Three reasons for Abandoning Mandatory Detention

A paper delivered at a roundtable on alternatives to detention held in Canberra, June 9 – 10, 2011

By Penelope Mathew

Freilich Foundation Professor

The Australian National University

Why does mandatory detention of asylum seekers continue in Australia when there are alternatives? In this short presentation, I invite people to think about three important issues that shape the debate about Australia’s policy of mandatory detention – legality, proportionality and risk.

I begin with legality, because it is clear that one of the obstacles to alternatives to detention is the perception that unauthorized arrivals seeking asylum have acted illegally. One reason for this perception is that human rights law speaks with a muted voice on the process of migration to secure protection. Human rights law is primarily directed to what we might call ‘in country’ protection, while the Refugee Convention only comes into play when a person has already left their country of origin. By definition, a refugee is a person outside the country of origin, so migration is an inherent part of the asylum process, yet, the Refugee Convention does not expressly grant the right to enter a foreign country. The migratory component of protection is obscured.

If we conceptualize the refugee definition as implicitly requiring that a refugee cross a border, it is readily apparent that to require that a person migrate in order to seek protection, but then to illegalize or criminalize the process of migration would be to set up an unbearable contradiction. It would be the sort of contradiction encountered by the House of Lords in the Pinochet case. There the judges had to consider whether to recognize immunity for Chile’s former head of state, Augusto Pinochet, in spite of the requirement in the Convention against Torture to punish acts of torture, an act which, as defined in that Convention, requires official participation. Pinochet was the person most responsible for acts of torture committed by his regime, yet the customary doctrine of immunity might serve to grant effective impunity for his actions. The House of Lords decided that immunity would not apply to a former head of state accused of torture.

Similarly (or perhaps conversely) asylum seeking cannot be criminalized, nor should international law merely tolerate it. As the excellent paper prepared for UNHCR, Back to Basics, states, to seek asylum is a lawful act. (Alice Edwards, Back to Basics: The Right to Liberty and Security of Person and ‘Alternatives to Detention’ of Refugees, Asylum-Seekers, Stateless Persons and Other Migrants, UNHCR, April 2011.) This is true even if it is pursued by means that may involve the technical breach of domestic immigration law and even if it involves the use of services that have been criminalized by the international community.

