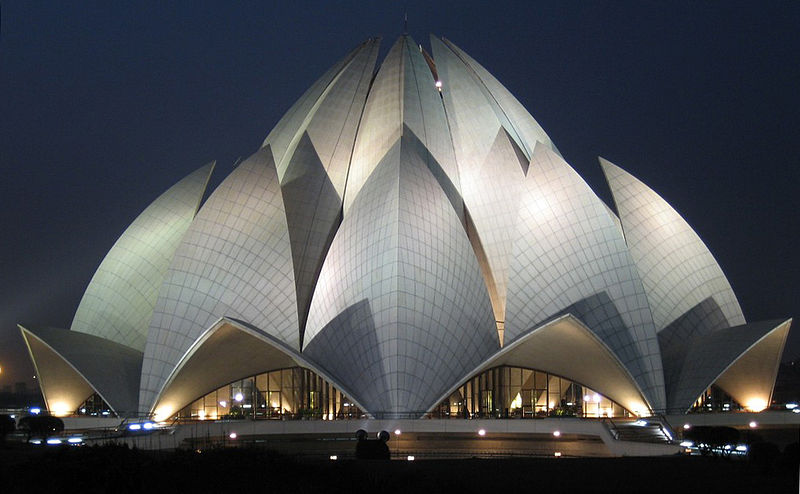

The issue has been a standing concern of the Baha’i community.

In his early mystical writings Bahá’u’lláh draws attention to the injustice of disparities of wealth and poverty. Bahá’u’lláh challenges the common societal devaluation of the poor (and assumptions about a worthy human life):

Vaunt not thyself over the poor, for I lead him on his way and behold thee in thy evil plight and confound thee forevermore.[1]

This is not enough. The wealthy have obligations of generosity in respect of the use of wealth.

O YE RICH ONES ON EARTH!

The poor in your midst are My trust; guard ye My trust, and be not intent only on your own ease.[2]

Bestow My wealth upon My poor, that in heaven thou mayest draw from stores of unfading splendor and treasures of imperishable glory.[3]

Extremes of wealth and poverty is one of the issues to which ‘Abdu’l-Bahá drew attention in his visit to the West:

Each one of you must have great consideration for the poor and render them assistance. Organize in an effort to help them and prevent increase of poverty. The greatest means for prevention is that whereby the laws of the community will be so framed and enacted that it will not be possible for a few to be millionaires and many destitute. One of Bahá’u’lláh’s teachings is the adjustment of means of livelihood in human society. Under this adjustment there can be no extremes in human conditions as regards wealth and sustenance.[4]

A financier with colossal wealth should not exist whilst near him is a poor man in dire necessity. When we see poverty allowed to reach a condition of starvation it is a sure sign that somewhere we shall find tyranny. Men must bestir themselves in this matter, and no longer delay in altering conditions which bring the misery of grinding poverty to a very large number of the people. The rich must give of their abundance, they must soften their hearts and cultivate a compassionate intelligence, taking thought for those sad ones who are suffering from lack of the very necessities of life.

There must be special laws made, dealing with these extremes of riches and of want.[5]

Nonetheless ‘Abdu’l-Bahá regards absolute economic equality as impossible to achieve. The failed 20th century experiments in this direction amply support this conclusion.

Most recently the Universal House of Justice, the international governing body of the Baha’i Faith, wrote to Baha’is around the world, drawing attention to this concern and the implications for economic life of the individual and community action. In part, its letter observes:

The welfare of any segment of humanity is inextricably bound up with the welfare of the whole. Humanity’s collective life suffers when any one group thinks of its own well-being in isolation from that of its neighbours or pursues economic gain without regard for how the natural environment, which provides sustenance for all, is affected. A stubborn obstruction, then, stands in the way of meaningful social progress: time and again, avarice and self-interest prevail at the expense of the common good. Unconscionable quantities of wealth are being amassed, and the instability this creates is made worse by how income and opportunity are spread so unevenly both between nations and within nations…. [T]here is an inherent moral dimension to the generation, distribution, and utilization of wealth and resources.[5]

The letter continues to an investigation of what it implies for the individual, the community and institutions (but especially the individual).

Every choice a Baha’i makes – as employee or employer, producer or consumer, borrower or lender, benefactor or beneficiary – leaves a trace, and the moral duty to lead a coherent life demands that one’s economic decisions be in accordance with lofty ideals, that the purity of one’s aims be matched by the purity of one’s actions to fulfil those aims.[6]

While individuals alone cannot change economic circumstances without the complementary and supportive frameworks of community and institutions, there is clearly a power in individual decision and action. How can our individual choices contribute to a more just economic order?

This article is the 28th in a series of what I hope will become 200 articles in 200 days for the 200th anniversary of the birth of Bahá’u’lláh. The anniversary is being celebrated around the world on 21 and 22 October 2017. The articles are simply my personal reflections on Bahá’u’lláh’s life and work. Any errors or inadequacies in these articles are solely my responsibility.