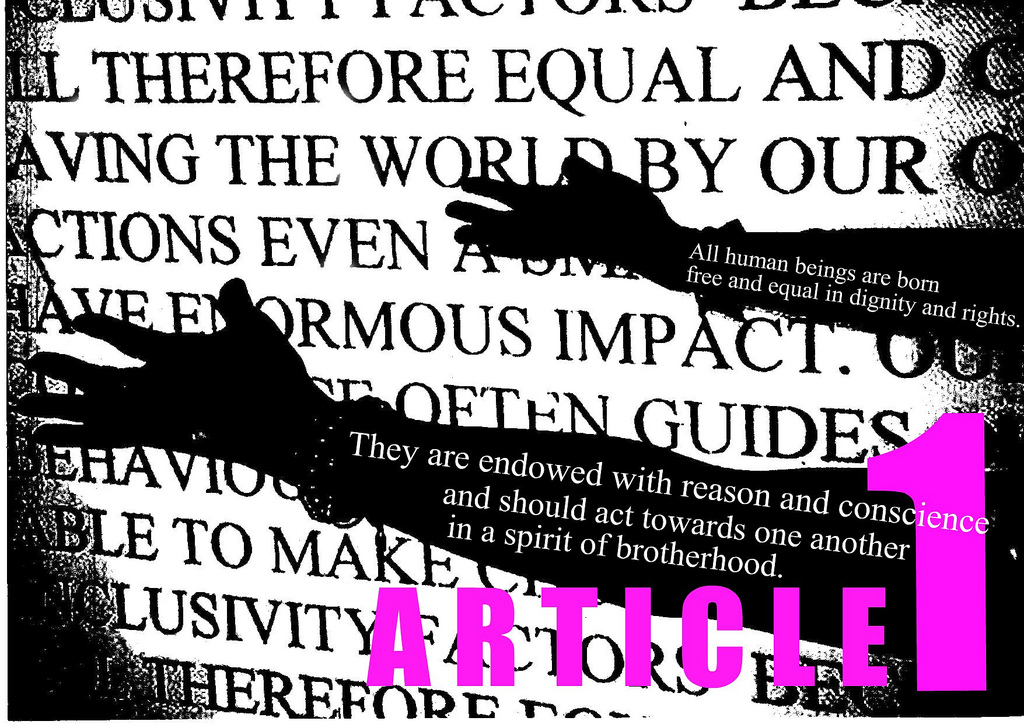

This reading of international law is confirmed by several international instruments. To begin with, Article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights protects the right to seek asylum. Although formally non-binding, this document now provides one basis for Universal Periodic Review by the UN Human Rights Council – a process that covers every UN member state. The provision against penalties for unlawful entry in Article 31 of the Refugee Convention also tells us that entry in contravention of domestic immigration laws must not be penalized and that only necessary restrictions on movement may be imposed in such cases. It does contain some limitations – asylum seekers must have come ‘directly’ from a place of persecution and ‘show good cause’ for their irregular means of entry. However, when we consider the UNHCR map of parties to the Convention and the red zone of countries between refugee-generating countries and Australia in which so few countries are party to the Convention, it is relatively easy to present the case that unauthorized arrivals seeking asylum in Australia should not be penalized. (See http://www.unhcr.org/3ddcb8a34.html.) Finally, the UN Protocol on Migrant Smuggling provides that smuggled migrants are not to be prosecuted for being smuggled (Article 5) and that the Refugee Convention’s protections remain in place (Article 19).

While on the subject of people smuggling, I want to comment briefly on the refugee swap with Malaysia. I think we ought to be clear about what Australia is doing. On the basis that we don’t want to see ship wrecks off our shores, we will attempt to ensure that refugees remain in precarious situations in their countries of origin or transit countries, or that they crash elsewhere. A swap involving 800 out of the global population of millions of refugees is not going to break the people smugglers’ ‘business model’ (even if one could assume that there is a ‘people smugglers central’ with a coordinated strategic plan). Boats and lorries of migrants and refugees will still undertake dangerous journeys, but we hope journeys to Australia will not continue. And we are prepared to test our hypotheses by using the 800 as guinea pigs on the basis of paper guarantees from a country that does not have a track record of adequate protection of refugees. While refugee lawyers have had to concede that states will attempt to share (though in some cases a better descriptor is ‘shift’) responsibility for refugees among themselves, such arrangements should be premised on confidence that refugees will be protected in places to which they will be sent. In the case of Malaysia, we are trying, in the face of evidence to the contrary, to generate the necessary confidence that the 800 will be safe through governmental assurances.

Having established that seeking asylum is a lawful act, some might object that not all asylum seekers are refugees. While international law holds that recognition of refugee status through national procedures is merely declaratory, there are some asylum seekers who do not in fact meet the definition of a refugee. They may genuinely claim asylum, wrongly believing that they are entitled to the grant of asylum. At the other end of the spectrum, states fear that the asylum process is abused by those who know they don’t have a claim – a fear that may be bolstered by a number of claims which do not appear credible. This fear may contribute to the interception and containment strategies adopted by states, including detention. This is where the second concept I want to address – proportionality – comes into play.

The fundamental principle of proportionality that enters the equation every time a human right is subjected to limitations requires that the actions of a few cannot dictate what happens to those with genuine claims. Detention that does not respect the principle of proportionality will be arbitrary, and this has been confirmed every time the UN Human Rights Committee has had occasion to look at Australia’s policy of mandatory detention. Australia’s policy of mandatory detention has been the context for numerous communications before the United Nations Human Rights Committee. The first of these, A v Australia, concerned a Cambodian man held in detention for four years as he negotiated the asylum system. Mr A was eventually permitted to stay in Australia. The crucial passage of the Committee’s views is as follows:

the Committee recalls that the notion of “arbitrariness” must not be equated with “against the law” but be interpreted more broadly to include such elements as inappropriateness and injustice. Furthermore, remand in custody could be considered arbitrary if it is not necessary in all the circumstances of the case, for example to prevent flight or interference with evidence: the element of proportionality becomes relevant in this context. The State party however, seeks to justify the author’s detention by the fact that he entered Australia unlawfully and by the perceived incentive for the applicant to abscond if left in liberty. The question for the Committee is whether these grounds are sufficient to justify indefinite and prolonged detention.

The Committee agrees that there is no basis for the author’s claim that it is per se arbitrary to detain individuals requesting asylum. Nor can it find any support for the contention that there is a rule of customary international law which would render all such detention arbitrary.

The Committee observes however, that every decision to keep a person in detention should be open to review periodically so that the grounds justifying the detention can be assessed. In any event, detention should not continue beyond the period for which the State can provide appropriate justification. For example, the fact of illegal entry may indicate a need for investigation and there may be other factors particular to the individuals, such as the likelihood of absconding and lack of cooperation, which may justify detention for a period. Without such factors detention may be considered arbitrary, even if entry was illegal. In the instant case, the State party has not advanced any grounds particular to the author’s case, which would justify his continued detention for a period of four years, during which he was shifted around between different detention centres. The Committee therefore concludes that the author’s detention for a period of over four years was arbitrary within the meaning of article 9, paragraph 1. (A v Australia, paras 9.2 – 9.4).

In a recent statement to the UN Human Rights Council following the visit of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, the Australian government defended the mandatory detention policy as follows:

In Australia, mandatory detention is based on a person’s unauthorised arrival, not on seeking asylum. Of the current caseload of approximately 15,300 asylum seekers whose status is yet to be determined, more than 70 percent remain in the community. The length and conditions of detention are subject to constant and regular review. The UN Human Rights Committee’s Final Views in A v Australia (Communication No 560/1993) states – and I quote – “there [is] no basis for the claim that it is per se arbitrary to detain individuals requesting asylum … nor [is] there a rule of customary international law which would render all such detention arbitrary”.

Similar statements have been made in Australia’s official response to the process of Universal Periodic Review.

These statements suggest that a mandatory detention policy for unauthorized arrivals is not arbitrary per se, and that the introduction of review by the Department of Immigration and the Commonwealth Ombudsman has been sufficient to deal with the concerns of the Committee about indefinite or prolonged detention. However, Article 9(4) of the ICCPR provides for review of the legality of detention by a court, and the Committee has interpreted that to mean review as a check on arbitrary detention in the international legal sense. Any person who seeks review by the Australian judiciary will come up against sections 189 and 196 of the Migration Act which provide that unlawful citizens within or seeking to enter the migration zone must be detained until deported, removed or granted a visa. Review in these circumstances is meaningless because the Court is only empowered to confirm that an unauthorized arrival is being detained under domestic law. Meaningful review requires a basis upon which the courts may order release from detention for any particular individual. This Australia does not have.

What we do have are various exceptions to mandatory detention. In theory, the exceptions to mandatory detention have expanded over time. They involve bridging visas, which are available on the basis of very limited criteria to unauthorized arrivals, and the power to determine on the basis of the public interest that an unauthorized arrival may reside in a place other than immigration detention (‘community detention’).

In practice, the available exceptions to detention have been sidelined or underutilized in the case of irregular maritime arrivals or boat people. From 2001 to 2007, the Pacific Solution ensured that boat arrivals were taken to the offshore detention centres on Nauru or Papua New Guinea. It appears that once again, Australia is contemplating detention elsewhere. This is not an alternative to detention, and it is clear that Australia retains responsibility for the detention as a matter of international law.

At present, irregular maritime arrivals or boat people may only avail themselves of exceptions to mandatory detention through the exercise of the Minister’s personal and non-compellable discretion. Following the closure of the detention centres on Nauru and Papua New Guinea, ‘boat people’ are still detained as ‘offshore entry persons’, meaning that they cannot apply for any visa, including a bridging visa, unless the Minister lifts the bar on a visa application. Community detention has also been underutilized, attracting consistent criticism by the Australian Human Rights Commission.

It is therefore questionable whether these exceptions have delivered sufficient changes to the basic mandatory detention regime to justify the conclusion that Australia is compliant with Article 9(1); it is clear that Australia does not comply with Article 9(4); and the two are necessarily related. It is fundamental to the rule of law that in order to secure liberty, there must be adequate, judicial controls of executive power, and this proposition has clearly informed the Human Rights Committee’s reading of Article 9.

Australia’s statements to the UN place far too much emphasis on the statement in A v Australia that detention of asylum seekers is not arbitrary per se. Of course it may be possible to detain an asylum seeker initially if they arrive without a visa: in the Bakhtiyari case, the initial period of detention was not found to be arbitrary, only ‘undesirable’. As acknowledged in A v Australia, there may be a need to investigate the circumstances. Further, as the Committee goes on to say in A v Australia, if there are circumstances particular to the individual, such as likelihood of absconding, then detention can be justified. As detention continues, the requirement of providing a justification becomes even stronger.

Some might complain that the Committee does not explain at what point detention might become arbitrary if the initial detention is permissible. However, it is up to us, Australia, to offer proper justification up front for the detention of any particular individual. It is also clear from subsequent decisions, beginning with C v Australia that we are required to consider whether there are less restrictive means of achieving our aims. In C v Australia, for example, the Committee expressly mentioned reporting obligations, sureties or other conditions. In fact, alternatives to detention can and should be considered at the point of arrival, not just after detention has commenced.

So what are the reasons for maintaining what is in essence the same mandatory detention policy, which inevitably results in detention of ‘boat people’, that has been in place since 1992? I’m going to nominate two. First, since the 1990s, to varying degrees, Australian governments have wanted to appear tough on boat arrivals. The exception is the Rudd government which took a more humane approach, announcing new detention values, and placing legislation before the parliament. Second, it seems that Australian governments have been incredibly risk averse. So let’s turn, finally, to talk about risk.

The figures from the examples of release programs cited in Back to Basics suggest the risk of absconding is far less than 10 per cent. It is disproportionate to forbid the exercise of a fundamental right, liberty, in 100 percent of cases on the basis of a less than 10 percent risk of absconding. This is particularly true in the context of Australian boat arrivals where the acceptance rate regarding refugee status is extremely high.

To quote the well-worn epithet that applies in the criminal justice context, it is better to let nine guilty men go than to convict one innocent man. Citizens accused of crimes may be bailed into the community and this is governed by a legislative framework and supervised by the judiciary. Yet this presumption of liberty is denied to persons who eight or nine times out of ten prove to have genuinely pursued a lawful activity – the act of seeking asylum. In the statement to the UN Human Rights Council, Australia indignantly protests that Australia’s immigration laws are facially neutral and not racially discriminatory. However, when we look at rates of absconding presented in the research and compare the treatment of asylum seekers with citizens accused of crimes, it is very difficult to differentiate the risk aversion regarding asylum seekers from xenophobia. I hope that the work of UNHCR and the International Detention Coalition (International Detention Coalition, There are Alternatives: a Handbook for Preventing Unnecessary Immigration Detention (2011)) can persuade us to ‘move forward’ and implement alternatives to detention in legislation with proper judicial scrutiny just as we do with citizens, thereby demonstrating that we do value all human beings equally.

_____________________________________________________

Image Source: Creative Commons http://www.flickr.com/photos/diacimages/5424306236/